by Kristina Bryant and Tara Kunkel

Vol. 106 No. 1 (2022) | Necessarily Engaged | Download PDF Version of Article

Beginning in March 2020, courts transformed how they conduct business by rapidly transitioning to online platforms. Moving business entirely online required courts to train judges, court staff, prosecutors, lawyers, and litigants; establish new policies and protocols; and purchase and issue new equipment and software licenses — all in a very short period of time, and often while people were working remotely. But by the summer of 2020, courts throughout the nation were routinely conducting remote hearings, and many courts continued to conduct at least some, if not most, court hearings online well into 2021.

In the spring of 2021, Rulo Strategies, in collaboration with the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) and Wayne State University, initiated a large-scale, national examination of remote court hearings practices in treatment court settings. The research team selected treatment courts for study because they require frequent court hearings. Over 1,350 participants in judicially led diversion programs across 27 states completed the online survey between February 2021 and July 2021. Respondents indicated that about 30 percent of the court hearings they participated in during this time were in-person only; 70 percent included both in-person and remote proceedings. The following is a summary of some of the findings; the full report is available at https://bit.ly/3LW7AHi.

Court users enrolled in treatment courts were asked to rate their agreement with a series of statements about their experiences with in-person court and virtual court. The responses of those who had only experienced virtual court were compared to the group of those respondents who had transitioned from in-person court to virtual court. Options for responses to each statement were 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree), with averages reported for each statement.

Survey responses suggested that remote sessions may be more user-friendly than in-person sessions. Respondents who had transitioned from in-person to virtual hearings rated their comfort level for in-person hearings lower (3.88) than for virtual hearings (4.06). This difference was statistically significant. Respondents who only attended court virtually rated their comfort participating in court sessions highest (4.37). The difference between the virtual-only participants (4.37) and the group that transitioned from in-person to virtual hearings (3.88) was also statistically significant.

Respondents who attended both in-person court and virtual court provided similar responses about their ability to be open and honest with the judge for both settings (in person 4.24 compared to virtual 4.26). Respondents who only attended court virtually rated their ability to be open and honest during virtual hearings higher (4.41). The difference is statistically significant.

Across most measures, court users who only experienced virtual court sessions consistently reported more positive feelings about virtual sessions than those who experienced both in-person and virtual sessions. One interpretation of the results is that the recollection of positive in-person services taints the perception of virtual services. A limitation of our study is its retrospective, cross-sectional nature; in other words, participants answered questions based on their recollections, which may or may not accurately reflect how they felt about in-person services at the time they were delivered.

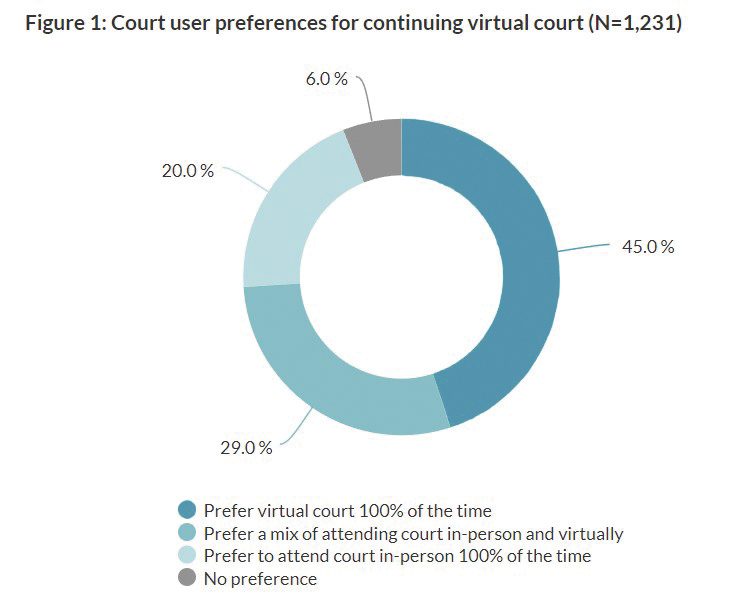

Overall, 45 percent of respondents indicated they would prefer to attend court 100 percent virtually; 29 percent indicated they would prefer a hybrid of in-person and remote court hearings. Just 20 percent said they’d prefer in-person sessions only. (See Figure 1.)

Overall, 45 percent of respondents indicated they would prefer to attend court 100 percent virtually; 29 percent indicated they would prefer a hybrid of in-person and remote court hearings. Just 20 percent said they’d prefer in-person sessions only. (See Figure 1.)

Respondents indicated their top three reasons for preferring remote court hearings were: 1) they were more comfortable talking in a virtual setting; 2) they were less anxious when they attended court remotely; and 3) remote hearings saved them or their loved ones time. Court users who preferred in-person court gave these reasons: 1) they were more comfortable talking in person; 2) they liked seeing their peers in court; and 3) they felt disconnected from the court when they participated remotely.

The research team also conducted a companion survey of more than 850 court professionals and found that court staff, including judges, shared some of the same observations as court users about virtual services in treatment courts but were generally more pessimistic about remote hearings. When researchers asked court professionals about the quality of information when court hearings were offered in person vs. virtually, 83 percent rated the quality of information as “high” when court was held in person, and 52.6 percent rated the quality of information as “high” when court was held virtually. More than half of practitioners, 60 percent, said the quality of information did not change when their court transitioned from in-person to virtual sessions. (Read the full report at https://bit.ly/3rmQDOj.)

Researchers also asked court staff to rate the judge’s ability to form meaningful connections during in-person and virtual sessions. In general, court professionals expressed concern about the judge’s ability to form connections virtually compared to in person: 87 percent of staff respondents rated judges’ ability to form connections with court participants as “high” when court was held in person; just 41.4 percent rated judges “high” on the same metric when court was held virtually.

A common critique of treatment court and other diversion programs is that they are not accessible to everyone who is eligible to participate. Virtual service delivery has the potential to increase the number of individuals eligible to participate in such programs because it may mitigate obstacles that have historically been barriers to participation, such as lack of transportation to court or competing work or family obligations.

To address the assumption that in-person attendance may be a hurdle to treatment court users, the research team asked survey participants about attendance when court hearings were offered in person and virtually. Court professionals indicated that attendance was a little more likely to be “high” when court was held in person (75.7 percent) compared to virtual (72.8 percent).

This is surprising given that the survey was administered at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Court users reported a variety of negative experiences during the pandemic: Nearly half (45.7 percent) had experienced increased mental health symptoms during the pandemic; 42.4 percent lost their job or income; and 11.9 percent reported loss of housing. These experiences can easily become barriers to participating in court when sessions are held in person. One court participant said, “I appreciate all the help. I don’t know how I would have attended all the classes, court appearances, and urinalysis due to gas and living in my car when I lost my apartment if we did not go virtual.”

Other studies have supported the idea that court attendance improves in virtual hearings. In some parts of North Dakota, appearance rates for criminal warrant hearings went from 80 percent before the pandemic to nearly 100 percent. New Jersey reported its failure-to-appear rate in criminal cases dropped from 20 percent to 0.3 percent starting the week of March 16, 2020, when courts there began to conduct virtual hearings. Michigan’s failure-to-appear rate went from 10.7 percent in April 2019 to 0.5 percent in April 2020.

Though the full picture on data for attendance in virtual vs. in-person court proceedings is not yet clear, courts should continue to consider how technology access may inhibit or help participants’ ability to attend virtual proceedings.

Access to broadband internet service has become a vital tool for staying connected in the digital era, particularly in the recent years of the pandemic. Although virtual service delivery has the potential to increase access to court, preliminary survey results from this study suggest some treatment court participants do face technological barriers to access when participating in remote court hearings. For example, 4 percent of court users reported not having reliable wi-fi or internet service to participate in services by video, and 3 percent indicated they lacked the necessary equipment to participate in services by video. Still, these numbers were lower than court practitioners expected and should be considered in the context of the barriers reported for in-person court hearings.

Furthermore, courts are finding creative ways to address these gaps in technology. Some are establishing courthouse “Zoom rooms” — physical rooms in courthouses that are free to use and are outfitted with the equipment needed to participate in online court hearings. Some courthouses also offer free guest wi-fi.

Additional research is needed to determine how litigants in other matters, including civil and criminal cases, prefer to attend court; how virtual hearings impact perceptions of procedural justice; and how to appropriately expand the use of remote technology while addressing key constitutional and legal issues.

This study provides a foundation for further exploration of court-user preferences and experiences with remote services and for additional research on ways judges and other court practitioners can overcome any loss of meaningful connection as noted here by court professionals. It also offers some indication that virtual hearings may be helpful in boosting attendance and access to the courts. But the data on technology availability makes clear that there is no one answer for every situation.

Flexibility in offering virtual and in-person alternatives could prove helpful in accommodating the various needs of individual court users and is in keeping with what many court users prefer. Despite the fact that court professionals tended to view interaction and rapport as better for in-person court compared to virtual, nearly half (46.8 percent) of the court staff respondents reported strong support for continuing virtual hearings, with many preferring a hybrid approach.

For court staff, holding more administrative meetings remotely may present an opportunity to increase efficiency. Sixty-one percent (61.2 percent) of court staff respondents reported strong support for continuing virtual pre-court staffings to discuss matters pertaining to ongoing cases.

As the pandemic continues, court leaders are likely to use studies like this one as well as their own experiences to determine what processes might continue remotely and what really needs to be done in person.