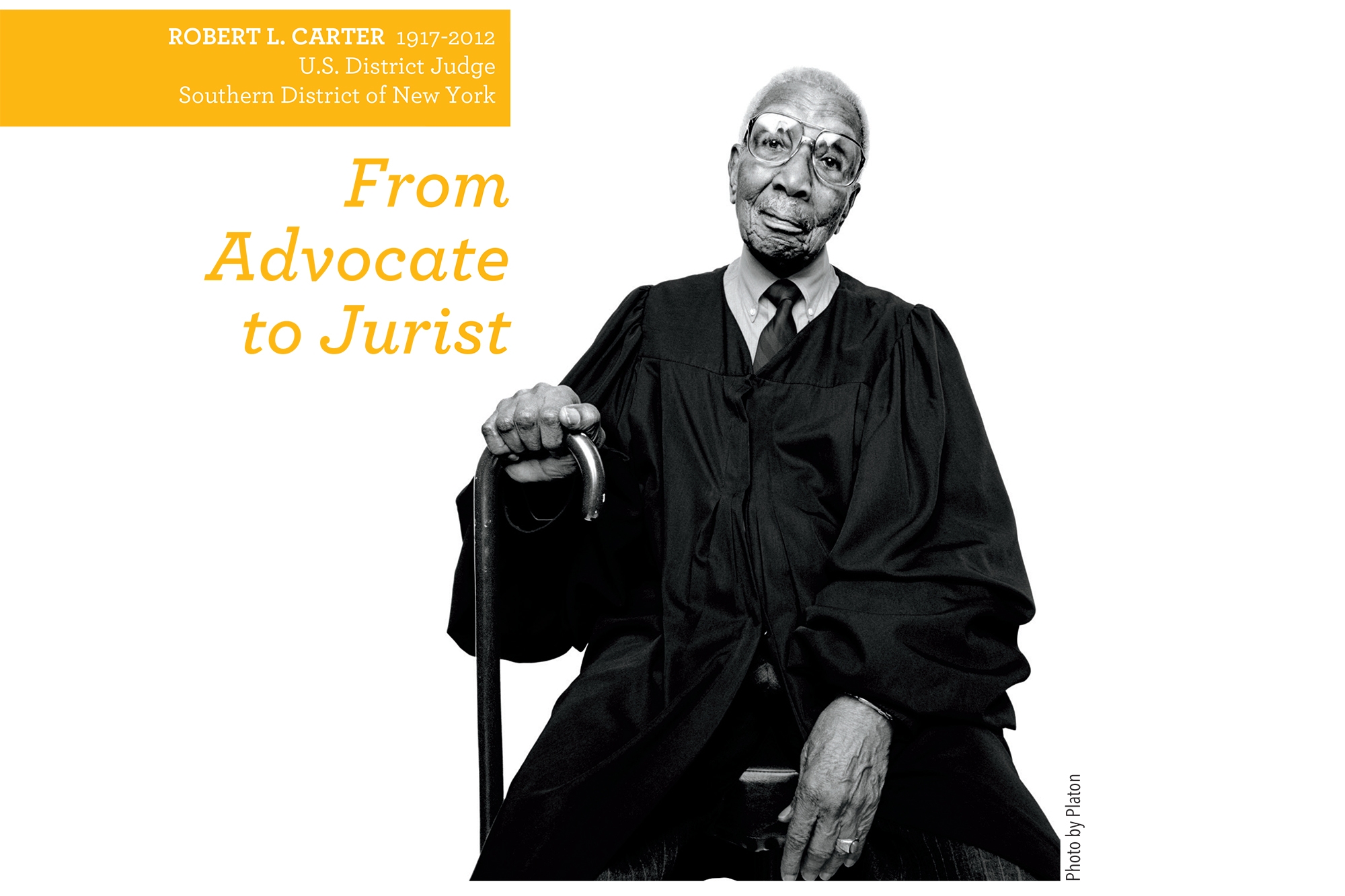

As an NAACP Lawyer, Robert L. Carter litigated countless milestone cases, including Brown v. Board of Education. He was such a passionate voice for civil rights that it might appear incongruous that he could settle into the role of a neutral arbiter. Yet, he ultimately devoted nearly 40 years to serving as a United States district judge in the Southern District of New York.

That Bob Carter committed himself to challenging inequality is understandable, since he experienced discrimination on a personal level long before he began his legal career. As a black teenager growing up in New Jersey in the 1930s, Bob was barred from participating in swimming class with the white boys in his high school. Unwilling to accept second-class status passively, he took it upon himself to desegregate the pool by attending the white students’ class. But because he was unable to swim, Bob would enter the shallow end of the pool and cling to the side for the entire class period — alone, since the white boys would not use the pool with him. After attending Lincoln University and Howard Law School and obtaining a master’s degree from Columbia Law School, Bob was inducted into the armed services early in World War II and became a member of the Army Air Corps. Shared danger and hardship were not, however, accompanied by social equality, as he learned when the bartender of the officers’ club at an air field in Louisiana initially refused to serve him. Once again declining to accept unequal treatment, Bob demanded — and received — the service accorded other officers.

Given his fervor about racial injustice, Bob could well have become a social radical. But, as implied by the title he later chose for his autobiography — A Matter of Justice — he sought to effect change by working within the legal structure. Accordingly, after the war, he joined the legal staff of the NAACP, where he worked with Thurgood Marshall on Brown, taking primary responsibility for assembling the social science evidence that ultimately persuaded the Supreme Court that separate could never be equal. He won 20 of the 21 cases he argued in that Court and ultimately was named general counsel of the NAACP. Bob’s departure from the NAACP was characterized by the same adherence to principle as his stand against discrimination. An attorney on his staff, Lewis Steel, wrote an article in the New York Times Sunday magazine entitled “Nine Men in Black Who Think White,” which was a provocative critique of the Supreme Court’s record on civil rights. After the article was published, and without prior notice to Bob, the NAACP board of directors fired Steel. Bob considered the board’s action wholly unjustified, and when it would not rescind its decision, he resigned and took a job in private practice.

Despite Bob’s credentials as an attorney, including his stint representing clients as partner in a law firm, his nomination to the district court bench in 1972 was met with skepticism by some. At his confirmation hearing, for example, one senator asked if he could be fair to white litigants. Another, apparently concerned about the supposedly constricted experience of public interest lawyers, asked if he knew anything about admiralty law. Bob’s answers were evidently deemed satisfactory, and he was confirmed.

Some litigants, however, remained suspicious of Judge Carter’s background as an advocate. On one occasion, counsel for the defendant in a Title VII case asked the Judge to recuse himself on the theory that, having been a civil rights litigator, he would have at least a subconscious bias against the defendant. Judge Carter denied the request peremptorily, noting that there was no more basis for recusal in that case than there would be for a judge with a private firm background to remove himself from every securities case.

On the bench Judge Carter meted out the same fair treatment he had always demanded from others. And, while he maintained his passion for civil rights, his decision in any given case adhered strictly to the law. I had the great good fortune to serve as one of Judge Carter’s law clerks from 1978 to 1979. I expected, somewhat naively, that his judicial decision making would hew strictly to the values and priorities he had espoused as an advocate; I was wrong. At one point during my tenure, it so happened that my co-clerk and I were asked to work on two major cases that had just become ripe for decision. One was a Title VII class action challenging practices of the New York City Police Department that allegedly discriminated on the basis of race. The other involved novel issues under Section 13(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. I drew the short straw and was assigned the securities case. It was a revelation to me that Judge Carter devoted equal time and attention to each case, demonstrating to us that what was important was a just result for each litigant, regardless of one’s personal views of the relative importance of the issues involved.

While Judge Carter’s experiences did not skew his commitment to the law, they gave him insight into how that law might best be applied in some of the cases that came before him. One example is United States v. Chimurenga, a criminal case involving a group of black activists who became known as the “New York Nine.” The defendants had amassed firearms and preached revolution against the government, which they perceived as oppressing minorities, and so were tried as terrorists. When the jury returned guilty verdicts only on charges of weapons possession, Judge Carter exercised his discretion to impose sentences of community service. In his view, the defendants had experienced real injustice but had chosen the wrong means to effect change. Only one of the defendants is known to have later committed criminal acts.

This is not to say that Judge Carter’s experience led him to be “soft on crime.” To the contrary, he was far from a libertarian when it came to enforcement of the drug laws, since he believed that narcotics undermined minority communities and impeded progress toward equality.

While Judge Carter was careful to follow the law in his judicial decision making, he also recognized that he had a role in shaping it. If he was issuing a determination on a subject that he felt passionately about and where the precedent was aligned with his values, he might write a more sweeping opinion. On the other hand, if the law dictated a result contrary to his beliefs, he would take a narrower approach, perhaps leavening the opinion with dicta suggesting why the precedent he was bound to follow should be reconsidered.

Outside the courtroom, Judge Carter could be less restrained. In 1995, he received the Emory Buckner award from the Federal Bar Council for his contributions to justice. In acceptance speeches for such awards, honorees generally heap praise on their colleagues on the bench, the members of the bar, and the justice system generally. Not Judge Carter. While acknowledging the progress that had been made in dismantling legally sanctioned discrimination, he used the platform he had been provided to argue that the legal profession had failed to do all that was within its power to achieve social and economic equality.

What is remarkable about Judge Carter, then, was his ability to reconcile his deeply held values and experience as a zealous advocate for change with his role as a dispassionate jurist operating within the strictures of the law. That he was able to do so with grace and integrity made him a model and an inspiration for lawyers and jurists alike.