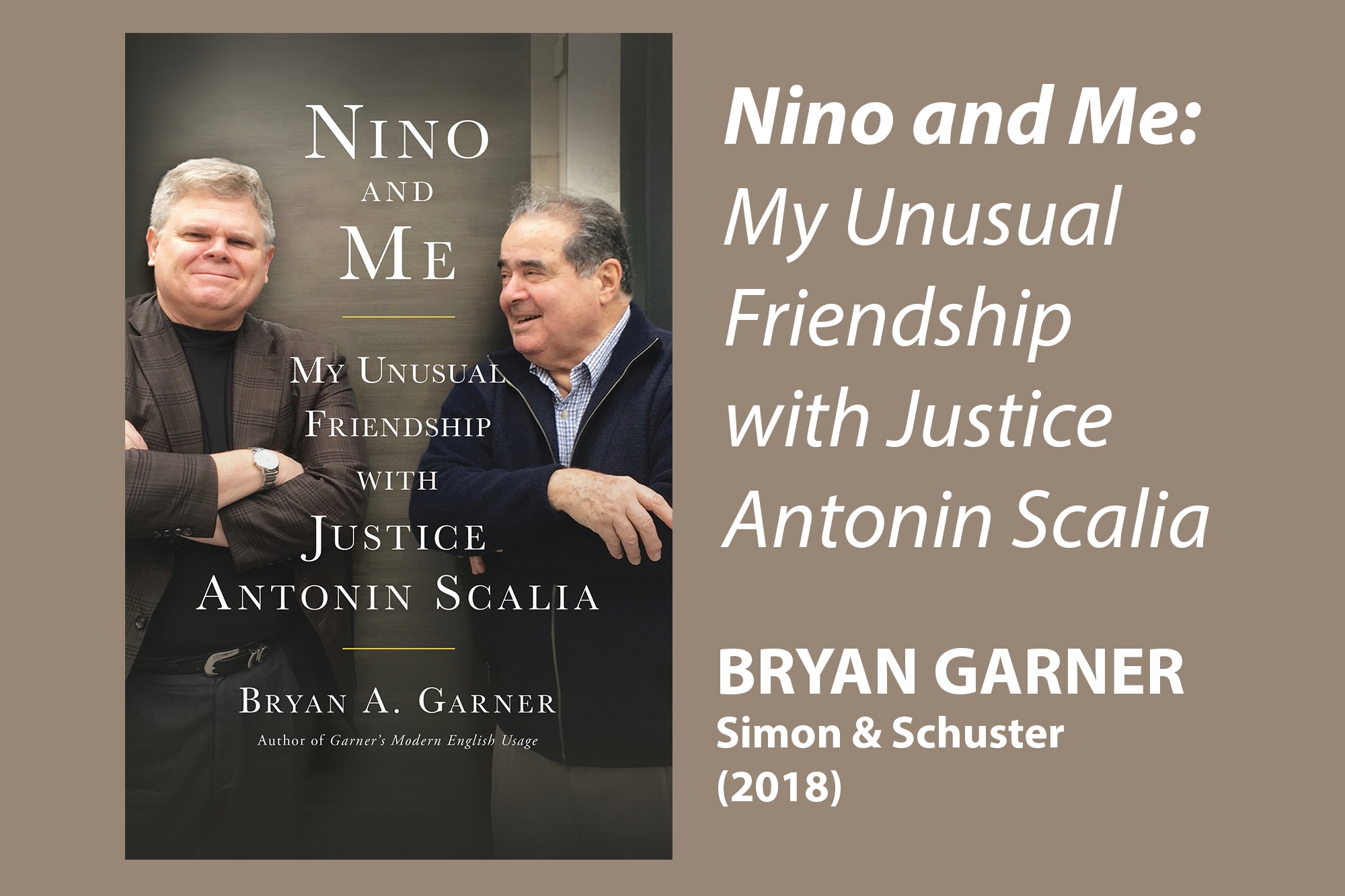

Collaborative writing can be a delicate endeavor for many judges, especially when collaborating with someone who is not a judge. Bryan Garner’s newest book, Nino and Me, offers not just an intimate portrait of Garner’s friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia, but also an insightful look at the challenges of writing with someone else.

Written as a friend’s tribute to Justice Scalia, Nino and Me focuses on the writing process behind the two books Garner and Scalia wrote together: Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (West 2012), and Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges (Thomson West, 2008). Interesting stories about their friendship abound: Garner recounts tales involving Justice Scalia performing at Garner’s wedding, a trip the two took together to the Far East, and time spent together with their families. He also recalls cooking eggs for Scalia (and their disagreement as to how to properly cook eggs); getting haircuts together; and details of their exercise routines.

Garner also offers his insights into Scalia’s judicial philosophies and perspectives, covering Scalia’s thoughts on topics such as the difference between textualism and originalism; the role “justice” should play in judicial decisions; judicial appointments; originalism; separation of powers; and more.

But perhaps the most unexpected and useful insights of the book are Garner’s thoughts on what it takes to successfully collaborate with a coauthor. Of course, most legal professionals know that Garner is a terrific writer, and he knows well that one of the most important parts of luring the reader is the “hook.” Garner writes that he had the ideas and formats in mind for both books long before he had Scalia on board. But he knew Scalia would be the perfect hook for attracting readers. Of course, Garner acknowledges that he soon became the “sidekick,” not the “superstar,” emphasizing the point that sometimes one must yield to the “bigger player” in order to ensure a successful collaboration.

Garner suggests that, regardless of the imbalance in reputation between the writers, it was important that they find common ground. Both Garner and Scalia described themselves as “snoots,” people who care intensely about words, usage, and grammar. Although their political philosophies were on the opposite ends of the spectrum, both were textualists and orginalists, which provided a foundation for their writing. These commonalities were key throughout their collaborative writing process and obviously contributed greatly to their successful partnership.

Both authors considered their books to be 50-50 collaborations, so much so that it can be difficult to know who wrote what. They pulled off this seamless presentation by establishing a thoughtful writing process, including initial talks, negotiations, and drafting of contracts through to the final editing and publishing of the books. Beginning the collaborative process by drafting an outline and a table contents, he suggests, was a key step to setting the organizational framework for the writing process.

As seamless as the end products are, Garner describes their writing process as time consuming and difficult. Reading Law took over three years to write, and the two authors went through at least 250 drafts before final publication. They spent countless hours writing and editing in Scalia’s chambers and Garner’s office, all while working “day jobs” as a U.S. Supreme Court justice and a prominent writer and lecturer.

A thoughtful writing process and many hours of work, however, did not prevent the two from arguing. One argument over word processing programs — they used different programs, and neither wanted to give up his preferred software — nearly derailed a book. They also disagreed about the use of footnotes, gender-neutral language, and contractions, among other things. Thankfully, they were able to resolve their issues, and their compromises paid off in the form of two highly regarded legal texts.

One last story seems worth sharing: Before the two launched their now famous partnership, Garner had serious doubts about asking Justice Scalia to write with him. Garner recalls his own father chastising him for thinking that he was in the same league as Scalia. Garner even tried to stop the letter he had written to Scalia to invite him to collaborate. Fortunately, the letter went through and opened the door to Reading Law, now widely regarded as the authority on the legal interpretation of texts. Garner’s experience should inspire those who have an idea but may be afraid to take action and encourage the use of collaboration to complement one’s skills with those of a co-author.

Writers interested in the collaborative writing process will find Nino and Me helpful, and judges will find it useful for its insights on the process and pitfalls of collaborative writing. And its light-hearted look at a unique friendship between two legal luminaries makes Nino and Me a fun read for anyone interested in Scalia’s life on and off the bench.