by Gregory Mize and Thomas A. Balmer

Vol. 101 No. 1 (2017) | Citizen-centered Courts | Download PDF Version of Article

Many remember the alarming call to mission control from the Apollo 13 spacecraft crew. “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” Well, dear Judicature readers, we denizens of the judicial system have a very serious problem also. While we firmly believe Americans deserve a civil legal process that can fairly and promptly resolve disputes for everyone — rich or poor, individuals or businesses, in matters large or small — our civil justice system too often fails to meet this standard. Runaway costs, delays, and complexity are undermining public confidence and denying people the justice they seek. This article describes recent efforts taken by the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) to effectively address the shortcomings of our civil justice system.

Civil justice is relevant to all aspects of our lives and society, from public safety to fair housing to the smooth conduct of business. For centuries Americans have relied on an impartial judge or jury to resolve conflicts according to a set of rules that govern everyone equally. This framework is still the most reliable and democratic path to justice — and a vital affirmation that we live in a society where our rights are recognized and transparently protected. Yet navigating civil courts, as they operate now, can be daunting. Those who enter the system confront a maze-like process that costs too much and takes too long. While three-quarters of judgments are smaller than $5,200, the expense of litigation often greatly exceeds that amount. Small, uncomplicated matters that make up the overwhelming majority of cases can take years to resolve. Fearing the process is futile, many give up on pursuing justice altogether.

We have come to expect the services we use to steadily improve in step with our needs and new technologies. But in our civil justice system, these changes have largely not arrived. Many courts lack any of the user-friendly support we rely on in other sectors. To the extent technology is used, it simply digitizes a cumbersome process without making it easier. If our civil courts do not change how they work, they will meet the fate of travel agents or hometown newspapers, entities undone by new competition and customer expectations — but never adequately replaced.

Meanwhile, private entities are filling the void. Individuals and businesses today have many options for resolving disputes outside of court, including private judges for hire, arbitration, and online legal services, most of which do not require an attorney to navigate. But these alternatives cannot guarantee a transparent and impartial process. Existing common law does not necessarily bind these forums, nor does private ADR contribute to creating new common law to shape 21st-century justice. In short, they are not sufficiently democratic.

Restoring public confidence means rethinking how our courts work in fundamental ways. Citizens must be placed at the center of the system. They must be heard, respected, and capable of getting a just result, not just in theory but also in everyday practice. Courts need to embrace new procedures and technologies. They must give each matter the resources it needs — no more, no less — and prudently shepherd the cases our system faces now.

Confronted with these profound realities, the CCJ determined that it is imperative to examine the civil justice system holistically, consider the impact of the recent civil justice innovations, and develop a comprehensive set of recommendations for civil justice reform to meet the needs of the 21st century. At its 2013 Midyear Meeting, the CCJ adopted a resolution authorizing the creation of a special Civil Justice Improvements (CJI) Committee. The committee was charged with “developing guidelines and best practices for civil litigation based upon evidence derived from state pilot projects and from other applicable research, and informed by implemented rule changes and stakeholder input; and making recommendations as necessary in the area of caseflow management for the purpose of improving the civil justice system in state courts.”1

With the assistance of the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) and IAALS, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, the CCJ named a diverse 23-member committee, chaired by Oregon Chief Justice Thomas Balmer, to research and prepare the recommendations contained in this article. Committee members included key players in the civil litigation process, including trial and appellate court judges, trial and state court administrators, experienced civil lawyers representing the plaintiff and defense bars and legal aid, representatives of corporate legal departments, and legal academics.

The CJI Committee followed a set of nine fundamental principles to guide the development of recommedations: demonstrable impact on cost and delay; consistent with existing substantive law; protect right to a jury trial and procedural due process; capable of implementation across legal cultures and practices; supported by data, committee members’ experience, and “extreme common sense”; neutrality toward party identification, litagant type, and representation status; promote efficient use of resources and fairness; enhance public confidence.

With financial support from the State Justice Institute and substantive expertise and logistical support from NCSC and IAALS, the CJI Committee worked tirelessly over more than 18 months, reviewing existing research on the state of the civil justice system.

Two subcommittees undertook the bulk of the committee’s work. Judge Jerome Abrams, an experienced civil litigator and now trial court judge in Minnesota, led the Rules & Litigation Subcommittee. That subcommittee focused on the role of court rules and procedures in achieving a just and efficient civil process, including developing recommendations regarding court and judicial management of cases, right sizing the process to meet the needs of cases, early identification of issues for resolution, the role of discovery, and civil case resolution, whether by way of settlement or trial.

Judge Jennifer Bailey, the administrative judge of the Circuit Civil Division in Miami with 24 years of experience as a trial judge, chaired the Court Operations Subcommittee. That subcommittee examined the role of the internal infrastructure of the courts — including routine business practices, staffing and staff training, and technology — in moving cases towards resolution, so that trial judges can focus their attention on ensuring fair and cost-effective justice for litigants. The subcommittee also considered the special issues of procedural fairness that often arise in “high volume” civil cases such as debt collection, landlord-tenant, and foreclosure matters, where one party often is not represented by a lawyer.

The subcommittees held monthly conference calls to discuss discrete issues related to their respective work. Individual committee members circulated white papers, suggestions, and discussion documents. Spirited conversations led members to reexamine long-held views about the civil justice system, in light of the changing nature of the civil justice caseload, innovations in procedures and operations from around the country, the rise of self-represented litigants, and the challenge and promise of technology. The full CJI Committee met in four plenary sessions over the course of this project to share insights and preliminary proposals. Gradually, committee members came to consensus on the recommendations set out in this article.

To inform the CJI Committee’s deliberations, the NCSC undertook a multijurisdictional study of civil caseloads in state courts. Entitled The Landscape of Civil Litigation in State Courts, the study focused on nondomestic civil cases disposed between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2013, in state courts exercising civil jurisdiction in 10 urban counties.2 The dataset, encompassing nearly one million cases, reflects approximately five percent of civil cases nationally.

The Landscape findings presented a very different picture of civil litigation than most lawyers and judges envisioned based on their own experiences and on common criticisms of the American civil justice system. Although high-value tort and commercial contract disputes are the predominant focus of contemporary debates, collectively they comprised only a small proportion of the Landscape caseload. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of the caseload was contract cases. The vast majority of those were debt collection, landlord/tenant, and mortgage foreclosure cases (39 percent, 27 percent, and 17 percent, respectively). An additional sixteen percent of civil caseloads were small claims cases involving disputes valued at $12,000 or less, and nine percent were characterized as “other civil” cases involving agency appeals and domestic or criminal-related cases. Only seven percent were tort cases and one percent were real property cases.

The composition of contemporary civil caseloads stands in marked contrast to caseloads of two decades ago. The NCSC undertook secondary analysis comparing the Landscape data with civil cases disposed in 1992 in 45 urban general jurisdiction courts. In the 1992 Civil Justice Survey of State Courts, the ratio of tort to contract cases was approximately 1:1. In the Landscape dataset, this ratio had increased to 1:7. While population-adjusted contract filings fluctuate somewhat due to economic conditions, they have generally remained fairly flat over the past 30 years. Tort cases, in contrast, have largely evaporated.

To the extent that damage awards recorded in the final judgment are a reliable measure of the monetary value of civil cases, the cases in the Landscape dataset involved relatively modest sums. In contrast to widespread perceptions that much civil litigation involves high-value commercial and tort cases, only 0.2 percent had judgments that exceeded $500,000, and only 165 cases (less than 0.1 percent) had judgments that exceeded $1 million. Instead, 90 percent of all judgments entered were less than $25,000; 75 percent were less than $5,200.3

Hence, for most litigants, the costs of litigating a case through trial would greatly exceed the monetary value of the case. In some instances, the costs of even initiating the lawsuit or making an appearance as a defendant would exceed the value of the case. The reality of litigation costs routinely exceeding the value of cases explains the relatively low rate of dispositions involving any form of formal adjudication. Only four percent of cases were disposed by bench or jury trial, summary judgment, or binding arbitration. The overwhelming majority (97 percent) of these were bench trials, almost half of which (46 percent) took place in small claims or other civil cases. Three-quarters of judgments entered in contract cases following a bench trial were less than $1,800. This is not to say these cases are insignificant to the parties. Indeed the stakes in many cases involve fundamentals like employment and shelter. However the judgment data contradicts the assumption that many bench trials involve adjudication of complex, high-stakes cases.

Most cases were disposed through a nonadjudicative process. A judgment was entered in nearly half (46 percent) of the Landscape cases, most of which were likely default judgments. One-third of cases were dismissed (possibly following a settlement although only 10 percent were explicitly coded by the courts as settlements). Summary judgment is a much less favored disposition in state courts compared to federal courts. Only one percent were disposed by summary judgment. Most of these would have been default judgments in debt collection cases, but the plaintiff instead chose to pursue summary judgment, presumably to minimize the risk of post-disposition challenges.

The traditional view of the adversarial system assumes the presence of competent attorneys zealously representing both parties. One of the most striking findings in the Landscape dataset, therefore, was the relatively large proportion of cases (76 percent) in which at least one party was unrepresented, usually the defendant. Tort cases were the only case type in which attorneys represented both parties in a majority (64 percent) of cases. Surprisingly, small claims dockets in the Landscape courts had an unexpectedly high proportion (76 percent) of plaintiffs who were represented by attorneys. This suggests that small claims courts, which were originally developed as a forum for self-represented litigants to access courts through simplified procedures, have become the forum of choice for attorney-represented plaintiffs in debt collection cases.

Approximately three-quarters of cases were disposed in just over one year (372 days), and half were disposed in just under four months (113 days). Nevertheless, small claims were the only case type that came close to complying with the Model Time Standards for State Trial Courts.4 Tort cases were the worst-case category in terms of compliance with the Standards. On average, tort cases took 16 months (486 days) to resolve and only 69 percent were disposed within 540 days of filing compared to 98 percent recommended by the Standards.

In response to these realities, the CJI Committee found that courts must improve how they serve citizens in terms of efficiency, cost, and convenience, and they must make the court system a more attractive option to achieve justice in civil cases. The committee’s recommendations address the contemporary reality of the civil justice system and offer a blueprint for restoring function and faith in a system that is too important to lose. The following pages set forth the CJI Committee’s recommendations and major portions of the accompanying commentaries. The full text of the commentaries, key resources, and appendices5 are available for downloading at NCSC.org/civil.

1.1 Throughout the life of each case, courts must effectively communicate to litigants all requirements for reaching just and prompt case resolution. These requirements, whether mandated by rule or administrative order, should at a minimum include a firm date for commencing trial and mandatory disclosures of essential information.

1.2 Courts must enforce rules and administrative orders that are designed to promote the just, prompt, and inexpensive resolution of civil cases.

1.3 To effectively achieve case management responsibility, courts should undertake a thorough statewide civil docket inventory.

COMMENTARY

Our civil justice system has historically expected litigants to drive the pace of civil litigation by moving for court involvement as issues arise. This often results in delay as litigants wait in line for attention from a passive court — be it for rulings on motions, a requested hearing, or even setting a trial date. The wait-for-a-problem paradigm effectively shields courts from responsibility for the pace of litigation. It also presents a special challenge for self-represented litigants who are trying to understand and navigate the system. The party-take-the-lead culture can encourage delay strategies by attorneys, whose own interests and the interests of their clients may favor delay rather than efficiency. In short, adversarial strategizing can undermine the achievement of fair, economical, and timely outcomes.

It is time to shift this paradigm. The Landscape of Civil Litigation makes clear that relying on parties to self-manage litigation is often inadequate. At the core of the committee’s recommendations is the premise that the courts ultimately must be responsible for assuring access to civil justice. Once a case is filed in court, it becomes the court’s responsibility to manage the case toward a just and timely resolution. When we say “courts” must take responsibility, we mean judges, court managers, and indeed the whole judicial branch, because the factors producing unnecessary costs and delays have become deeply imbedded in our legal system. Primary case responsibility means active and continuing court oversight that is proportionate to case needs. This right-sized case management involves having the most appropriate court official perform the task at hand and supporting that person with the necessary technology and training to manage the case toward resolution. At every point in the life of a case, the right person in the court should have responsibility for the case.

RE: 1.1

The court, including its personnel and IT systems, must work in conjunction with individual judges to manage each case toward resolution. Progress in resolving each case is generally tied both to court events and to judicial decisions. Effective caseflow management involves establishing presumptive deadlines for key case stages including a firm trial date. In overseeing civil cases, relevant court personnel should be accessible, responsive to case needs, and engaged with the parties — emphasizing efficiency and timely resolution.

RE: 1.2

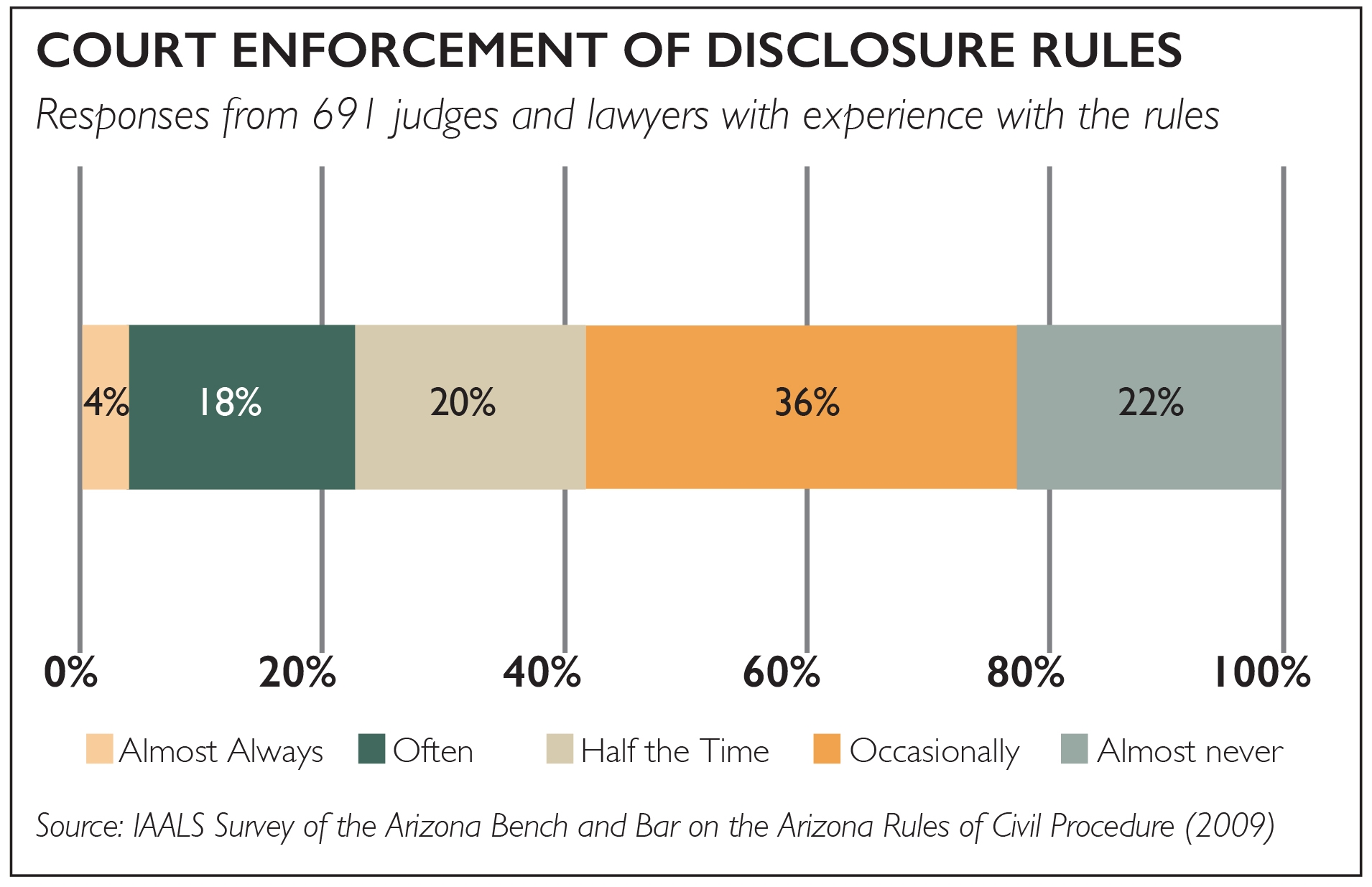

During numerous meetings, committee members voiced strong concern (and every participating trial lawyer expressed frustration) that, despite the existence of well-conceived rules of civil procedure in every jurisdiction, judges too often do not enforce the rules. These perceptions are supported by empirical studies showing that attorneys want judges to hold practitioners accountable to the expectations of the rules. For example, the chart at right summarizes results of a 2009 survey of the Arizona Trial Bar about court enforcement of mandatory disclosure rules.

During numerous meetings, committee members voiced strong concern (and every participating trial lawyer expressed frustration) that, despite the existence of well-conceived rules of civil procedure in every jurisdiction, judges too often do not enforce the rules. These perceptions are supported by empirical studies showing that attorneys want judges to hold practitioners accountable to the expectations of the rules. For example, the chart at right summarizes results of a 2009 survey of the Arizona Trial Bar about court enforcement of mandatory disclosure rules.

Surely, whenever it is customary to ignore compliance with rules “designed to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding,”6 cost and delay in civil litigation will continue.

RE: 1.3

Courts cannot meaningfully address an issue without first knowing its contours. Analyzing the existing civil caseload provides these contours and gives court leaders a basis for informed decisions about what needs to be done to ensure civil docket progression.

COMMENTARY

Virtually all states have followed the federal model and adopted a single set of rules, usually similar and often identical to the federal rules, to govern procedure in civil cases. Unfortunately, this pervasive one-size-fits-all approach too often fails to recognize and respond effectively to individual case needs.

The one-size-fits-all mentality exhibits itself at multiple levels. Even where innovative rules are implemented with the best of intentions, judges often continue to apply the same set of rules and mindset to the cases before them. When the same approach is used in every case, judicial and staff resources are misdirected toward cases that do not need that kind of attention. Conversely, cases requiring more assistance may not get the attention they require because they are lumped in with the rest of the cases and receive the same level of treatment. Hence the civil justice system repeatedly imposes unnecessary, time-consuming steps, making it inaccessible for many litigants.

Courts need to move beyond monolithic methods and recognize the importance of adapting court process to case needs. The committee calls for a “right sizing” of court resources. Right sizing aligns rules, procedures, and court personnel with the needs and characteristics of similarly situated cases. As a result, cases get the amount of process needed — no more, no less. With right sizing, judges tailor their oversight to the specific needs of cases. Administrators align court resources to case requirements, coordinating the roles of judges, staff, and infrastructure.

With the advent of e-filing, civil cover sheets, and electronic case-management systems, courts can use technology to begin to right size case management at the time of filing. Technology can also help identify later changes in a case’s characteristics that may justify management adjustments.

This recommendation, together with Recommendation 1, add up to an imperative: Every case must have an appropriate plan beginning at the time of filing, and the entire court system must execute the plan until the case is resolved.

A. TRIAGE CASE FILINGS WITH MANDATORY PATHWAY ASSIGNMENTS

3.1 To best align court management practices and resources, courts should utilize a three-pathway approach: Streamlined, Complex, and General.

3.2 To ensure that court practices and resources are aligned for all cases throughout the life of the case, courts must triage cases at the time of filing based on case characteristics and issues.

3.3 Courts should make the pathway assignments mandatory upon filing.

3.4 Courts must include flexibility in the pathway approach so that a case can be transferred to a more appropriate pathway if significant needs and circumstances change.

3.5 Alternative dispute-resolution mechanisms can be useful on any of the pathways provided that they facilitate the just, speedy, and inexpensive disposition of civil cases.

COMMENTARY

The premise behind the pathway approach is that different types of cases need different levels of case management and different rules-driven processes. Data and experience tell us that cases can be grouped by their characteristics and needs. Tailoring the involvement of judges and professional staff to those characteristics and needs will lead to efficiencies in time, scale, and structure. To achieve these efficiencies, it is critical that the pathway approach be implemented at the individual case level and consistently managed on a system-wide basis from the time of filing.

Implementing this right-size approach is similar to, but distinct from, differentiated case management (DCM). DCM is a long-standing case-management technique that applies different rules and procedures to different cases based on established criteria. In some jurisdictions, the track determination is made by the judge at the initial case-management conference. Where assignment to a track is more automatic or administratively determined at the time of filing, it is usually based merely on case type or amount in controversy. There has been a general assumption that a majority of cases will fall in a middle track, and it is the exceptional case that needs more or less process.

While the tracks and their definitions may be in the rules, it commonly falls upon the judges to assign cases to an appropriate track. Case automation or staff systems are rarely in place to ensure assignment and right-sized management, or to evaluate use of the tracking system. Thus, while DCM is an important concept upon which these recommendations build, in practice it has fallen short of its potential. The right-sized case-management approach recommended here embodies a more modern approach than DCM by (1) using case characteristics beyond case type and amount in controversy, (2) requiring case triaging at time of filing, (3) recognizing that the great majority of civil filings present uncomplicated facts and legal issues, and (4) requiring utilization of court resources at all levels, including nonjudicial staff and technology, to manage cases from the time of filing until disposition.

[ STREAMLINED PATHWAY ]

4.1 A well-established streamlined pathway conserves resources by automatically calendaring core case processes. This approach should include the flexibility to allow court involvement and/or management as necessary.

4.2 At an early point in each case, the court should establish deadlines to complete key case stages including a firm trial date. The recommended time to disposition for the streamlined pathway is six to eight months.

4.3 To keep the discovery process proportional to the needs of the case, courts should require mandatory disclosures as an early opportunity to clarify issues, with enumerated and limited discovery thereafter.

4.4 Judges must manage trials in an efficient and time-sensitive manner so that trials are an affordable option for litigants who desire a decision on the merits.

COMMENTARY

Streamlined civil cases are those with a limited number of parties, routine issues related to liability and damages, few anticipated pretrial motions, limited need for discovery, few witnesses, minimal documentary evidence, and anticipated trial length of one to two days. Streamlined pathway cases would likely include these case types: automobile tort, intentional tort, premises liability, tort–other, insurance coverage claims arising out of claims listed above, landlord/tenant, buyer plaintiff, seller plaintiff, consumer debt, contract–other, and appeals from small claims decisions. For these simpler cases, it is critical that the process not add costs for the parties, particularly when a large percentage of cases end early in the pretrial process. Significantly, the Landscape of Civil Litigation informs us that 85 percent of all civil case filings fit within this category.

[ COMPLEX PATHWAY ]

5.1 Courts should assign a single judge to complex cases for the life of the case, so they can be actively managed from filing through resolution.

5.2 The judge should hold an early case-management conference, followed by continuing periodic conferences or other informal monitoring.

5.3 At an early point in each case, the judge should establish deadlines for the completion of key case stages including a firm trial date.

5.4 At the case-management conference, the judge should also require the parties to develop a detailed discovery plan that responds to the needs of the case, including mandatory disclosures, staged discovery, plans for the preservation and production of electronically stored information, identification of custodians, and search parameters.

5.5 Courts should establish informal communications with the parties regarding dispositive motions and possible settlement, so as to encourage early identification and narrowing of the issues for more effective briefing, timely court rulings, and party agreement.

5.6 Judges must manage trials in an efficient and time-sensitive manner so that trials are an affordable option for litigants who desire a decision on the merits.

COMMENTARY

The complex pathway provides right-sized process for those cases that are complicated in a variety of ways. Such cases may be legally complex or logistically complex, or they may involve complex evidence, numerous witnesses, or high interpersonal conflict. Cases in this pathway may include multiparty medical malpractice, class actions, antitrust, multiparty commercial cases, securities, environmental torts, construction defect, product liability, and mass torts. While these cases comprise a very small percentage (generally no more than 3 percent) of most civil dockets, they tend to utilize the highest percentage of court resources.

Some jurisdictions have developed a variety of specialized courts such as business courts, commercial courts, and complex litigation courts. They often employ case-management techniques recommended for the complex pathway in response to long-standing recognition of the problems complex cases can pose for effective civil case processing. While implementation of a mandatory pathway-assignment system may not necessarily replace a specialized court with the complex pathway, courts should align their case-assignment criteria for the specialized court to those for the complex pathway. As many business and commercial court judges have discovered, not all cases featuring business-to-business litigants or issues related to commercial transactions require intensive case management. Conversely, some cases that do not meet the assignment criteria for a business or commercial court do involve one or more indicators of complexity and should receive close individual attention.

[ GENERAL PATHWAY ]

RECOMMENDATION 6. Courts should implement a general pathway for cases whose characteristics do not justify assignment to either the streamlined or complex pathway.

6.1 At an early point in each case, the court should establish deadlines for the completion of key case stages, including a firm trial date. The recommended time to disposition for the general pathway is 12 to 18 months.

6.2 The judge should hold an early case-management conference upon request of the parties. The court and the parties must work together to move these cases forward, with the court having the ultimate responsibility to guard against cost and delay.

6.3 Courts should require mandatory disclosures and tailored additional discovery.

6.4 Courts should utilize expedited approaches to resolving discovery disputes to ensure cases in this pathway do not become more complex than they need to be.

6.5 Courts should establish informal communications with the parties regarding dispositive motions and possible settlement, so as to encourage early identification and narrowing of the issues for more effective briefing, timely court rulings, and party agreement.

6.6 Judges must manage trials in an efficient and time-sensitive manner so that trials are an affordable option for litigants who desire a decision on the merits.

COMMENTARY

Like the other pathways, the goal of the general pathway is to determine and provide “right-sized” resources for timely disposition. The general pathway provides the right amount of process for the cases that are not simple, but are also not complex. Thus, general pathway cases are those cases that are principally identified by what they are not, as they do not fit into either the streamlined pathway or the highly managed pathway. Nevertheless, the general pathway is not another route to “litigation as we know it.” Like the streamlined cases, discovery and motions for these cases can become disproportionate, with efforts to discover more than what is needed to support claims and defenses. The goal for this pathway is to provide right-sized process with increased judicial involvement as needed to ensure that cases progress toward efficient resolution.

As with the other case pathways, at an early point in each case courts should set a firm trial date. Proportional discovery, initial disclosures, and tailored additional discovery are also essential for keeping general pathway cases on track.

B. STRATEGICALLY DEPLOY COURT PERSONNEL & RESOURCES

7.1 Courts should conduct a thorough examination of their civil case business practices to determine the degree of discretion required for each management task. These tasks should be performed by persons whose experience and skills correspond with the task requirements.

7.2 Courts should delegate administrative authority to specially trained staff to make routine case-management decisions.

COMMENTARY

Recommendation 1 sets forth the fundamental premise that courts are primarily responsible for the fair and prompt resolution of each case. This is not the responsibility of the judge alone. Active case management at its best is a team effort aided by technology and appropriately trained and supervised staff. The committee rejects the proposition that a judge must manage every aspect of a case after its filing. Instead the committee endorses the proposition that court personnel, from court staff to judge, be utilized to act at the “top of their skill set.”

Team case management works. Utah’s implementation of team case management resulted in a 54 percent reduction in the average age of pending civil cases from 335 days to 192 days (and a 54 percent reduction for all case types over that same period) despite considerably higher caseloads. In Miami, team case management resulted in a 25 percent increase in resolved foreclosure cases compared consistently at six months, 12 months, and 18 months during the foreclosure crisis, and the successful resolution of a 50,000-case backlog. Specialized business courts across the country use team case management with similar success. In Atlanta, business court efforts resulted in a 65 percent faster disposition time for complex contract cases and a 56 percent faster time for complex business-tort cases.

COMMENTARY

Judicial training is not a regular practice in every jurisdiction. To improve — and in some instances reengineer — civil case management, jurisdictions should establish a comprehensive judicial-training program. The committee advocates a civil case-management training program that includes web-based training modules, regular training of new judges and sitting judges, and a system for identifying judges who could benefit from additional training.

Accumulated learning from the private sector suggests that the skill sets required for staff will change rapidly and radically over the next several years. Staff training must keep up with the impact of technology improvements and consumer expectations. For example, court staff should be trained to provide appropriate help to self-represented litigants. Related to that, litigants should be given an opportunity to perform many court transactions online. Even with well-designed websites and interfaces, users can become confused or lost while trying to complete these transactions. Staff training should include instruction on answering user questions and solving user-process problems.

The understanding and cooperation of lawyers can significantly influence the effectiveness of any pilot projects, rules changes, or case management processes that court leaders launch. Judges and court administrators must partner with the bar to create CLE programs and bench/bar conferences that help practitioners understand why changes are being undertaken and what will be expected of lawyers. Bar organizations, like the judicial branch, must design and offer education programs to inform their members about important aspects of the new practices being implemented in the courts.

COMMENTARY

The committee recognizes the variety of legal cultures and customs that exist across the breadth of our country. Given the case management imperatives described in these recommendations, the committee trusts that all court leaders will make judicial competence a high priority. Court leaders should consider a judge’s particular skill sets when assigning judges to preside over civil cases. For many years, in most jurisdictions, the primary criteria for judicial assignment were seniority and a judge’s request for an assignment. The judge’s experience or training were not top priorities.

To build public trust in the courts and improve case-management effectiveness, it is incumbent upon court leaders to avoid politicization of the assignment process. In assigning judges to various civil case dockets, court leaders should consider a composite of factors including: (1) demonstrated case management skills, (2) litigation experience, (3) previous training, (4) specialized knowledge, (5) interest, (6) reputation with respect to neutrality, and (6) professional standing within the trial bar.

C. USE TECHNOLOGY WISELY

10.1 Courts must use technology to support a court-wide teamwork approach to case management.

10.2 Courts must use technology to establish business processes that ensure forward momentum of civil cases.

10.3 To measure progress in reducing unnecessary cost and delay, courts must regularly collect and use standardized, real-time information about civil case management.

10.4 Courts should use information technology to inventory and analyze their existing civil dockets.

10.5 Courts should publish measurement data as a way to increase transparency and accountability, thereby encouraging trust and confidence in the courts.

COMMENTARY

This recommendation is fundamental to achieving effective case management. To implement right-sized case management, courts must have refined capacities to organize case data, notify interested persons of requirements and events, monitor rules compliance, expand litigant understanding, and prompt judges to take necessary actions. To meet these urgent needs, courts must fully employ information technologies to manage data and business processes. It is time for courts to catch up with the private sector. The expanding use of online case filing and electronic case management is an important beginning — but just a beginning. Enterprises as diverse as commercial air carriers, online retailers, and motor vehicle registrars have demonstrated ways to manage hundreds of thousands of transactions and communications. What stands in the way of courts following suit? If it involves lack of leadership, the committee trusts that these recommendations will embolden chief justices and state court administrators to fill that void.

D. FOCUS ATTENTION ON HIGH-VOLUME AND UNCONTESTED CASES

11.1 Courts must implement systems to ensure that the entry of final judgments complies with basic procedural requirements for notice, standing, timeliness, and sufficiency of documentation supporting the relief sought.

11.2 Courts must ensure that litigants have access to accurate and understandable information about court processes and appropriate tools, such as standardized court forms and checklists for pleadings and discovery requests.

11.3 Courts should ensure that the courtroom environment for proceedings on high-volume dockets minimizes the risk that litigants will be confused or distracted by over-crowding, excessive noise, or inadequate case calls.

11.4 Courts should, to the extent feasible, prevent opportunities for self-represented persons to become confused about the roles of the court and opposing counsel.

COMMENTARY

State court caseloads are dominated by lower-value contract and small claims cases rather than high-value commercial or tort cases. Many courts assign these cases to specialized court calendars such as landlord/tenant, consumer debt collection, mortgage foreclosure, and small claims dockets. Many of these cases exhibit similar characteristics. For example, few cases are adjudicated on the merits, and almost all of those are bench trials. Although plaintiffs are generally represented by attorneys, defendants in these cases are overwhelmingly self-represented, creating an asymmetry in legal expertise that, without effective court oversight, can easily result in unjust case outcomes. Although most cases would be assigned to the streamlined pathway under these recommendations, courts should attend to signs that suggest a case might benefit from additional court involvement. Indicators can include the raising of novel claims or defenses that merit closer scrutiny.

12.1 To prevent uncontested cases from languishing on the docket, courts should monitor case activity and identify uncontested cases in a timely manner. Once uncontested status is confirmed, courts should prompt plaintiffs to move for dismissal or final judgment.

12.2 Final judgments must meet the same standards for due process and proof as contested cases.

COMMENTARY

Uncontested cases comprise a substantial proportion of civil caseloads. In the Landscape of Civil Litigation in State Courts, the NCSC was able to confirm that default judgments comprised 20 percent of dispositions, and an additional 35 percent of cases were dismissed without prejudice. Many of these cases were abandoned by the plaintiff or the parties reached a settlement, but failed to notify the court. Other studies of civil caseloads also suggest that uncontested cases comprise a substantial portion of civil cases (e.g., 45 percent of civil cases subject to the New Hampshire Proportional Discovery/Automatic Disclosure (PAD) Rules, 84 percent of civil cases subject to Utah Rule 26). Without effective oversight, these cases can languish on court dockets indefinitely. For example, more than one-quarter of the Landscape cases that were dismissed without prejudice were pending at least 18 months before they were dismissed.

RE 12.1

To resolve uncontested matters promptly yet fairly requires focused court action. Case-management systems should be configured to identify uncontested cases shortly after the deadline for filing an answer or appearance has elapsed. If the plaintiff fails to file a timely motion for default or summary judgment, the court should order the plaintiff to file such a motion within a specified period of time. If such a motion is not filed, the court should dismiss the case for lack of prosecution. The court should monitor compliance with the order and carry out enforcement as needed.

NEXT STEPS

The CJI Committee’s recommendations advocate “what” state courts must do to address the evident urgencies in the civil justice system. While many of the recommendations can be implemented within existing budgets and under current rules of procedure, others will require significant change and steadfast, strong leadership to achieve that change. In the CCJ resolution endorsing the recommendations, the CCJ addressed “how” court leaders can overcome barriers to needed changes and actually deliver better civil justice. The conference encouraged “each state to develop and implement a civil justice improvements plan to improve the delivery of civil justice.” The CCJ Resolution characterized the recommendations as a “worthy guide” for the states and directed the NCSC “to take all available and reasonable steps to assist court leaders who desire to implement civil justice improvements.”8 In the few months since the CCJ made its call for action, implementation strategies have begun to form.

COURT AND STAKEHOLDER STRATEGIES

As discussed earlier, the NCSC’s Landscape of Civil Litigation provided a template for problem identification, big-picture visioning, and strategic planning by state and local courts. The Landscape became so central to the formation of the recommendations that the CJI Committee, in its final communication to the full CCJ, urged each state court to undertake its own landscape study. Such a study would not only enable court leaders to diagnose the volume and characteristics of civil case dockets across their state, but would also help identify major barriers to reducing cost, delay, and inefficiency in civil litigation. Leaders can then sequence and execute strategies to surmount those barriers.

The CJI Committee also suggested that court leaders build internal support for change. This suggestion derived from the experience of the committee during its two years of work. Thanks again to the Landscape, this diverse group of judges, court managers, trial practitioners, and organization leaders started their work with an accurate picture of the civil litigation system. From across the country, they collected a sampling of best practices that demonstrate smart case management and superior citizen access to justice. They then closely analyzed and discussed the data over the course of several in-person, plenary meetings and innumerable conference calls and email exchanges. What resulted? Unanimous and enthusiastic support for major civil justice improvements. And, for each committee member, there arose strong convictions: The quality and vitality of the civil justice system is severely threatened. Now is the time for strong leadership by all chief justices and court administrators. Frontline judges and administrators must have the opportunity to ponder facts about the civil justice system in their state. Once that opportunity and those deliberations occur, a wellspring of support for civil justice improvement will take shape within the judiciary. With a supportive judicial branch, courts can face down tough issues and undertake needed courthouse improvements. What’s more, a unified judiciary will also facilitate external stakeholder participation.

The CJI Committee also made clear that court improvement efforts must involve the bar. The committee pointed to the Washington State Bar as a prime example of lawyers, sobered by evidence of growing civil litigation costs, taking bold actions to improve the fair resolution of civil cases. After four years of labor, the Bar’s Task Force on the Escalating Costs of Civil Litigation issued a series of recommendations to make courts affordable and accessible. The principles of proportionality and cooperation infuse the recommendations. In the words of the Task Force, “Lowering litigation costs depends on keeping the costs of cases proportional to their needs. . . .”* With respect to cooperation, the recommendations close by saying, “[t]he Task Force urges the Board [of Governors] not only to adopt these recommendations, but to help educate the judges and lawyers who will be responsible for making the recommendations a reality.”9

Several other lawyer groups provided significant input to the CJI Committee’s work. These include the American Board of Trial Advocates, the American Civil Trial Roundtable, the American College of Trial Lawyers, the National Creditors Bar Association, IAALS’ Advisory Groups, and the NCSC’s General Counsel Committee, Lawyers’ Committee, and Young Lawyers’ Committee. Some of these groups have state counterparts that can collaborate with court leaders to implement civil justice improvements that befit their state or locality. The committee trusts those alliances can also lead to focus groups that educate key constituencies about their state’s top civil justice needs and the probable effectiveness of many of the recommendations.

Perhaps Judicature readers also will advocate for some recommendations using the CJI Committee’s proposals and evidence-based resources to build understanding and trust among the general public.

FUTURE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO STATE COURTS

Recognizing that organizational change is a process, not an event, the National Center for State Courts and IAALS are collaborating to assist court leaders who desire to implement civil justice change. With generous financial support from the State Justice Institute, the NCSC and IAALS have begun a three-year project to implement the CJI Recommendations across the country. The CJI Implementation Plan is a multifaceted effort involving education, technical assistance, and practical tools to help state and local courts with implementation efforts, as well as several pilot projects to demonstrate the impact that these recommendations have on effective civil case management. Additional information is available at www.ncsc.org/civil.