A Matter of Style: Perceptions of Chief Justice Leadership on State Supreme Courts With an Eye Toward Gendered Differences

by Charlie Hollis Whittington and Mikel Norris

Vol. 102 No. 2 (2018) | Rights That Made The World Right | Download PDF Version of Article

Although most research on court leadership still focuses on the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, researchers are increasingly interested in state supreme courts, and with good reason. State supreme courts provide a more diverse institutional setting for understanding court leadership than the U.S. Supreme Court.1 Different states have different norms and rules. Some state court systems are consolidated while others are not. Some states give opinion-assignment power to their chief justices. Some do not. States differ in how they choose their chief justices and the length of terms they serve. Finally, different states choose their panels of justices in different ways. Some state courts hear every case en banc, whereas others assign cases to smaller panels of justices. These differences and more make understanding how the justices on these courts — and chief justices in particular — believe their courts should be managed interesting and relevant, both for scholars and judicial leaders.2

The purpose of this analysis is to examine and analyze leadership styles, skills, and attributes on state supreme courts. This area of research is growing in academic study, as more scholars — particularly in political science and public administration — are examining how our political institutions are run, rather than focusing only on the politics that take place in those institutions.3 We are particularly interested here in discerning if there are differences in leadership style preferences between men and women on state high courts. Many bemoan the dearth of women in leadership in American politics; however, women have been incredibly successful in obtaining the position of state chief justice. Over half of the state chief justiceships were held by women as recently as 2014. This fact alone should interest scholars and pundits who study gender and leadership. In this article, we attempt to shed light on two specific questions pertaining to court leadership. First, what types of leadership styles do state supreme court justices themselves think are responsible for effective or ineffective court leadership? Second, are there any differences between male and female state supreme court justices regarding what they think constitutes effective or ineffective court leadership by their chief justices?

Courts — and state courts in particular — provide an excellent forum for examining these questions. Research on gender and leadership has long recognized differences in the leadership styles of men and women across an array of academic disciplines. A traditionally feminine leadership style is generally characterized by interaction.4 It is more democratic and emphasizes collaboration, participation, consensus, and empowerment. A traditionally masculine leadership style, on the other hand, is characterized by autocracy, and the seeking out of opportunities to exert authority over others.5 Past studies have shown that this form of leadership is prevalent in hierarchical organizations that have performance-based cultures, whereas feminine leadership styles are generally perceived to be more effective in flatter organizational structures that emphasize transformation and empowerment.6

Based on our understanding of masculine and feminine leadership styles, it would be sound to assess how justices themselves regard gender differences in leadership on state high courts. State supreme courts are “flat” organizations with every justice exercising equal authority. While state chief justices govern their courts, they are considered leaders among peers rather than leaders of subordinates.7 State supreme court judges also have stated in surveys presented in previous research that a primary task of chief justices is to build consensus in making their rulings.8 The ability to build consensus is commonly referred to as a feminine leadership trait.9 Without adequate consensus, courts can fail to maintain themselves as institutions, which could result in conflict with, and retaliation from, the other branches of government or the public.10 Too much dissensus among justices can sow discord, weaken precedent, confuse the interpretation of the law, and lead to more appeals.11 Since justices already know this, it is interesting to consider whether male and female justices on state high courts seek to adopt feminine leadership styles in their chief justices more generally, and consensus-building skills in particular. To be sure, no uniform method of leadership ensures the interests of a state supreme court or a state court system are protected. However, fostering inter- and intra-court cooperation and consensus appears to be key to effectively promoting and protecting the interests of the courts in state politics. Consensus helps courts achieve their interests.12

This study aims to broaden our understanding of whether state supreme courts are more amenable to a masculine or feminine leadership style by examining what the justices themselves perceive the leadership qualities of their chief justices to be. Next, we attempt to answer whether masculine or feminine leadership styles in state chief justices are desirable by examining what the justices themselves think are the most important duties and responsibilities of their chief justices and what these justices think are the most important skills necessary for a chief justice to possess in order to achieve these goals.

The Study

In order to study state supreme court justices’ perceptions of the types of organization their chief justices lead, whether leadership styles conventionally attributed to women or men may be more successful on state supreme courts, whether state supreme court justices themselves value the leadership qualities that the literature attributes to them, and whether there are differences in preferences depending on the justice’s gender, we constructed a survey questionnaire that was mailed to a total of 587 current and former state supreme court justices in all 50 states. We followed up with telephone calls to each court approximately two weeks after the surveys were received. Justices were assured complete confidentiality and anonymity in their responses and were instructed to not answer any question they thought would breach confidentiality. Those justices who were interviewed via telephone were asked questions from the survey instrument and given the opportunity to answer follow-up, open-ended questions related to the questions in the survey. Phone conversations averaged between 35 minutes to an hour in length. Conversations were transcribed after each interview. Fifty-eight responses were gathered from the survey, a 9.7 percent response rate. Justices from 31 different states responded to the survey. A list of states from which the surveys were returned, as well as other descriptive information about the survey respondents, are presented in Table 1. Forty of the respondents were male, and 18 of the respondents were female. Twenty-three of the justices were either currently serving or previously served as chief justice of their court, for a total of 117 years of service as chief justice among the respondents.

Although the survey asked questions on a variety of subjects, the questions specifically addressed in the analysis are the following:

A: In your opinion, what are the three most important duties/responsibilities of being your court’s chief justice?

B: In your opinion, what are the three most important skills necessary to be an effective leader as a chief justice?

C: In your opinion, what leadership characteristics have you observed that have led to your chief justice being an ineffective leader?

D: In your opinion, are chief justices in a better position than other justices to foster consensus on their court?

Because we know so little about leadership styles and their effectiveness on state supreme courts — let alone whether gendered leadership styles are more or less effective on state supreme courts — this study is mostly exploratory. Although literature on gendered leadership posits that different genders exhibit different leadership styles, we are content to simply explore what the justices themselves have to say about how their courts are led. While it may be possible to statistically model the effects of masculine and feminine leadership styles on state supreme courts, this type of analysis would not tell us whether the justices think — either explicitly or implicitly — that certain leadership qualities are more or less desirable in their chief justices. We believe that the best way to discern what the justices themselves think of leadership on state supreme courts is to ask them.13

Since the duties and responsibilities of state chief justices vary widely from state to state, we have decided to perform our analyses by accounting for whether a chief justice presides over a unified or non-unified court system. Chief justices in unified court systems are responsible for the central administration of their state’s entire court system, whereas chief justices in non-unified systems do not have to handle the central administration of state courts. This distinction is important because unified court systems are hierarchical in form. State supreme courts in non-unified courts are not.14 Chief justices who sit atop a judicial hierarchy in unified court systems should, according to the extant literature, be more amenable to a masculine leadership style. Other important powers — such as the ability to assign opinions, for example — could possibly affect what leadership skills different justices think a chief justice should have.15 We choose to look at differences between unified and non-unified courts specifically because one is hierarchical and one is not, and therefore each could be assumed to align with a different leadership style.16 Thirty-six of our respondents work or have worked on unified courts. Twenty-two of our respondents work or have worked on non-unified courts.

The Duties of the Chief Justice

Figure 1 provides a graphical interpretation of what the justices in the survey volunteered as the most important duties and responsibilities of state supreme court chief justices. The justices in this survey overwhelmingly agreed that the most important duty of their chief justices was to administer the business of their courts. Nearly one third — 31.5 percent — of the answers to the question about the most important duties and responsibilities of the chief justice pertain to effective court administration. This holds true regardless of whether the chief justice is responsible for administering just the state supreme court or the entire state court system. In describing the duty of the chief justice to manage either the supreme court or the state court system, respondents commonly used words such as “set the tone” and “preside.” Several justices said a chief justice should preside over several aspects of the judicial process, including deliberation, oral argument, and judicial conferences; opinion assignment and writing; and interacting with the public and other branches of government. Chief justices were also expected to effectively administer the operations of the lower states courts. Related responsibilities included staffing, budgets and finance, organization, and public relations with other branches of government, the state bar association, and the public. These responses provide strong evidence to support the contention that being an effective state chief justice — just like being an effective Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court — requires effective task management and social leadership.

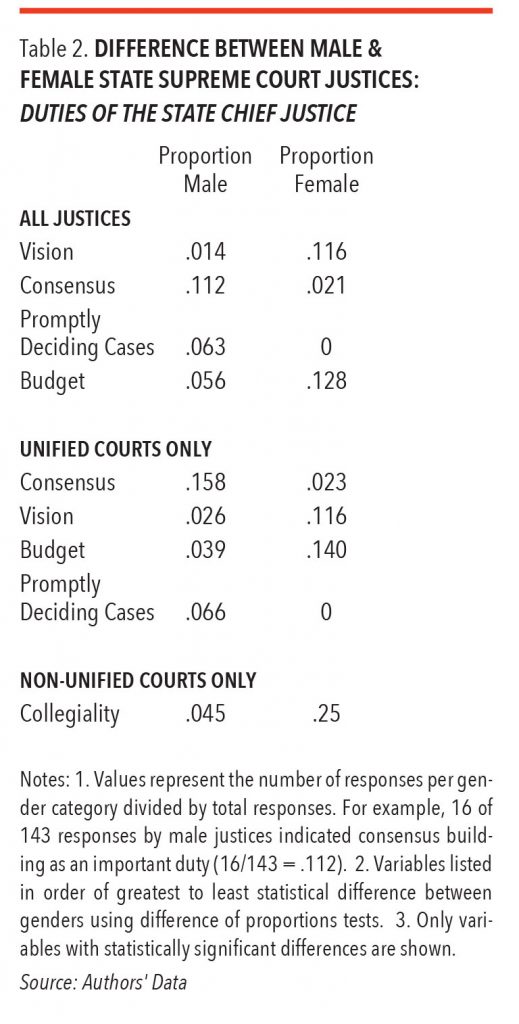

Next, we examined whether male and female respondents had different opinions about which types of duties and responsibilities are most important for a chief justice to accomplish. Table 2 lists the duties specified by the justices in the survey, in order of the greatest differences between male and female respondents. When the justices’ answers are pooled, the duty of “providing the court with a vision” exhibits the greatest difference between male and female justices (z = -2.97, p ≤ .01), with female justices ranking vision as a more important leadership quality than male justices did. The next two important differences concern creating consensus (z = 1.89, p ≤ .05) and efficiently deciding cases (z = 1.77, p ≤ .05), respectively. More male justices than female justices ranked consensus-building as an important responsibility of chief justices. Based on literature about gendered leadership, we might have expected consensus-building to be considered more important by female justices.17 Along with forming a vision for their courts, female justices ranked managing the budgetary process as being a more important duty of chief justices than did their male counterparts (z = -1.64, p ≤ .05).

The duties and responsibilities to which male and female justices assign similar levels of importance tended to be those that were inherent to the job of chief justice and aligned well with the literature on task management and social leadership: public relations, court administration, system administration, and fostering collegiality. An interesting change occurred, however, when we divided the survey responses based on whether or not the respondent operated in a unified court system. Whereas male justices on unified courts viewed collegiality to be more important (though not statistically more so), female justices on non-unified courts viewed the need for chief justices to foster collegiality on their courts to be much more important than did their male counterparts.

A final comparison of the perceived importance of a chief justice’s duties was made by consolidating the several duties and responsibilities mentioned by the justices into two categories. One category represents duties involving the internal operation of the courts, and the second variable represents duties chief justices perform outside the court. Comparing the differences between male and female respondents’ answers on these two variables produced interesting and consistent results. Male justices were much more likely to prioritize the importance of internal court operations than were their female counterparts, regardless of whether they were in a unified or non-unified court system (z = 1.94, p ≤ .05). Female justices, on the other hand, particularly those in unified court systems, consistently emphasized the importance of a chief justice’s duties and responsibilities outside the court (z = -2.03, p ≤ .05). This means that, while male and female justices may similarly prioritize some of the chief justice’s duties, female justices appear to place much more importance on what a chief justice does outside the court — particularly in regard to relationships the chief justice develops with external political or legal actors.

Several conclusions can be reached based on this analysis. First, it is apparent that both male and female justices agreed on the importance of several of the chief justice’s leadership tasks. Among them were court administration, public relations, and fostering collegiality. Administering courts — whether unified or non-unified — was the most cited duty of the chief justice, and there were no substantial differences of opinion between the male and female justices on the importance of this duty. Public relations also fit into this category of responsibilities. Both male and female respondents recognized it as an important component of a chief justice’s job.

Second, male and female justices diverged on the importance of some duties and tasks. For example, male justices thought chief justices should build consensus and “properly” decide cases.18 Female justices thought providing a vision for the court and concentrating on the court’s budget were more important duties. These findings are unique. While deciding cases could be linked to a masculine leadership style, and providing a vision to a feminine leadership style, it is interesting that consensus-building was preferred by male justices. This difference warrants further consideration.

Finally, when the duties and responsibilities were categorized as either internal or external duties and responsibilities, other obvious differences arose. Male justices quite clearly believed that focusing on the internal operations of the court was a more important responsibility, while female justices clearly believed that the most important work for state chief justices was to focus on maintaining relations with external actors.

The Skills of the Chief Justice

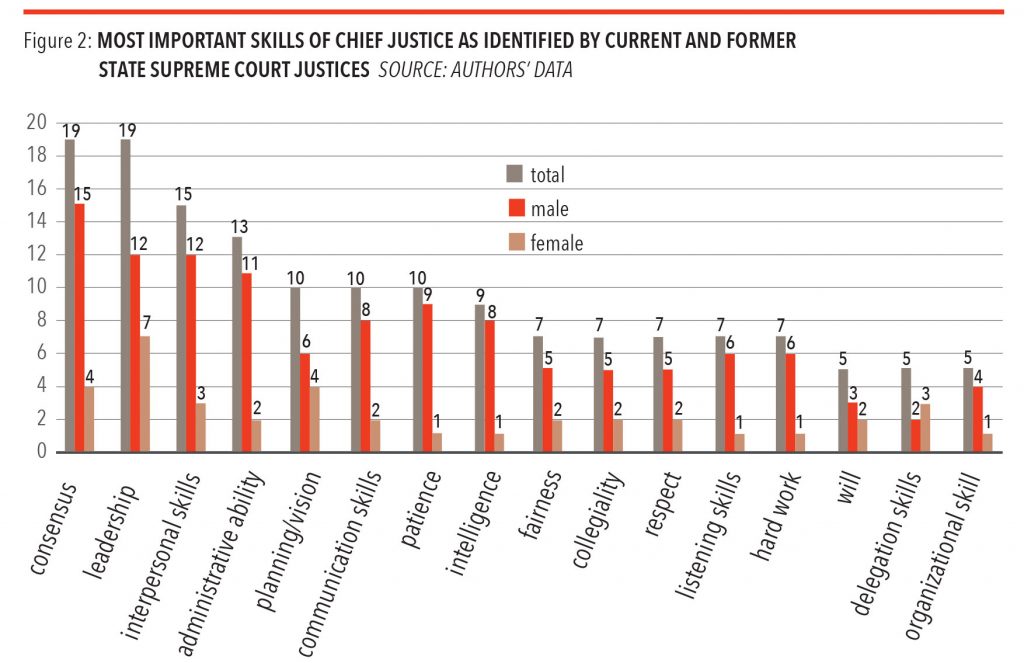

Figure 2 provides a graphical interpretation of what the justices in the survey thought were the most important skills a state chief justice needed in order to be a successful leader. The skills specified by the justices are more numerous than the duties identified as important for the chief justice to perform. Still, there are some notable patterns in the skills male and female justices thought were important for a state chief justice to have.

Despite the diversity of opinions expressed in the survey, leadership capability, consensus-building, interpersonal skills, and administrative ability were perceived as being the most important skills of an effective chief justice, with 11.6 percent of the respondents recognizing “leadership ability” as the most important skill to have. The responses showed many ways to interpret leadership as a requisite skill. Although the term “leadership ability” was mentioned by some justices, other descriptions of leadership ability included: “leading by inspiring others”; “leadership is knowing when to fight, when not to fight, and not being afraid to fight. Upholding the dignity of the office by not backing away from confrontation”; “political skills to deal with the other branches, and with administration”; and “leading by not using a heavy hand.” Interestingly, consensus-building was considered by many to be an important leadership skill and not just a duty the chief justice needs to perform. Consensus-building was not only considered an end for chief justices, but also a means to an end.

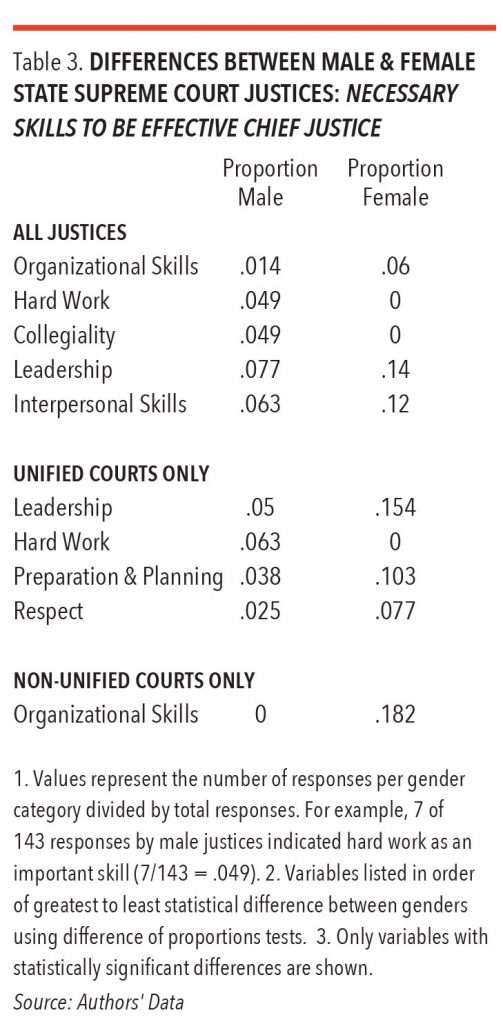

Table 3 lists the skills justices thought a chief justice should have, in order of the greatest differences between male and female respondents. Again, we have pooled all answers and separated them based on whether the respondent served in a unified or non-unified court system. Per the pooled responses in Table 3, organizational skills, the ability to make good decisions, decisiveness, and consistency were the leadership skills with the greatest variation among male and female justices’ responses. Female justices thought leadership was a more important skill than did their male counterparts (z = -1.77, p ≤ .05), while male justices thought collegiality, hard work, patience, and the ability to delegate were more important (z = 1.60, p ≤ .10 for both collegiality and hard work). These skills are an interesting mix and do not fit neatly with expectations of masculine and feminine leadership styles. It could be that justices are suggesting that these skills are necessary for chief justices because they do not have them themselves; however, there is no evidence of this in this survey, and that theory would need to be explored in future research.

It is interesting to note the skills where there was little difference between male and female respondents in the pooled analysis. For example, there was little disagreement about the importance of the ability to plan, the need for intelligence, willpower, communication skills, and the value of humility in order for a chief justice to be a successful leader. But skills such as communication, empathy, humility, ethics, time management, respect, and interpersonal skills were more favored by female justices than male justices. These skills are very commonly associated with a feminine leadership style. Skills such as intelligence, will, and energy are regularly attributed to masculine leadership styles, but were not among the most noted skills by the justices — male or female — in the survey. It could be that the results of this survey would be more robust and significant if the sample size were larger.

Differences between male and female justices changed when examining only justices in unified court systems. In this analysis, leadership traits associated with a masculine leadership style — notably hard work and delegation — rose in importance for male justices. Female leadership traits, too, became important to female justices in unified court systems. Some notable skills important to female justices in unified court systems were ethics, preparation, and respect. It is notable that these skills reflect personal character traits. It could be that although these chief justices are charged with administering these court systems, they are also symbolic representatives of these courts. Therefore, the justices hoped that their chief justices embody the best personal traits that judges and staff themselves aspire to have.

An examination of responses from justices in non-unified courts shows that more female than male justices valued organizational and time-management skills, decisiveness, and humility in a chief justice. No skills stood out among the male justices’ responses as being more or less important when compared to female justices’ responses.

What Makes for an Ineffectual Chief Justice?

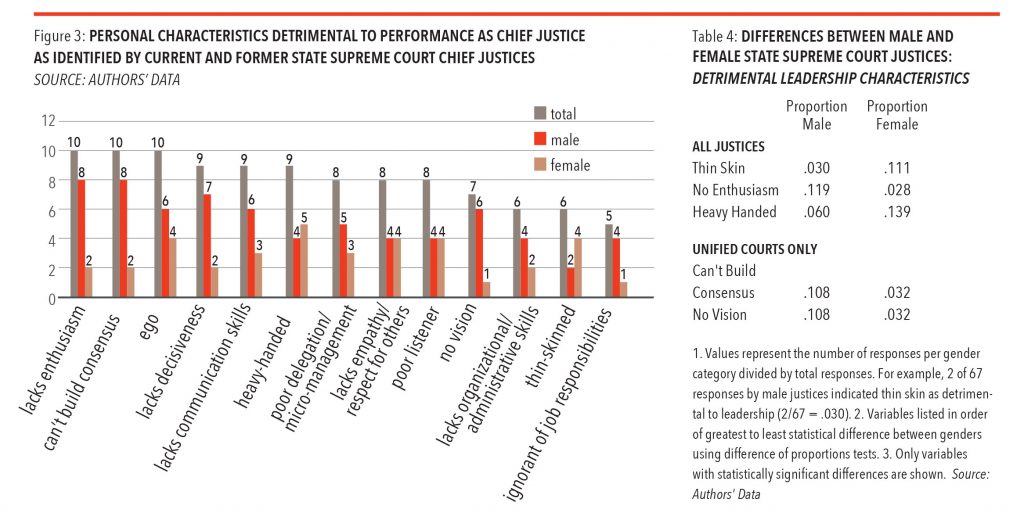

Figure 3 provides a graphical interpretation of the justices’ perceptions of the personal characteristics that make chief justices ineffectual leaders. The characteristics that stood out were typically associated with ineffectual leadership in other organizational contexts: no enthusiasm, poor delegation skills, micromanagement, lack of respect for his or her colleagues, a big ego, heavy-handedness, and a lack of communication skills. A lack of enthusiasm was the most-cited characteristic of an ineffectual chief justice (12 percent of responses).

A comparison of male and female justices’ responses about ineffectual leadership reveals similar views toward these characteristics. T-tests of all types of ineffectual leadership show that there is very little difference between male and female justices’ conclusions that poor delegation skills and micromanagement, ego, lack of organizational or administrative ability, and lack of communication skills result in ineffectual leadership among chief justices.

Table 4 lists the characteristics of ineffectual leadership in order of the greatest differences between male and female respondents. These characteristics are also broken down for unified and non-unified court systems. Having a thin skin, lack of enthusiasm, heavy-handedness, an inability to generate consensus, and a lack of vision were considered ineffectual leadership characteristics. Female justices were more likely than male justices to think that heavy-handedness and a thin skin were detrimental to effective leadership. Heavy-handedness in leadership clearly conflicts with a female leadership style. At first glance, it is interesting that there would be a difference between the views of male and female justices with regard to how much having a thin skin affects a chief justice’s ability to lead. However, many female justices made statements throughout their surveys indicating that chief justices needed to “fight” for their own courts in order to be effective leaders, and that they had to be able to remain strong in the face of harsh opinions and criticisms. It is possible that justices believed that if a chief justice had a “thin skin,” he or she would not be willing or able to successfully fight for the courts they represent in a political arena:

Justice 23: [The chief justice] needs to have competent political skills — almost adversarial.

Justice 34: [The chief justice] must be courageous.

Justice 36: They have to be an effective advocate for the state court system — particularly in budget negotiations.

Justice 55: Courage is necessary. Ego, political favoritism and fear, poor insight and self-promotion, arrogance and an inability to entertain others’ points of view. [These] characteristics lead to failure.

The characteristics and skills that the male justices identified as contributing to ineffective leadership are also interesting. First, consensus-building emerged again as a skill that male justices thought was essential to effective chief justice leadership. The results are telling. These justices also thought it was detrimental to leadership if consensus cannot be achieved. This contrasts with responses about vision. Female justices said vision was a very important leadership trait for chief justices; male justices said it is detrimental to court leadership if chief justices do not have vision.

Again, several characteristics emerge when we look only at unified courts. Male justices still considered the inability to foster consensus and formulate a vision to be detrimental. Female justices still thought heavy-handedness and having a thin skin were detrimental. However, two new factors emerged. First, male and female justices agreed that a lack of enthusiasm was detrimental to chief justice leadership. Second, female justices noted that a lack of respect for others, from others, and for the court system as a whole was detrimental to leadership of the state court system. In the words of one female justice, “[N]ot exhibiting a greater level of self-sacrifice is detrimental [to leadership]. Respect and belief in the institution are key.” In the words of another justice:

“Having served under three chiefs, the commonalities and differences are striking. When faced with important issues (e.g., legislative relations), two would come to the court and say ‘“We have a problem and I’d like to hear your ideas about how to address it.”’ The other would say ‘“We have a problem and I’m going to tell you what to do about it.”’ The dictator took all the credit for everything that went well and blamed others if things didn’t go well. The other two were good listeners, thoughtful and diplomatic, gaining our respect no matter how the situation turned out.”

Differences among male and female justices’ responses about enthusiasm also emerge in non-unified courts. Female justices also saw the lack of communication and listening skills as more detrimental to the success of a chief justice than did their male colleagues. These skills closely align with a female leadership style. Female justices also thought that having a big ego was more detrimental to chief justice leadership than did the male respondents. Often, these leadership weaknesses were thought to be interconnected. For example, when talking about detrimental leadership qualities, one female justice on a non-unified court stated, “[T]he weaker ones tend to be overbearing, overconfident, and poor listeners.”

Conclusion and Discussion

What duties and responsibilities do state supreme court justices think are necessary for a state chief justice to accomplish in order to be an effective leader? What leadership skills should a chief justice exhibit or not exhibit in order to be an effective leader of his or her court? Do male and female justices differ in what they think are the necessary responsibilities and skills of successful state supreme court leaders? This paper provides insight into these questions by examining the answers to an original survey given by state supreme court justices themselves.

Based on the answers to the survey, it is reasonable to conclude that many duties and tasks are thought to be inherent in the position of chief justice. For example, all justices surveyed believed proper court administration to be among a chief justice’s foremost responsibilities. However, differences among male and female respondents emerged with regard to how that administration should take place. Male justices emphasized the need to foster consensus and deal with a court’s internal operations, while female justices emphasized vision and a belief that a chief justice should focus on relationships with external actors who may influence a court’s environment. This last difference is intriguing and warrants further research. Another interesting result is the degree to which male justices emphasized consensus and collegiality when compared to female justices. More research should be devoted to understanding whether or not male chief justices actually foster greater consensus than their female counterparts.

There are similarities between male and female justices regarding their perceptions of the skills necessary to effectively lead as a chief justice — especially when the results were pooled. However, interesting differences emerged when the answers were broken down based on whether the justices operated within unified or non-unified court systems. Here, the results align more closely with expectations in the literature pertaining to how different leadership styles fit within certain types of organizations. Although leadership and organizational abilities were viewed by most justices as essential skills, female justices highlighted emotional skills such as empathy, humility, and respect, while male justices focused on more concrete leadership skills such as hard work and decisiveness. Future research on court leadership needs to pay close attention to differences in leading unified versus non-unified court systems. Dividing courts in this way is not a paramount consideration for this paper; however, the differences in results that occurred because of this consideration should be explored more thoroughly.

Finally, both male and female justices agreed about the attributes of ineffective chief justices. Both male and female justices agreed that a lack of enthusiasm, poor organizational and leadership skills, and a lack of delegation skills and communication skills were detrimental to leadership. Still, there were differences between the genders here, too. Whereas male justices believed that chief justices were ineffective when they could not generate consensus and provide a vision for their courts, female justices believed that heavy-handedness and a lack of respect for others on the court led to ineffective leadership.

These results reveal both similarities and differences of opinion as to what makes chief justices effective leaders of their courts. While a main goal of this paper is to analyze gendered differences in leadership style preferences, we hope that this analysis provides insight for all as to what constitutes effective leadership on state supreme courts.