The foundation of our justice system is the jury trial. In criminal cases, the Sixth Amendment provides that “the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.”1 In civil cases, the Seventh Amendment guarantees the right of trial by jury on certain claims.2

Today, jury trials are vanishing. Many factors have led to this decline,3 and courts have struggled to assure the robust reality of our constitutional commitments. Over the years, the Western District of North Carolina (WDNC) has seen innovative approaches to improve access to and the presentation of jury trials. For example, in 2008, the WDNC developed the Jury Evidence Recording System (JERS) to give deliberating juries digital access to trial evidence. Later, the WDNC added electronic access to substantive jury instructions to JERS, allowing jurors to study those instructions together and in the privacy of the jury deliberation room. JERS was widely adopted in other states. Ultimately, in time, JERS may also make trial evidence available online to appellate courts and the public.

Courtroom design innovation came next. The “Virginia Model” courtroom4 is under construction in our new Courthouse Annex in uptown Charlotte; it will be one of the first such courtrooms built since the 18th century.5 (See illustration below.) The Virginia Model’s essential features are a center-based jury box underneath the judge, facing out; a witness box in the center of the well looking directly at the judge and jury; and counsel tables on each side. In the 18th century, the Commonwealth of Virginia county courts were intentionally designed this way to place the jury where it should be — at the center of a jury trial, as opposed to off to the side, symbolizing the jury’s shared authority with the judge.

These innovations reflect a passion for jury trial excellence. Unbeknownst to us, these innovations also would prove prescient; the changes anticipated the district’s (and perhaps the nation’s) greatest jury trial challenge — the COVID-19 virus. Many courts have reluctantly moved to the sidelines to wait out the pandemic. In the meantime, the federal judiciary undertook the challenge of how to resume jury trials amidst a global pandemic. The Administrative Office of the United States Courts (AO) created a COVID-19 Task Force to address the challenges that arose out of COVID-19. That task force in turn formed a “jury subgroup” that assembled a panel of judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers across the country, together with AO personnel, to guide courts in resuming jury trials. The author had the privilege of chairing the jury subgroup, which released a 16-page report titled “Conducting Jury Trials and Convening Grand Juries During the Pandemic.”6 This report, issued in June 2020 and comprising 15 sections, offers preliminary suggestions and ideas for courts to consider when restarting jury trials.7 The WDNC moved in lockstep with the AO. Relying on its prior courtroom-design thinking on the Virginia Model, the WDNC pursued reconfiguration of the courtroom to accommodate both trial imperatives on the one hand and safety and health concerns on the other. The WDNC contributed to, and adopted from, the AO jury subgroup’s recommendations concerning the jury trial process. This article discusses the steps taken and the lessons learned from a district-wide collaboration among lawyers, judges, and court staff to responsibly make jury trials a reality during the current pandemic.

Before reinstituting trials, the WDNC court staff repeatedly rehearsed what a potential trial might look like. After these rehearsals, in late May and early June 2020, the district took the next step: conducting mock trials in its Asheville and Charlotte courthouses and doing a walk-through (a condensed version of a mock trial) in its Statesville courthouse. In the mock trials, the United States Attorney’s Office presented a case based on a given fact pattern, and the Federal Public Defender’s Office provided representation to a mock defendant. Lawyers on the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) panel (criminal defense lawyers willing to accept appointments to defend individuals charged in federal court) and federal prosecutors were invited to attend the trial and offer suggestions, and a local reporter was even invited to participate as a mock juror. The district also set up a weekly teleconference with the criminal defense community to solicit input. During the mock trial, participants worked through many of the same issues faced by other courts: what the mask policy would be, whether the jury would be able to hear witnesses who chose to wear a mask, how to conduct a sidebar, and how to provide juror social distancing consistent with CDC standards, to name a few. After an evaluation of the mock trial process, the participating judges, attorneys, and court staff concluded that reconstituting jury trials was possible and that jury trials could be conducted safely and efficiently under the right conditions. After careful deliberation, we proceeded to the next step — actual jury trials. This article assesses lessons learned from the processes the district adopted.

The WDNC embraced the subgroup’s assessment that “one size does not fit all” in determining the appropriate time to reconvene juries. The report concludes, and we agree, that the timing

will differ state by state, district by district, and perhaps even division by division. Each court will need to review its state and local government’s “gating criteria” [indicators to assess when to move from one phase of COVID-19 mitigation to the next] in determining when to reconvene a petit or grand jury. Different institutions including the AO and the CDC have offered guidance to the gating criteria. The AO has provided guidance on health screening and use of masks that can be found included with the Director’s memorandum dated April 24, 2020. The CDC has provided a variety of documents with gating criteria guidance, including a comprehensive 60-page document. CDC guidance can be found on the CDC’s coronavirus page. Please note that such guidance is continually updated.8

The district embraced the subgroup’s decision-tree tool for workplace reopening and monitoring,9 and its board of judges met regularly through the spring to assess the current pandemic situation and its impact on courthouse reopenings locally and across the country. In so doing, the board of judges consulted guidance from officials and medical experts.

The district observed that the pandemic situation on the ground was different from district to district and even between divisions within a district. For example, the numbers of cases, percentages of new cases, and death rates varied in the three counties (Mecklenburg, Buncombe, and Iredell) where WDNC courthouses are located.10 And the configuration of each courtroom suggested different solutions. In Statesville, recent modifications to the jury box allowed it to seat 16 jurors. It was designed in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, allowing a smaller number of jurors (six to eight) to sit in the existing jury box in civil cases while still maintaining social distancing. In the older and unrenovated courtrooms in Asheville and Charlotte, the court decided to convert the gallery section of the courtroom into a jury box, creating sufficient space to make social distancing feasible for each juror. In Asheville, the large jury assembly room attached to the third-floor courtroom provided ample space for potential jurors in jury selection and for deliberating jurors during trial. In Charlotte, it was determined that the small jury assembly room on the first floor could not be used by potential jurors; instead, socially distanced seating was added to the hallway on the second floor, just outside the courtroom, converting it into a quasi jury assembly room for the dedicated trial courtroom on that floor. Proceeding from first principles — health concerns, social distancing, and the reconstitution of fair and just trials — the court made necessary and often differing adjustments in each courthouse.

Our design work here in Charlotte with the Virginia Model had introduced us to a “Virginia” jury trial concept, which featured a jury box centered underneath the judge facing out, a witness box in the middle of the well, and counsel tables on the sides. This led naturally to a “reverse-Virginia” concept, with a jury box in the spectator section of the courtroom, facing the witness stand in the middle of the well (still with counsel tables on the sides). The problem of the witness facing away from the judge was quickly solved by placing a camera in front of the witness that was broadcast to a screen for the judge.

Our design work here in Charlotte with the Virginia Model had introduced us to a “Virginia” jury trial concept, which featured a jury box centered underneath the judge facing out, a witness box in the middle of the well, and counsel tables on the sides. This led naturally to a “reverse-Virginia” concept, with a jury box in the spectator section of the courtroom, facing the witness stand in the middle of the well (still with counsel tables on the sides). The problem of the witness facing away from the judge was quickly solved by placing a camera in front of the witness that was broadcast to a screen for the judge.

The witness box was constructed with sufficient space for a small desk and chair to be placed on the six-foot by six-foot platform to aid the jury’s view of the witness. Counsel tables were placed on each side of the witness box, angled outward to aid the lawyers’ view of both the witness and the jury. At all times during trial, participants were confined to the well, and a red line was taped across the courtroom floor, creating a 12-foot buffer between trial participants and the jury. Participants entered the well each day from doors at the front of the courtroom, and jurors entered from the back.

This design was adopted in Charlotte and Asheville. The board of judges made the alternative location for civil trials the Statesville courthouse, where a smaller number of jurors (six to eight) could sit in the existing jury box and still maintain social distance.

Summonses were sent to 76 potential jurors for the first criminal trial held on June 12, 2020. A second set of summonses went to the jury pool for the second trial, which occurred on June 22.11 With the summonses, the court included a pre-screening questionnaire and letter describing the steps the court had taken to mitigate the risk of COVID-19.12 The letter allowed jurors to request to be excused if they were in a high-risk or vulnerable group.13 It also informed prospective jurors that the court had taken steps to minimize COVID-19 risk and maximize jurors’ health and safety, by providing front-door screening and PPE packages that included hand sanitizer, masks, and gloves.14 The prospective jurors were told that if selected as a juror, they would be isolated from other trial participants in the gallery section of the courtroom, would maintain social distance throughout the trial, and that the places they occupied in the courthouse would be repeatedly sanitized. Even with these precautionary steps, the prospective jurors were asked a series of COVID-19 questions consistent with CDC guidelines (i.e., had they been diagnosed with or experienced COVID-like symptoms in the past 14 days; were they over the age of 65; were they a care-provider for a high-risk individual or the sole provider for children at home because of school or daycare closings). An affirmative response to any of these questions offered the possibility of excusal, which was automatically granted if requested.

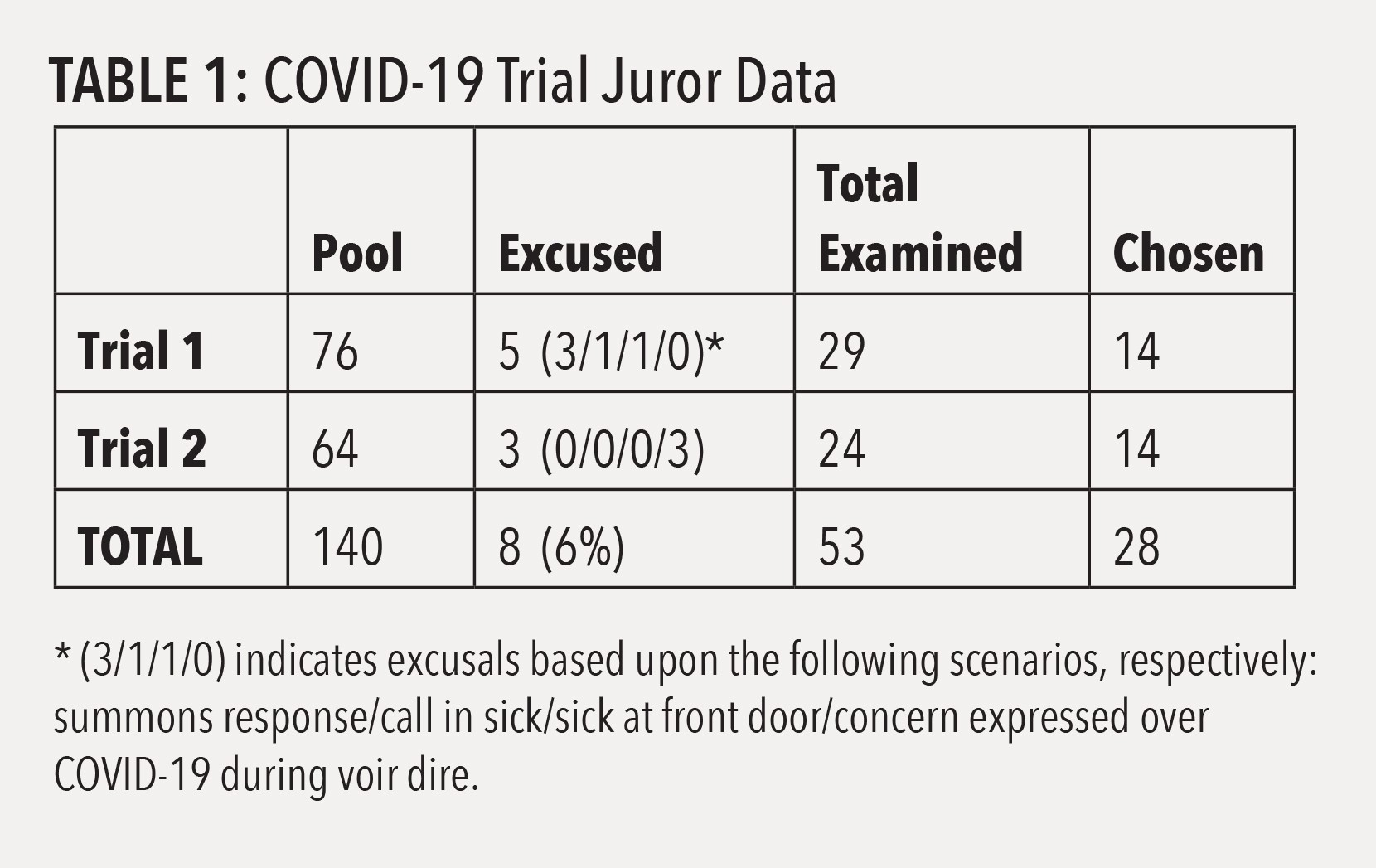

Of 76 potential jurors in the first trial, only three were excused automatically given their responses to the initial summons, one called in sick the day of trial, and one was sent home after a health screening by the nurse at the courthouse front door. The second trial produced even more dramatic results — no requests for excusal in response to the initial summons and accompanying COVID-19 letter. (See Table 1 at right.) Reports from a third trial (presided over by Judge Frank Whitney) and a fourth (presided over by Judge Max Cogburn) were similar. We learned as a district that citizens are passionate about jury service and are willing to perform their role in our justice system, notwithstanding the pandemic.

Of 76 potential jurors in the first trial, only three were excused automatically given their responses to the initial summons, one called in sick the day of trial, and one was sent home after a health screening by the nurse at the courthouse front door. The second trial produced even more dramatic results — no requests for excusal in response to the initial summons and accompanying COVID-19 letter. (See Table 1 at right.) Reports from a third trial (presided over by Judge Frank Whitney) and a fourth (presided over by Judge Max Cogburn) were similar. We learned as a district that citizens are passionate about jury service and are willing to perform their role in our justice system, notwithstanding the pandemic.

The district made the decision to cordon off the second floor of the Charlotte courthouse, enjoining any members of the public from entering that floor on trial days. The jurors became the sole occupants of the spectator section of the trial courtroom. The hallway was converted to a socially distanced jury assembly room, thus freeing up the first-floor jury assembly room to be allocated to public viewing. The trial proceedings were live-streamed to the converted first-floor jury assembly room, where members of the public could gather at a social distance and view the trial. Thus, the two-fold goal of safe, segregated, socially distanced trials and public access was maintained. The functions of the clerk’s office, which were usually performed on the second floor, were moved to other parts of the courthouse or offsite on trial days.

The morning of the trial, the jurors were scheduled to report to the courthouse in groups: 32 jurors in the morning; 32 in the afternoon; and 32 the next morning. They were immediately met with a health screening by a nurse hired by the court. The nurse took the temperature of all the jurors and asked them the prescribed CDC screening questions. She then provided each juror with a PPE kit that included a mask, gloves, and hand sanitizer.

To ensure adherence to social distancing guidelines, members of the jury pool waited on the second floor of the courthouse outside the courtroom for selection. Chairs and benches were dispersed six feet apart, and court employees placed stickers on the floor to mark off the correct distance jurors should stand from each other when they needed to move throughout the courthouse.

Sixteen jurors were brought into the courtroom for initial questioning. The presiding judge read a letter to the jury expressing the court’s gratitude and expectations for the jury’s service:

Our jury trial system is unique in the world. It is so because of you. As a citizen juror, you are doing great honor to yourself, your community and to our justice system. You the juror are the judge of the facts as the judge is the judge of the law. We share authority and responsibility that a fair trial by a jury of peers is provided to every defendant. You should be proud of this opportunity; we certainly are proud of you.

Now a few words about your service during a pandemic. You may be tempted to be apprehensive about your participation. We have taken steps to minimize that concern. I want to run through some of the things we have done to make this place safer; and to relieve any anxieties you may feel.

Each of you was pre-screened. That was done by letter notice asking if you, or someone you lived with, had any exposure history in the last 14 days; whether you had any symptoms, whether you were at increased risk due to age or underlying medical conditions. You were asked follow-up questions as you entered today. Anyone seated in this jury pool has passed this pre-screening process.

You were met at the door and your temperature was taken; you were given a PPE kit, and we committed ourselves to ensuring that you were able to practice social distancing and wear masks if you preferred.

You may notice that we created a jury box in what is usually the spectator gallery to help us help you maintain CDC-approved social distancing. You and you alone will occupy this part of the courtroom. Except for staff that will guide you at certain times to another courtroom, no one will enter your space. Any members of the public will watch in an overflow courtroom.

The court staff and the parties and lawyers will be in the well of the courtroom. You will never intersect with them. In fact, there is a line in the well of the courtroom the parties cannot cross.

We will give you the opportunity to wear masks. Some people will choose that option; others will not. The ability to tolerate masks for extended periods of time differs from person to person. You, the juror, will decide what is best for you.15

When we take longer breaks or when you begin your deliberations, we will escort you to another courtroom where you will have the same seat number assigned to you that you have here in this courtroom and you will have the opportunity to practice social distancing. You will leave first. Only when you arrive at your next stop will others be allowed to break. If we take a shorter break, you will be excused to the benches in the hallway that are also marked with your seat numbers.

These are a few of the things we have put in place to make your experience safer, to relieve any anxieties so that you may focus on the evidence.

The court asked specific voir dire questions relating to the jurors’ comfort levels about serving during a pandemic.16

In particular, jurors who chose to wear masks (the overwhelming majority) were asked if they were anxious about other jurors who chose not to wear masks. Any juror who responded with anxiety was excused. Again, the results are telling: Of the 53 jurors questioned in the two trials, only four asked to be excused for pandemic reasons. Combined with the four excused by letter or at the door, less than 6 percent of the jury pool asked to be excused. (See Table 1.) This is lower than the district’s excusal rate in the jury-selection process in non-pandemic cases and validates our court’s conclusion that — although subject to change due to the uncertainty and evolving nature of the virus — at least for now, in our district, the time is right for restarting the jury trial.

Parties were offered four options concerning sidebars. Option one was borrowed from Senior Judge Jim Jones in the Western District of Virginia who, when asked about his policy concerning sidebars, said, “I don’t have them.” Unsurprisingly, the lawyers rejected this option. Option two did not appeal to the judge. This was the “business as usual” model, where the lawyers approach the bench or at the “side” of the well and argue their motions or objections. For obvious reasons, this was deemed not a healthy option. Option three was disposable headsets with built-in microphones. This was tried and found to be at times unreliable. The sound quality was not consistently good enough, although this is one of the many innovations which holds out hope in the future. Option four suggested by the court was to hold text sidebars by a chat app created for that purpose, by Skype, or by a conventional messaging method. Eventually through trial and error, the court and counsel landed on sidebars heard in anterooms, including the now-unused deliberation room which was deemed large enough to accommodate social distance for the lawyers, judge, and court reporter.

The parties were informed that all evidence would be presented electronically, consistent with the way evidence is always presented in this district. Jurors, the witness, and the parties were provided individual monitors. Large screens were added in “belt and suspender” fashion on each side of the courtroom to further assist the jury. The court’s JERS program guaranteed that the jurors would have electronic access to admitted evidence during deliberations. Lawyers rejected the option of having the witness’s face enlarged on a screen for the benefit of the jury in the spectator section, opting instead for the jurors’ own perceptions of the witness on the stand. Witnesses waited in the conference rooms on the second floor. When called, they entered through a door in the front of the courtroom, took the oath at the temporary witness stand, and testified either with or without masks, depending on their individual preference. Jurors who provided post-trial feedback17 indicated no problem with hearing witnesses. After the testimony of each witness, the witness stand and Bible were sanitized.

The court promised social distancing space at each counsel table for a lawyer and his or her client. It also committed to extra measures to ensure client confidentiality, including disposable headsets with microphones set to a channel exclusively for attorney-client conversations, and anterooms for such meetings when needed. If counsel wanted additional personnel at counsel table, it was up to them to make the corresponding compromises with social distance. After one trial, court-appointed interpreters gave feedback that they would have preferred more space than was afforded behind the defense table.

Each of the trials involved incarcerated defendants. Any time an incarcerated defendant had to be moved, the jury was excused to another courtroom or to the hallway. Post-trial feedback indicated that jurors were surprised to learn that the defendants were in custody during the trial.

As previously addressed, jury deliberation occurred in a secondary courtroom on the same floor as the trial courtroom. When combined with social distancing, the ability to wear masks, and JERS access to evidence and jury instructions, deliberations seemed to work as efficiently as pre-pandemic deliberations. At least that was the feedback received post-trial. It is important to note that in one trial there was a conviction, and in another an acquittal. These outcomes reflect the importance of trying cases, if possible, despite pandemic conditions. Absent our willingness to work through the myriad challenges involved with trying cases during a pandemic, and the attorneys’ willingness to represent their clients with the court’s safety adjustments in place, one acquitted defendant would still be languishing in county jail.

There is a YouTube video circulating in which a man (it could just as easily have been a woman) is presented with his quarantine options. Option A is to shelter in place with his wife and child. As the narrator begins to explain Option B, the man answers “B.” Obviously, he was experiencing a great need to get out of the house. In a similar yet different manner, our fellow citizens feel a need not only to get out of the house but also to do something meaningful. Jury service provided that opportunity, and the jurors rose to the challenge. The jurors returned comments that expressed universal appreciation for the experience. Their comments were matched by the court’s appreciation for the essential service they so willingly and admirably performed.

The court conducted post-trial outreach to all who came to the courthouse for trial, including the selected jurors and those members of the jury pool who came but were not chosen. All were asked to report if, within 14 days, they were diagnosed with or experienced COVID symptoms. There were no such reports.

Overall, this court’s positive experience in four in-person jury trials demonstrates the possibilities for other courts to conduct similar trials. While each court will have to adjust and compromise as necessary, the WDNC demonstrated that constitutionally guaranteed trials can still be conducted while addressing the safety and health of jurors and trial participants. Although the pandemic may be the new normal for some time, innovative trial approaches may lead to benefits heretofore unimaginable far into the future. Our constitutional system depends upon the thoughtful reconstitution of the jury trial.

This thinking does not negate the grave seriousness the pandemic has and will continue to inflict on our beleaguered country. In this stressful time, when the scales of justice are challenged by the scale of the pandemic’s devastation, the American justice system must rise to this challenge and overcome. Within this district, the trials that have taken place have provided us with a sense of hope, not only for the future of the jury trial, but also for the citizens within this country. Although the future of the jury trial remains a dilemma for many, the Western District of North Carolina believes that the demands of justice will continue to be met and will overcome any “secret machinations, which may sap and undermine it,” even when those machinations turn out to be a global pandemic.18

Click here to download the accompanying appendix documents, including a sample letter to potential jurors outlining COVID-19 precautions; sample COVID-19 jury questions; and voir dire questions covering COVID-19 issues.

Footnotes: