Judging AI: How U.S. Judges Can Harness Generative AI Without Compromising Justice

Vol. 109 No. 2 (2025) | Communicating to the People | Download PDF Version of Article

In a voting-rights trial with thousands of pages of evidence, generative AI tools offered a glimpse of how technology might ease the judiciary’s heaviest burdens.

E-discovery tools that harness the power of artificial intelligence (AI) assist attorneys somewhat regularly.1 But my recent experience presiding over a bench trial in La Union Del Pueblo Entero v. Abbott showed me that generative AI (GenAI) can help judges in several crucial ways that go far beyond discovery.

La Union Del Pueblo Entero was a consolidated action brought by advocacy groups, voters, and an election official challenging two dozen provisions of an omnibus election law enacted in Texas in 2021, known as S.B. 1, under various federal civil rights statutes and the U.S. Constitution. In all, there were approximately 80 witnesses (both live and by deposition testimony), nearly 1,000 exhibits, and more than 5,000 pages of trial transcripts.

This case provided an opportunity to evaluate how GenAI might help a judge in a complex and document-intensive case. This article explores how GenAI can help locate documents and summarize witness testimony, whether GenAI tools are currently capable of completing a rough draft of a judicial opinion, and how GenAI can review party submissions.

Locating Documents: Saving Trees and Cutting Time

The first challenge facing my chambers was simply how to locate the exhibits and relevant portions of testimony as we began researching and drafting findings of fact and conclusions of law (FFCL).

While the federal court’s electronic case filing system (ECF) permits full-text searches of docket filings, its functionality is limited. First, it relies on keyword search, which tends to be both over- and under-inclusive. Second, many documents filed on ECF have not been run through optical character recognition (OCR) software, rendering them unsearchable. Third, ECF searches do not permit judges to limit their queries to specific documents on the docket or to search documents that have been submitted to the court but not yet filed. Thus, a search for a party name, for example, would likely turn up every document filed in the case — not a particularly helpful exercise.

I teach an e-discovery law school course, and over the past 10 years, many vendors have graciously provided my students with access to their review platforms. I give my students requests for production and require them to use the relevant platform to provide the number of “hits” they believe are responsive. Given the difficulty my chambers would have in locating relevant exhibits, I immediately thought of turning to an e-discovery provider to ingest, index, and grant me access to a review platform that I could use to locate documents (or portions of documents) needed during the drafting process.

Merlin,2 an e-discovery vendor, agreed to help me, and — after the court’s IT department vetted the company for cybersecurity concerns — we uploaded about a thousand documents representing all the trial testimony, admitted exhibits, the parties’ briefings and proposed FFCL, and my earlier orders in the case to a secure site created specifically for our project.

Merlin’s OCR and integrated keyword and algorithmic search capabilities (Search 2.0) allowed my chambers to quickly locate key documents and testimony without crafting complicated searches. Like many e-discovery tools I have used, Merlin permits users to tag documents by relevant fields.

Given the evolution of GenAI in recent years, I was interested in testing out other uses for these tools in my chambers, including tasks — such as summarizing evidence and drafting factual findings — and reviewing our work product.

One note, however: Judges and attorneys considering using these GenAI tools should be cautious in uploading any data that is confidential, privileged, or otherwise contains sensitive data (e.g., financial or health information). In particular, users should ensure that the provider’s large language model (LLM) does not use any nonpublic data to train its system and that the provider has adequate cybersecurity measures in place.3

Summarizing Text: Generating Overviews of Witness Testimony

GenAI has a unique ability to summarize text data. Although GenAI summarization can struggle with some types of information, judges and lawyers may find GenAI to be useful for analyzing trial and deposition testimony. Deposition and transcript summaries are a standard way to extract, condense, and organize information from testimony that may be spread over the course of hundreds — or thousands — of pages and multiple days of examination. While useful, they can be time-consuming (and expensive) to create and, depending on how they are structured, can produce inflexible results.

To conduct this task manually, the judge or lead counsel must determine how the transcript will be summarized (e.g., chronologically, by witness, or by topic). Then, a more junior attorney or legal assistant must locate the portions of the transcript they intend to summarize, typically by running keyword searches against transcripts. Finally, of course, they read and summarize the portions of the testimony they identified through their keyword searches, including pin cites to the pages and lines of the transcript along the way.

Even high-quality manual summaries can be cumbersome to use during the writing process, because, like the underlying transcripts themselves, they are static. For example, an attorney may find it difficult to quickly identify testimony about a certain topic if the summaries have been organized by date or witness. At the same time, because the purpose of the summaries is typically to help attorneys locate relevant testimony in the transcript — to be quoted or cited in briefing — summarization itself often represents the first step in a tedious, iterative process that takes attorneys from transcripts to summaries and back again (and again).

GenAI systems deploying retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), including Merlin’s, are particularly well-suited to summarizing transcript testimony because they mirror the manual process, albeit with much greater speed, power, and agility. RAG reduces hallucination by deploying an LLM’s language capabilities to answer questions in the context of a constrained data set through a two-step process:“(1) retrieval and (2) generation.”4

When a user submits a question to a RAG system, it first searches a set of documents defined by the user to find the most relevant passages. In the second step, generation, the system provides the relevant documents and original query to an LLM, which uses both inputs to generate an “open-book” answer.5

As an experiment, I compared my staff’s summarization skills (and speed) against Merlin’s. I asked my law clerks and interns familiar with the case to summarize portions of the trial testimony and keep track of the time it took them to review the testimony and prepare a summary (with relevant citations to the record).

Many resources report that it takes an experienced attorney or paralegal one hour to summarize about 25 pages of deposition testimony. Suffice it to say, it took my law clerks and interns much longer to summarize the testimony in my case (which I attribute to their desire to be exacting in their work).

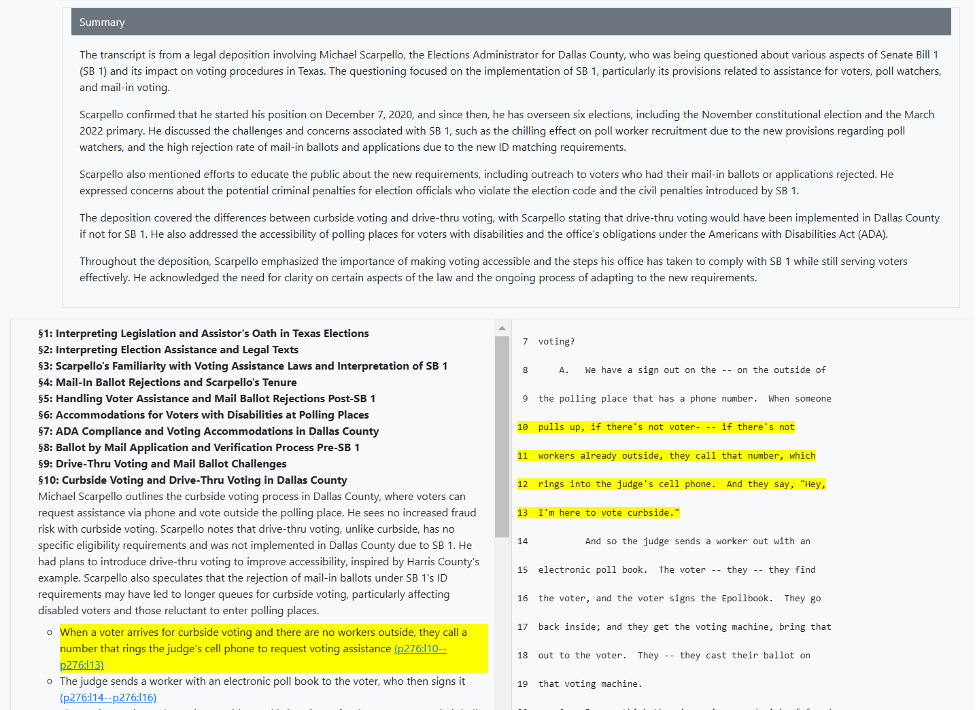

Running a simple prompt requesting a summary of the process for curbside voting in Texas, Merlin produced a comprehensive response within seconds, pulling from both deposition and trial testimony and across multiple witnesses. (In fairness to my intern, I asked him to produce a summary of the process based on testimony from a single witness on a single day of trial.) The two responses follow below.6

Intern’s response: The curbside voting process begins with the press of a button, which calls an election worker to the vehicle. Tr. at 704:15–17. Often, a brief wait ensues before an election worker is available. Tr. at 705:4. The election worker then takes the voter’s identification (and that of any assistor) and authenticates the voter’s registration status before disbursing the ballot materials. Tr. at 704:4–8. A private assistor must sign the Oath of Assistance under S.B. 1. Tr. at 709: 14–18. As soon as a voting machine becomes available, the election worker must wheel it out to the vehicle and position it in front of the voter, so that the voter (and, if applicable, a private assistor) can read the options on the ballot and make his selections on the machine. Tr. at 705:21–24, 706:7–13, 706:21–24, 707:6–7. The entire process may take upwards of 45 minutes. Tr. at 707:24.

Merlin’s response: Curbside voting in Texas is a process designed for voters who are physically unable to enter the polling place without assistance or at the risk of injuring their health. An election officer delivers a ballot to the voter at the entrance or curb of the polling place if curbside voting is requested. Tr. at 827:4-12. Curbside voting is available at every polling location across Texas. Tr. at 1152:8–13.

The process involves a voter signaling for assistance, after which an election worker verifies their ID, brings the equipment out, the voter marks their ballot, and the worker takes the ballot inside to scan it. Tr. at 1152:19–1153:3. In some cases, when a voter arrives for curbside voting and there are no workers outside, they can call a number that rings the [election] judge’s cell phone to request voting assistance. Scarpello Dep. at 276:14–19. The [election] judge then sends a worker with an electronic poll book to the voter, who signs it, and the worker retrieves the voting machine and brings it out for the voter to cast their ballot. Scarpello Dep. at 276:14–19.

All election workers in Harris County are trained on curbside voting, indicating that it is a standard practice. Tr. at 1152:14–16. The security of curbside voting is considered to be on par with that of in-person voting inside the polling place, as the procedure is the same whether conducted inside or outside the building. Scarpello Dep. at 276:20–25.

It is important to note that curbside voting is distinct from drive-through voting, which was offered in Harris County during the November 2020 election. Drive-through voting allowed voters to pull up in their vehicle, mark their ballot at the machine outside, and then deposit their ballot into the scanner themselves, without the ballot ever leaving the voter’s sight. Tr. at 1153:4–1154:17. However, drive-through voting . . . was offered [to all Harris County voters in November 2020] to provide more accessibility and opportunities for people to vote. Tr. at 1154:18–1155:5. Curbside voting, on the other hand, is specifically for eligible voters who meet certain criteria and is a method that has been offered by all counties across Texas. Tr. at 1236:22–1237:14, 1237:21–25.

Of course, the fact that a GenAI tool creates a summary at a fraction of the time (and likely cost) of human-generated summaries must be balanced against the accuracy and usefulness of the GenAI summaries, which humans must ultimately evaluate. In my case, I used the summary as a launching point to locate the relevant evidence. The intern’s summary was a bit more focused, while Merlin’s response was slightly more general. Had the goal been to incorporate the summary wholesale into a draft opinion, the intern’s work would have proved more useful.

Like other programs I have reviewed, Merlin enables users to evaluate the accuracy of its summaries by providing citations to supporting evidence with links to the original source documents. Thus, in instances where the summary seemed a bit shallow, a mere click on the record link allowed my chambers to quickly find additional details and context. Merlin also allows users to download (or copy and paste) both responses to prompts and the AI-generated summaries of the underlying documents.

Fig. 1. Sample response to prompt, with links to supporting testimony.

Fig. 2. Sample deposition summary, with headings and links to supporting testimony.

Drafting: First Passes at Orders

After test-driving GenAI’s summarization capabilities, I was curious about its ability to analyze and make judgments about the information stored in the review platform. I asked Merlin to draft findings of fact7 on one of the causes of action in the election case.

First, I did not (and will not currently) use any GenAI product to draft orders or FFCLs ultimately filed in a case. I ran the prompts in Merlin discussed below only after my chambers had published the FFCLs on the plaintiffs’ challenges under the First Amendment and Section 208 of the Voting Rights Act in the traditional manner.8

Second, I do not advocate that GenAI be used as a substitute for judicial decision-making, for many reasons. A GenAI response might be partially or even completely inaccurate. A judge may unintentionally become “anchored” to the GenAI’s response — sometimes referred to as automation bias, a phenomenon in which humans trust GenAI responses as valid without validating the results. Similarly, a judge might be influenced by confirmation bias, where a human accepts the GenAI results because they align with the beliefs and opinions already held.

That said, I do not doubt that GenAI tools can be used to assist judicial officers in performing their work more efficiently. A GenAI tool could also be used after a draft of an order or opinion is completed to verify or question the draft’s accuracy, and confirmation bias can occur without the use of an AI tool.

Prompt 1: Findings of Fact on a Single Theory of Liability

In my first test, with assistance from the Merlin team, I prepared a prompt seeking findings of fact and conclusions of law on a single theory of liability: that a restriction on certain “compensated” canvassing activities “in the presence of” mail-in ballots (the canvassing restriction) is overbroad and chills free speech in violation of the First Amendment. I requested a legal opinion that would identify the parties, outline the procedural history of the case, assess the impact of the canvassing restriction, discuss the parties’ standing, and evaluate the merits of their challenge.

Merlin used an AI chatbot app called Claude 3.5 Sonnet in two capacities: first, to produce 1,685 summaries (reflecting the entire universe of documents uploaded to the platform) and then to produce a 12-page narrative response to my prompt based on the summaries.9 The results of the first test quickly revealed the first insight of my experiment: GenAI is not yet ready to replace judges (phew!). As the saying “garbage in, garbage out” suggests, its outputs are only as good as its inputs, both in the quality of information sources being mined and the prompts submitted to the platform.

To begin, the results were overbroad. For example, although my prompt requested information about the canvassing restriction, the answer discussed several other provisions of S.B. 1 being challenged in the litigation, as well as parties who were not challenging the canvassing restriction, including some who had been dismissed from the case entirely.

Of the dozen pages that Claude 3.5 Sonnet produced, only two or three were relevant.

To the extent they were relevant, the analysis included within them was often quite superficial. For example, in its discussion of standing, the answer stated, “Many organizational plaintiffs have demonstrated standing by showing (a) Diversion of resources to counteract S.B. 1’s effects, (b) Chilling effect on their activities, (c) Concrete changes in operations, [or] (d) Harm

to their members’ voting rights.” These generic descriptions of the bases for organizational standing did not speak to the question at hand — which, if any, of the plaintiffs had standing to challenge the canvassing restriction specifically. Even more targeted responses were too vague to provide a clear basis for standing. A statement that “Mi Familia Vota express[ed] concerns about potential accusations of vote harvesting during legitimate voter outreach activities” does not identify the nature of those activities or whether the organization has decided to modify or cease its outreach activities.

Thus, to effectively use GenAI as a tool in judicial opinion writing, judges and their staffs will still need to exercise judgment:

- Judges must still be familiar with the factual and legal disputes at the hearts of their cases to develop prompts that yield relevant and accurate results.

- Judges also need to consider the limitations of the specific tool being used and the nature (and scope) of the evidentiary record.

- Finally, as discussed above, judges must evaluate the relevance, accuracy, and limitations of the results.

Based on the initial results, I knew I had to make some changes to my prompts because of the case, the underlying documents, and Merlin’s capabilities.

For example, I realized that I should limit my request to factual findings rather than asking Merlin to prepare legal conclusions, for a few reasons.

First, because Merlin is not connected to a legal database and is instead drawn from a closed universe of documents, it was not designed to produce legal analyses.

In this case, the parties disagreed about the legal standard for evaluating the First Amendment challenge. The plaintiffs argued that strict scrutiny should apply, while the defendants proposed a lower standard under the Anderson-Burdick line of cases.

Although Merlin and I ultimately both applied the same standard — strict scrutiny — I suspect that Merlin defaulted to the plaintiffs’ proposed standard simply because they filed more briefs than the defendants. Differences in quantity may be relevant for the purpose of analyzing propensity and/or the weight of the evidence, but the quantity of briefing in support of a given legal standard obviously does not affect which standard judges should apply (and may not even reflect the weight of authority).10 Moreover, while the trial record is static following the close of evidence, legal standards can change during the course of litigation — and did in this particular case. In any event, for this project, I was interested in testing GenAI’s ability to analyze and synthesize evidence to make factual findings — its ability to act as a jury, not a judge — because making fact findings often represents the most time-consuming and resource-intensive part of a judge’s work following a bench trial.

Second, given certain limitations in the evidentiary record, it also became clear that, to ensure relevant results, the prompt should center on the factual findings necessary to support the plaintiffs’ specific legal theories rather than ask about the legal theories themselves. In other words, I had to bake some judgments and assumptions about the facts and claims into my prompt.

For example, while my initial prompt asked Merlin about First Amendment challenges to the canvassing restriction, the response addressed facts bearing on all kinds of claims asserted by the plaintiffs (e.g., racial disparities) and discussed other portions of the law (e.g., an ID-number matching requirement for mail voting). I expect that these responses appeared because, at trial, many witnesses for civil rights groups who testified about the canvassing restriction’s chilling effect on their speech were also asked about its effects on specific groups of voters and about the impact of other provisions of the election code at issue in the litigation.

With good reason, attorneys did not constantly reference the applicable theory of liability in each of their questions at trial. Not only would it have been an unbearably awkward form of questioning, but many questions were also intended to elicit responses relevant to multiple claims. And, in addition to potentially confusing lay witnesses, asking them to describe how the canvassing restriction impaired their First Amendment rights would have required them to draw improper legal conclusions. Instead, witnesses were asked questions about the effect that the canvassing restriction had on their interactions with voters (i.e., facts relevant to their overarching legal theories). It is unsurprising, then, that the results of my initial prompt were both under- and over-inclusive to a certain degree — I had asked Merlin to draw inferences and connections based on legal reasoning not made explicit anywhere in the trial transcript or evidentiary record. Accordingly, iteration — refining and optimizing prompts — was necessary.

Prompt 2: Findings of Fact Only, With Specific Instructions

My revised prompt:

Assume you are a United States district judge presiding over a bench trial concerning First Amendment free speech and overbreadth and Fourteenth Amendment due process challenges to the “vote harvesting ban” under Texas Election Code section 276.015, enacted as Section 7.04 of the Texas Election Protection and Integrity Act of 2021 (commonly known as “S.B. 1”).

Please prepare detailed findings of fact concerning plaintiff organizations’ First Amendment free speech and overbreadth and Fourteenth Amendment void-for-vagueness due process challenges under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52, based on a comprehensive review of the trial testimony, exhibits, and briefs submitted by all parties. Your findings should address the following key areas:

1. Challenged Provisions

Describe Section 7.04 and define it as the “Canvassing Restriction.” In your response, please refer to Section 7.04 of S.B. 1 as either Section 7.04 or the “Canvassing Restriction.”

2. Procedural History

Outline the chronology of the First Amendment and challenges to Section 7.04 from initial filing to the conclusion of the bench trial. Include key motions, rulings, and any significant pretrial events.

3. Parties

Provide the following information about the parties:

Plaintiffs: Identify and describe the following plaintiffs in separate paragraphs with bold headings: League of United Latin American Citizens – Texas (LULAC), Texas American Federation of Teachers (AFT), Texas Alliance for Retired Americans (TARA), La Union Del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), and Mexican American Bar Association of Texas (MABA).

Defendants: Identify and describe the following defendants: the Texas attorney general, the Texas secretary of state, and the district attorneys of Travis County, Dallas County, Hidalgo County, and the 34th Judicial District, including their respective authority under Texas law to enforce, investigate, and prosecute crimes under the Texas Election Code and evidence of their willingness to do so, with special attention to “vote harvesting” crimes.

4. Difficulties and Confusion in Interpreting Section 7.04

Give examples of the difficulties and confusion trial witnesses (including voters, organizational representatives, canvassers, assistors, election officials, and state officials) have experienced in interpreting Section 7.04, including:

The meaning of “physical presence” and “compensation,” and

Whether the Canvassing Restriction prevented canvassers from providing mail-ballot voting assistance.

Make sure to cite specific testimony by individuals wherever possible regarding these issues, providing as many citations to trial testimony as possible.

5. Section 7.04’s Impact on Plaintiffs’ Free Speech and In-Person Voter Outreach Efforts

Provide factual conclusions showing how Section 7.04 has limited the plaintiff organizations’ free speech and in-person voter outreach efforts, including canvassing, hosting election events, and providing voter assistance.

Make sure to cite specific testimony by individuals wherever possible regarding these issues, providing as many citations to trial testimony as possible.

In response, Merlin produced a 10-page written response — with impressive results.

While the response to my first prompt produced two vague descriptions of the “chilling effect” of the canvassing restriction (“Organizations like Mi Familia Vota express concerns about potential accusations of vote harvesting during legitimate voter outreach activities.”), the second report provided specific and accurate examples of voter outreach activities that had been impaired:

- OCA-Greater Houston (Organization of Chinese Americans) canceled candidate forums, limited involvement in co-sponsored events, and shifted to virtual formats for meet-and-greets.

- Organizations have reported difficulty in recruiting volunteers willing to provide voter assistance due to concerns about criminal penalties.

- FIEL (Familias Inmigrantes y Estudiantes en la Lucha) discontinued its “caravan to the polls” activities due to concerns about potential legal consequences under S.B. 1.

- LULAC has scaled back or stopped completely its voter assistance programs in some areas due to fear of prosecution.

- Texas AFT has significantly reduced its canvassing efforts, shifting to alternative outreach methods like texting, letter campaigns, and phone calls.

- TARA stopped accepting or setting up tabling invitations during the period when mail ballots are out.

- OCA-Greater Houston has stopped providing voter assistance, including language assistance to Chinese-speaking voters, due to concerns about S.B. 1.

- Unlike the response to my first prompt, the second report also described witness testimony explaining the basis for the canvassing restriction’s chilling effect on political speech — its broad and vague terminology:

- Keith Ingram from the Texas Secretary of State’s Office stated that both the voter and the harvester must be looking at the ballot together for an interaction to be considered “in-person,” but could not provide a specific distance for what constitutes “in-person interaction.”

- Grace Chimene from the League of Women Voters expressed concern that even small gestures like offering tea, coffee, or parking assistance could be considered compensation.

- Deborah Chen from OCA-Greater Houston expressed confusion about whether providing water bottles or T-shirts to volunteers could be considered compensation.

- Jonathan White, a state official, acknowledged that further research would be needed to determine if things like gift bags or meals count as compensation.

Reviewing Judicial Drafts and Party Submissions

While conducting tests with Merlin, I had an opportunity to try another GenAI tool, Clearbrief. Like Merlin, Clearbrief allows users to upload sources to a secure site devoted to a specific project.

Employing OCR and search technology as Merlin does, Clearbrief enables users to quickly find information in the underlying documents. While Merlin functions as a separate site, Clearbrief operates through a Microsoft Word add-in. This feature lets users extract text from the record and paste it directly into a draft Word document (automatically including a record citation).

Fig. 3. Copying text from source PDF into draft opinion.

Clearbrief can generate timelines, topic tables, and deposition summaries based on uploaded documents, though it does not produce prompt-based summaries of the underlying information. Clearbrief also has access to legal resources available on LexisNexis and in the public domain, which allow it to score how well sentences in a brief or opinion are supported by the cited legal (or factual) authority.

Fig. 4. Clearbrief cite-checking, with link to the relevant legal authority.

Clearbrief’s combined capabilities have allowed my chambers to prepare timelines of case events and verify the accuracy of briefs and record citations, which can be helpful during status conferences and hearings. They have also helped my chambers review and cite-check drafts of my opinions before they are published.

The Last Word

The voting rights case presented a unique opportunity to assess the current state of GenAI proficiency at various tasks and to experiment with ways to improve its performance. Rather than treating all platforms as one-size-fits-all, courts considering adding GenAI to their toolboxes should determine whether an à la carte approach would better serve judges’ needs in some cases.

Merlin’s summarization capabilities may be more helpful for large-scale, complex, fact-intensive cases — as it was in this one — since each project requires creating a new and separate secure site. Yet Clearbrief’s technology may be more helpful for some of the everyday work of the judiciary, such as preparing for status conferences and hearings, reviewing briefs, and cite-checking opinions.

A few widely publicized misuses of AI in the legal profession have caused moral panic in some circles (including the judiciary), rendering “AI” a four-letter word. While concerns about cutting corners arise out of legitimate problems — including systemic resource disparities and individual bad apples — much of the ire and fear directed at the use of AI is, in my view, misplaced. As I like to point out, attorneys have been hallucinating cases since long before AI.

To be sure, there are bad and lazy (and overworked) attorneys in the world. But refusing to deploy GenAI technology in the judiciary will not stop those attorneys from citing cases that do not exist or supplying faithless summaries of a factual record. It will only ensure that the judicial task of detecting such misdeeds is unnecessarily cumbersome.

There are also bad and lazy (and overworked) judges. Refusing to deploy GenAI technology in the judiciary will not protect the litigants who come before them from the deficiencies in their chambers. While some have expressed concern that permitting judges and clerks with access to AI features of legal databases will use it as a substitute for legal research, the same judges and clerks could easily (without AI) substitute the prevailing parties’ briefing for legal research. In other words, uncritically copying and pasting is not a sin exclusive to AI.

Moreover, to the extent that individual judges are willing to uncritically accept GenAI results, that decision (and accompanying risks to their reputations and appellate reversal rates) are better left to judges themselves rather than court administrators. Given judges’ broad authority to make significant and far-reaching — sometimes even life-or-death — decisions in the U.S. legal tradition, there is some irony in the suggestion that they cannot be trusted to make prudent decisions about whether and how to use a technological tool to support their work.

As my experiments demonstrate, the effective use of GenAI to support judicial work will still require attention to detail and good judgment, both in crafting prompts and using the results. But GenAI can be a helpful tool for improving judicial efficiency, cutting out much of the tedious legwork of locating, collecting, and describing facts in the record and arguments by the parties.

GenAI tools can be readily used by judges in preparation for initial scheduling conferences by quickly generating timelines and summaries that allow for more meaningful conferences with litigants about, e.g., the appropriate scope of discovery, the possibility of alternative dispute resolution, and even the viability of their respective legal theories. GenAI can also be used to help prepare judges for hearings on motions to dismiss or motions for summary judgment. The state of GenAI tools is such that, at the time of our testing, they could not create judicial opinions or substantive orders, but with responsible use, they can assist judges in more efficient adjudication of the cases before them. The GenAI landscape is rapidly shifting, of course, and as existing platforms continue to evolve and new products emerge, they may be able to generate something closer to a final product.11 Still, there’s no substitute for good judgment.

Xavier Rodriguez is a U.S. district judge for the Western District of Texas and a 2023 graduate of Duke Law School’s Master of Judicial Studies program.

1 My thanks to my career law clerk, Caroline Bell, for her assistance as we explored AI tools for chambers use, and for her contributions to this article. My thanks also to Allison H. Goddard, U.S. magistrate judge for the Southern District of California, and Maura Grossman, research professor at the University of Waterloo, for their review of this article and their suggestions.

2 For more information on these products, see generally Merlin Search Technologies (2024), https://www.merlin.tech; Clearbrief (2025), https://clearbrief.com/. I do not endorse any e-discovery or AI product. References to any product are solely for illustrative purposes as to what certain products can do and what limitations may arise.

3 The American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants has defined criteria for managing customer data based on “five Trust Services Criteria . . . security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality, and privacy.” Danielle Marie Hall, What Is Candle AI?, ABA L. Prac. Mag. (July 3, 2025), https://duke.is/y/m8z3. Many GenAI commercial providers contractually agree that they will not use prompt information for training. All users should review terms of service before using a product.

4 See Varun Magesh et al., Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools, 22 J. of Empirical Legal Stud. 216, 219 (2025).

5 Id.

6 These summaries have been lightly edited for clarity and consistency.

7 Merlin is not able to generate conclusions of law since it is not trained on U.S. legal authorities.

8 La Union del Pueblo Entero v. Abbott, 751 F. Supp. 3d 673 (W.D. Tex. 2024) (containing the FFCLs regarding First Amendment challenges). Although this order was already published by the time I tested Merlin’s GenAI capabilities, I did not upload it to the secure site before testing in order to avoid introducing bias to the testing.

9 Merlin used Claude 3.5 Sonnet at the time of testing but is now equipped with a variety of the leading GenAI models.

10 Of course, even GenAI tools with access to legal databases like Westlaw or LexisNexis are merely starting points for judges and clerks during the legal research process and not a substitute for judicial analysis. That is, even if GenAI accurately identifies the weight of nonbinding authority, I may not be inclined to follow it. See also Magesh et al., supra note 4, at 226 (noting that GenAI models designed for legal research have difficulty grasping hierarchies of legal authority).

11 Since conducting these experiments, I have also had the opportunity to test Westlaw’s AI-assisted research tool for legal research, CoCounsel, and a GenAI platform designed to support judges and their judicial staff called “Learned Hand,” which has recently been adopted by the Michigan Supreme Court. See Press Release, Learned Hand, The Mich. Sup. Ct. Conts. with Learned Hand for Purpose-Built Jud. AI, Nat’l L. Rev. (Aug. 11, 2025), https://duke.is/r/w5nt.