E-Service Across Borders

by William S. Dodge and Maggie Gardner

Vol. 108 No. 2 (2024) | Judges Under Siege? | Download PDF Version of Article

What are the rules for serving foreign defendants by email?

Lawyers in the United States use email to do many things. Increasingly, they also want district courts to authorize service by email on parties outside the United States under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(f)(3). Service by email may seem particularly attractive for intellectual property owners suing foreign defendants who sell counterfeit products through online platforms such as Amazon. For such defendants, physical addresses can be hard to find, whereas electronic addresses are not.

The problem is that Rule 4(f)(3) allows a court to order service only by means “not prohibited by international agreement.” The United States is one of 84 parties to such an agreement: the Hague Service Convention.1 The convention does not expressly mention email (it was concluded in 1965), and district courts are divided on what this silence means.

Some have held that silence equals permission, which means that email service is not prohibited and is thus permissible under Rule 4(f)(3).2 Some have held that silence equals prohibition since the means of service identified are exclusive, which means that email service is impermissible under Rule 4(f)(3) because it is not among the means identified by the convention.3 Others still have held that email comes within “postal channels” under Article 10(a), which is a means of service that the convention expressly permits so long as the receiving country has not objected.4 Under this interpretation, email service is permitted in countries that have not objected to service by postal channels but is prohibited in those countries that have objected.

District courts have struggled with this question in part because motions for alternative service under Rule 4(f) (3) are often made ex parte, so that the court hears only one side of the argument — the one favoring email service.5 This nonadversarial dynamic can lead to oversights and errors in the case law, on which other judges then rely.6 The question of email service on foreign defendants has also evaded appellate review because many of the cases in which courts have ordered such service result in default judgments that are never appealed.7

This essay provides a guide to the complex interplay of the Hague Service Convention and Rule 4(f). We explain when the convention applies and when it permits email service. We also explain how the convention works with Rule 4(f) and, in particular, when email service is “prohibited by international agreement” for purposes of (f)(3). The most important takeaway is that the convention is mandatory and exclusive when it applies, which means that the convention’s silence is equivalent to a prohibition. Thus, for service by email to be permissible under the convention, it would have to fit within Article 10(a)’s permission for service by postal channels.

The Hague Service Convention

The Hague Service Convention is a multilateral treaty intended “to simplify, standardize, and generally improve the process of serving documents abroad.”8 It also protects the sovereignty of countries that have joined it by limiting the ways in which service can be effected. Unlike the United States, many countries consider service to be a governmental function that private parties may not perform.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that “compliance with the Convention is mandatory in all cases to which it applies,”9 and the convention itself states that it applies “in all cases, in civil or commercial matters, where there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.”10 By its own terms, then, the convention does not apply when the defendant does not reside in a country that is party to the convention, when the defendant can be served in the United States without sending documents abroad, or when the defendant’s address is unknown.

Under the convention, each country designates a “Central Authority” to receive and execute requests for service from other countries.11 Once it has received a request and executed it, the central authority must complete and return a certificate of service.12 A country may refuse to execute a request for service from another party to the convention “only if it deems that compliance would infringe its sovereignty or security.”13

Although the central authority process is the main mechanism for service, the convention expressly permits other methods of service under certain circumstances. First, Article 8 allows the sending state to effectuate service through its diplomatic and consular agents so long as the receiving state has not objected to this method.14

Second, Article 10 identifies three additional methods that are similarly available only if the receiving state has not objected. Article 10(a) permits service through “postal channels,”15 which (as described further below) may include email. Article 10(b) allows judicial officers or other competent persons in the sending state to serve process directly through judicial officers or other competent persons in the receiving state — that is, without going through the receiving state’s central authority. And Article 10(c) allows parties to litigation in the sending state to serve process directly through judicial officers or other competent persons in the receiving state. A receiving state may object to some or all of the methods laid out in Article 10 or may impose conditions on their use. The Hague Conference website maintains a list of contracting states and the objections they have made, making this information easy to find.16

Third, Article 11 allows countries that have joined the convention to agree on additional methods of service through separate bilateral or multilateral agreements.

And fourth, Article 19 allows a receiving state to consent unilaterally to additional methods of service from abroad through provisions in its own domestic law.

Rule 4(f)(3) and the Exclusive Character of the Convention

Of course, service must also be authorized as a matter of U.S. law.17 Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(f) sets forth permissible methods of service for an individual “at a place not within any judicial district of the United States.” Rule 4(h)(2) incorporates Rule 4(f) (with one minor exception) for service on a business “at a place not within any judicial district of the United States.”18

Rule 4(f) is designed to work in tandem with the Hague Service Convention. It identifies three options for international service:

1) by any internationally agreed means of service that is reasonably calculated to give notice, such as those authorized by the Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents;

2) if there is no internationally agreed means, or if an international agreement allows but does not specify other means, by a method that is reasonably calculated to give notice:

A) as prescribed by the foreign country’s law for service in that country in an action in its courts of general jurisdiction;

B) as the foreign authority directs in response to a letter rogatory or letter of request; or

C) unless prohibited by the foreign country’s law, by:

i) delivering a copy of the summons and of the complaint to the individual personally; or

ii) using any form of mail that the clerk addresses and sends to the individual and that requires a signed receipt; or

3) by other means not prohibited by international agreement, as the court orders.19

In an oft-cited case in which the convention was not applicable, the Ninth Circuit held that the three options in Rule 4(f) are nonhierarchical, meaning that the plaintiff need not attempt service under (f)(1) or (f)(2) before seeking court authorization for alternative forms of service under (f)(3).20 Accepting this reading of the rule, (f)(3) nonetheless sets its own limits on its applicability.

Rule 4(f)(3) limits alternative forms of service to “other means not prohibited by international agreement.” The Hague Service Convention prohibits any form of service it does not expressly permit because it is mandatory and exclusive when it applies. That means Rule 4(f)(3) rules out any form of service not expressly permitted under the convention. Understanding Rule 4(f)(3) thus turns on understanding the exclusive character of the convention.

That exclusive character is already established. The Supreme Court has explained that when the convention applies, it “provide[s] the exclusive means of valid service.”21 Similarly, the Department of Justice has stated that “[i]f the Convention applies, parties cannot agree or stipulate to a method of service that the Convention neither authorizes nor permits.”22

But the exclusive character of the convention is also clear from its “text and structure.”23 In particular, all of the means of service permitted by the convention require the receiving state’s consent. By joining the convention, states agree to accept requests for service through a central authority. Articles 8 and 10 authorize certain additional means of service, including service by “postal channels,” but they allow countries to opt out of those means of service by objecting to them. In contrast, states have no option for objecting to forms of service not listed in the convention. Articles 11 and 19 allow contracting states to expressly permit additional means of service through separate agreements or their own domestic laws. If the convention were not exclusive and other means of service were permissible, these articles would be largely superfluous.24 In short, if silence is read as permission, any method not mentioned in the convention — service through TikTok, for example — would be allowed, with no requirement of affirmative consent and no way for a state to object.

“[T]he Convention’s drafting history, the views of the Executive, and the views of other signatories”25 also support reading the convention to prohibit any means of service to which the receiving state has not affirmatively consented. The authoritative account of the convention’s drafting history explains that “[t]he drafting group considered at length” the question of whether “the means of service provided by the Convention constituted the exclusive means of service of judicial documents in the territories of the contracting states.”26 Ultimately, “certain revisions were made to make it clear that the Convention machinery must be employed in all cases where service of process abroad is sought,” with the result that “the Convention machinery is obligatory.”27

The positions of other contracting states confirm this understanding.28 In 2003, 2009, and 2024, special commissions with broad representation from countries that have joined the convention adopted conclusions and recommendations confirming the convention’s “exclusive character.”29 Citing the conclusions and recommendations of the 2003 and 2009 special commissions, the most recent edition of the Practical Handbook on the Operation of the Service Convention issued by the Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law states that “the Convention’s exclusive character is now undisputed. Thus, if under the law of the forum a judicial or extrajudicial document is to be transmitted abroad for service, the Convention applies and it provides the relevant catalogue of possible means of transmission for service abroad.”30

In short, the convention provides a closed universe of permissible means of service, effectively prohibiting other means that are not specified. Because Rule 4(f)(3) is limited to alternative means of service “not prohibited by international agreement,” it cannot be used to expand the menu of options available under the convention.

Serving Foreign Defendants by Email

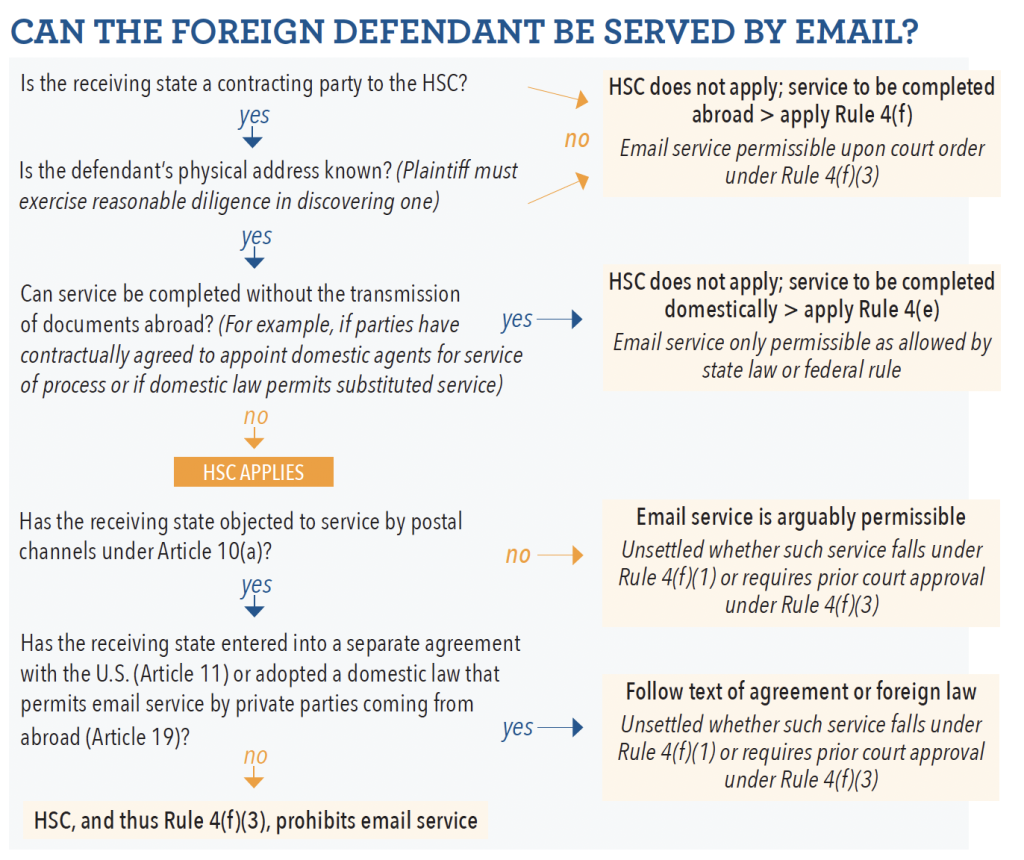

So, when can a federal court authorize service by email under Rule 4(f)(3)? They can definitely do so if they conclude that the convention does not apply. Even if the convention does apply, they may still be able to do so if the receiving state has not objected to service by “postal channels” under Article 10(a). But if the convention applies and the receiving state has objected to service by postal channels under Article 10(a), then service by email is almost surely impermissible.

When the Convention Does Not Apply

There are three common scenarios in which the convention does not apply. First and most obviously, it does not apply if the country in which service is sought has not joined the convention.

Second, Article 1 of the convention states that “[t]his Convention shall not apply where the address of the person to be served with the document is not known.” Given that Rule 4(f)(3) motions are typically made ex parte, it falls to the district court to ensure that the address of the person to be served is in fact unknown. Federal courts have required plaintiffs to show “reasonable diligence” in their efforts to identify or confirm physical addresses of defendants.31 They have also clarified that the convention still applies even if the defendant has avoided service at its known address: In the Third Circuit’s words, there is “a difference between situations where the defendant’s address is not known and the defendant’s whereabouts are not known.”32 In the latter situation, the convention still applies.

Third, Article 1 also limits the convention to instances in which “there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.” That means if service can be completed within the United States, the convention does not apply.33 The Supreme Court has held, for example, that the convention does not apply when the foreign defendant can be served within the United States through substituted service, as provided by state law.34

But note that when service is completed within the United States, service is governed not by Rule 4(f) but rather by Rule 4(e).35 Rule 4(e)(1) permits service in accordance with state law, while Rule 4(e)(2)(C) permits service on “an agent authorized by appointment or by law to receive service of process.” The service within the United States, including service by email, must fall within one of these categories. Rule 4(f)(3) cannot be used to devise ad hoc forms of service within the United States because Rule 4(f) by its own terms does not apply unless service is to be completed abroad.

Under Rule 4(e)(2)(c), the parties might agree in advance to appoint domestic agents for service of process and to accept email service on those agents. Parties have limited ability to contract around the convention, however. While parties can agree to accept service within the United States — as well as agree to the format of such service — they cannot agree to means of service that entail the transmission of documents outside the United States if those means conflict with the convention.36 Thus, a contractual agreement to accept service by email in a country that has joined the convention, even if acceptable as a matter of U.S. domestic law, does not relieve the plaintiff and the U.S. court from the obligation to comply with convention procedures.

When the Convention Applies but the Contracting State Has Not Objected to Service by “Postal Channels” under Article 10(a)

As noted above, when the convention applies, Rule 4(f)(3) cannot be used to order service by means not permitted by the convention. However, the convention does permit service through “postal channels” under Article 10(a) so long as the receiving state has not objected to it. Some courts have interpreted “postal channels” as encompassing electronic mail.37 Under this reading, contracting states that have not objected to the use of postal channels under Article 10(a) accept service by email.

That interpretation has recently been bolstered by the conclusions and recommendations of a special commission, convened in July 2024 and comprising delegates from 57 contracting states, including the United States. That commission “noted that Article 10(a) includes transmission and service by e-mail.”38 This understanding aligns with the special commissions’ prior interpretations of “postal channels” to cover other forms of correspondence outside of government-controlled mail systems, including telegrams, telexes, FedEx, and UPS.39

The U.S. government, for its part, agrees that email is a “postal channel” under Article 10(a),40 and the Supreme Court “gives ‘great weight’ to ‘the Executive Branch’s interpretation of a treaty.’”41 In light of this emerging consensus, email service on defendants in contracting states that have not objected to such service under Article 10(a) may be considered permissible.

There must also be authorization to serve by email under U.S. domestic law,42 which is found in Rule 4(f). An unsettled question, however, is whether service by email under Article 10(a) is an “internationally agreed means of service” under Rule 4(f)(1) or whether prior court approval is needed under Rule 4(f)(3).43 One view is that Rule 4(f)(1) only covers service through central authorities because that is the sole channel of service that the convention affirmatively authorizes. If so, other forms of service permitted by the convention must still be approved by the U.S. court via Rule 4(f)(3). Another view is that Rule 4(f)(1) covers the alternative channels of service under Articles 8 and 10 because contracting parties have “agreed” to those means in the convention so long as the receiving state has not objected to them. A similar argument could be made for additional methods of service agreed to by some subset of countries as envisioned by Article 11. Such bilateral arrangements are by definition “internationally agreed means.”

Article 19, which allows a receiving state to authorize additional methods of service in its domestic law, presents a more difficult question. If the contracting state’s domestic law permits service by email from abroad, one might argue that the parties to the Hague Convention “agreed” to it by including Article 19 in the convention. On the other hand, the methods covered by Article 19 are authorized unilaterally by the receiving state and so are not specifically agreed between two or more countries. Indeed, they may encompass means of service unfamiliar to U.S. law. Treating Article 19 methods of service as not “internationally agreed,” and thus requiring U.S. court approval under Rule 4(f)(3), would have the benefit of enabling the district court to make its own determination about whether such service is in fact permitted under foreign law and is constitutionally sufficient under U.S. law.

To the extent that parties rely on Rule 4(f)(1) when invoking service by email under Article 10(a), Rule 4(f)(1)’s caveat that the “internationally agreed means of service [be] reasonably calculated to give notice” provides an explicit hook for courts to supervise email service to ensure that it is likely to reach the defendant. Regardless, a cautious plaintiff might wish to seek preapproval under Rule 4(f)(3) for email service pursuant to Article 10(a).

When the Convention Applies and the Contracting State Has Objected to Article 10(a)

If a contracting state has affirmatively objected to Article 10(a), then there is no other textual hook for service by email in the convention, which means that the convention’s mandatory and exclusive character effectively prohibits service by email. And if the convention prohibits service by email, then Rule 4(f)(3) cannot be used to authorize it on an ad hoc basis.

This scenario is not uncommon. Eighteen contracting states have filed declarations objecting to service under Article 10(a), including China, India, Mexico, Germany, and Singapore.44 Even in this scenario, however, there are two ways that service by email may still be used — though most likely with the assistance of local government authorities.

First, Article 5(b) allows parties to request that the central authority arrange service “by a particular method requested by the applicant, unless such a method is incompatible with the law of the State addressed.”45 That can include a request to serve by email, particularly if initial attempts to serve the defendant at its physical address have failed.46 But note that such email service must be made by the receiving state’s central authority. Article 5(b) does not permit email service directly by a party to the litigation.

Second, Article 19 recognizes that contracting states may permit additional methods of transmission for “documents coming from abroad, for service within [their] territory,” which could include service by email. The party seeking service has the burden of identifying the content of foreign law, but under Rule 44.1, courts “may consider any relevant material or source, including testimony, whether or not submitted by a party or admissible under the Federal Rules of Evidence.” This can include appointing an amicus to provide an impartial assessment of the foreign law.47

Even when a contracting state’s internal law permits service from abroad by electronic means, however, it may require such service to be made by a court or other governmental official. That is, the fact that a state accepts service by email does not necessarily mean it accepts email service made by a private party. In that situation, the proper route is to request that the contracting state’s central authority serve by email under Article 5(b).

Cases of Exigency or Delay

Some U.S. courts have suggested that Article 15 and Rule 4(f)(3) allow courts to order additional means of service in cases of urgency or when a central authority has taken more than six months to complete service.48 Article 15 addresses the entry of default judgments. It allows contracting states to declare, as the United States has done,49 that a judge “may give judgment even if no certificate of service or delivery has been received” as long as service has been attempted through convention channels and at least six months have elapsed. Article 15 also protects the ability of a judge to “order, in case of urgency, any provisional or protective measures.”

The difficulty is that Article 15 does not itself authorize additional means of service — it simply allows judges to act without completed service.50 It is a separate question whether domestic U.S. law requires completed service before provisional measures or default judgments can be entered. If so, service must still be completed pursuant to Rule 4, Rule 4(f)(3) is still limited to means not “prohibited by international agreement,” and the convention still prohibits any means of service to which the receiving state has not consented. In short, the flexibility that Article 15 provides only helps in instances when U.S. domestic law does not require completed service.

The problem is not acute for preliminary measures because many such measures can be entered without completion of formal service. More challenging is the question of default judgments. But note that this situation arises only when a number of factors are present: the defendant is at a known address in a country that has objected to all other alternative means of service under the convention and the relevant central authority has been unable to complete service within six months.

Conclusion

The intersection of Rule 4(f) and the Hague Service Convention is complicated. Because the convention provides an exclusive set of options for serving defendants abroad, any means not covered is prohibited. That in turn limits the ability of federal courts under Rule 4(f)(3) to authorize ad hoc forms of service in countries that belong to the convention. It is important for courts not to ignore the convention’s exclusive character out of a sense of expediency or practicality. Approving service by email when it is prohibited by the convention not only undermines U.S. treaty obligations but also offends the sovereignty of other nations that treat service within their territory as a sovereign function.

When service by email is sought for a defendant residing in a country that has joined the convention, there are three main options: First, email service can be authorized if the defendant’s physical address is not known (and the plaintiff has made reasonably diligent efforts to ascertain it). Second, email service can be authorized if such service will be completed within the United States pursuant to Rule 4(e). Third, email service may be authorized if the receiving state has not objected to the use of postal channels under Article 10(a). Indeed, the emerging consensus that Article 10(a) includes service by email is an important practical step toward fitting email service within the structure of the Hague Service Convention.

William S. Dodge is the Lobingier Professor of Comparative Law and Jurisprudence at the George Washington University Law School. He is a founding editor of the Transnational Litigation Blog (TLBlog.org), co-author of Transnational Litigation in a Nutshell (2d ed. 2021), and a reporter for the Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law.

Maggie Gardner is a professor of law at Cornell Law School and a founding editor of the Transnational Litigation Blog (TLBlog.org).

- Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters, Nov. 15, 1965, 20 U.S.T. 361 (1969) [hereinafter Hague Service Convention]. For the parties and their various declarations and reservations, see Status Table, Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=17.

- See, e.g., Peanuts Worldwide LLC v. P’ships and Unincorporated Ass’ns Identified on Sched. “A”, No. 23 C 2965, 2024 WL 3161661, at *9–10 (N.D. Ill. June 25, 2024); Teetex LLC v. Zeetex, LLC, No. 20-cv-07092-JSW, 2022 WL 4096881, at *2 (N.D. Cal. Jul. 5, 2022).

- See, e.g., Duong v. DDG BIM Services LLC, 700 F. Supp. 3d 1088, 1093–95 (M.D. Fla., 2023); Smart Study Co. Ltd. v. Acuteye-US, 620 F. Supp. 3d 1382, 1393–99 (S.D.N.Y. 2022).

- See, e.g., Uipath Inc. v. Shanghai Yunkuo Info. Tech. Co., No. 23 CIV. 7835 (LGS), 2023 WL 8600547, at *1–2 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 12, 2023).

- See Smart Study, 620 F. Supp. 3d at 1401 (“[M] any requests by plaintiffs to serve a defendant in China by email are unopposed … [so] courts are unlikely to be alerted to authority that casts doubt on the propriety of their request for email service.”).

- See generally Maggie Gardner, Dangerous Citations, 95 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1619 (2020) (discussing the risks of error when district courts rely on prior district court decisions).

- The Third Circuit recently became the first to address these questions but did so in an unpublished decision. See SEC v. Lahr, No. 22-2497, 2024 WL 3518309 (3d Cir. July 24, 2024).

- Water Splash Inc. v. Menon, 581 U.S. 271, 273 (2017).

- Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v. Schlunk, 486 U.S. 694, 705 (1988).

- Hague Service Convention art. 1.

- Id. art. 2.

- Id. art. 6.

- Id. art. 13. This is a narrow exception: As Article 13 further explains, a central authority “may not refuse to comply solely on the ground that, under its internal law, it claims exclusive jurisdiction over the subject-matter of the action or that its internal law would not permit the action upon which the application is based.”

- A state may not object to the use of this method with respect to service on nationals of the sending states. Id. art. 8.

- Although the text of Article 10(a) uses the word “send” rather than “serve,” the Supreme Court has held that “Article 10(a) encompasses service.” Water Splash Inc., 581 U.S. at 284.

- See Status Table, supra note 1.

- Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 284 (citing Brockmeyer v. May, 383 F.3d 798, 803–04 (9th Cir. 2004)).

- Personal service under Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(f)(2)(C)(i) is excluded by Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(h)(2).

- Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(f).

- Rio Props. Inc. v. Rio Int’l Interlink, 284 F.3d 1007, 1015 (9th Cir. 2002) (“By all indications, court-

directed service under Rule 4(f)(3) is as favored as service available under Rule 4(f)(1) or Rule

4(f)(2).”). - Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft, 486 U.S. at 705.

- U.S. Dep’t of Just., OIJA Guidance on Service Abroad in U.S. Litigation 4–5 (2018), https://www.justice.gov/civil/page/file/1064896/download.

- Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 279 (relying on the “text and structure” of the convention to interpret Article 10(a)).

- See id. at 278 (rejecting an interpretation of the convention as “structurally implausible” because it rendered Article 10(a) “superfluous”).

- Id. at 280 (noting that these sources are “especially helpful in ascertaining [the] meaning” of the convention).

- Bruno Ristau, International Judicial Assistance § 4–1–5, 160 (2000 rev. ed.); see also Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 281 (citing International Judicial Assistance).

- Ristau, supra note 26.

- See Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 283 (“[T]his Court has given ‘considerable weight’ to the views of other parties to a treaty.”) (quoting Abbott v. Abbott, 560 U.S. 1, 16 (2010)).

- Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, Conclusions and Recommendations Adopted by the Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the Apostille, Evidence and Service Conventions ¶ 73 (2003), https://assets.hcch.net/docs/0edbc4f7-675b-4b7b-8e1c-2c1998655a3e.pdf (representatives from 57 countries including the United States); Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, Conclusions and Recommendations Adopted by the Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the Hague Apostille, Service, Taking of Evidence and Access to Justice Conventions ¶ 12 (2009), https://assets.hcch.net/docs/5bf65314-4f55-42b5-9b0c-770f2bfccd37.pdf (representatives from 64 countries including the United States); Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, Conclusions and Recommendations Adopted by the Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the Hague Service, Taking of Evidence and Access to Justice Conventions ¶ 66 (2024), https://assets.hcch.net/docs/6aef5b3a-a02c-408f-8277-8c995d56f255.pdf (representatives from 57 countries including the United States) [hereinafter 2024 C&R]; see also Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 283 & n.8 (relying on the conclusions of special commissions as reflecting the views of the parties to the convention).

- Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, Practical Handbook on the Operation of the Service Convention ¶ 50 (2016) (emphasis added; other emphases removed) [hereinafter Practical Handbook]. The Practical Handbook goes on to observe that “[t] he exclusive character of the Convention was never really disputed. It has been confirmed by case law and by legal scholars, as well as by the Special Commission.” Practical Handbook ¶ 51 (emphases removed); see also Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 280 (citing Practical Handbook).

- See, e.g., Smart Study Co. Ltd., 620 F. Supp. 3d at 1390-91; NBA Props. Inc. v. P’ships and Unincorporated Ass’ns Identified in Sched. “A”, 549 F. Supp. 3d 790, 795–96 (N.D. Ill. 2021), aff’d sub nom. NBA Props. Inc. v. HANWJH, 46 F.4th 614 (7th Cir. 2022); Luxottica Group S.p.A. v. P’Ships and Unincorporated Ass’ns Identified on Sched. “A”, 391 F. Supp. 3d 816, 822–24 (N.D. Ill. 2019).

- Lahr, No. 22-2497, 2024 WL 3518309, at *4 (3d Cir. July 24, 2024).

- See Practical Handbook, supra note 30, at 47.

- Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft, 486 U.S. at 70; see also William S. Dodge, Substituted Service and the Hague Service Convention, 63 William & Mary L. Rev. 1485 (2022) (discussing state laws on substituted service).

- See also Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(h)(1).

- See John F. Coyle, Robin J. Effron & Maggie Gardner, Contracting Around the Hague Service Convention, 53 U.C. Davis L. Rev. Online 53, 56 (2019); see also 2024 C&R, supra note 29, ¶ 111 (questioning the legality and advisability of private contractual arrangements for alternative means of service).

- See supra note 4.

- 2024 C&R, supra note 29, ¶ 105. The special commission noted that contracting states can file a qualified declaration under Article 10(a) to specify what forms of postal channels they accept and under what conditions. See id. at ¶ 107. For an exegesis of this conclusion and recommendation, see Ted Folkman, A Big Step Forward for Service by Email under the Hague Service Convention, Transnat’l Litig. Blog (July 18, 2024), https://tlblog.org/a-big-step-forward-for-service-by-email-under-the-hague-service-convention/.

- Folkman, supra note 38.

- See Questionnaire relating to the Convention of 15 November 1965 on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters (Service Convention), Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law ¶ 23.3, https://assets.hcch.net/docs/e40165e3-4301-41fe-8d70-3d34a3e251ed.pdf (listing email as one of the “categories [that the United States] recognize[s] as a ‘postal channel’ under Article 10(a)”).

- Water Splash Inc., 581 U.S. at 281 (citing Abbott, 560 U.S. at 15).

- See 2024 C&R, supra note 29, ¶ 105; see also Water Splash, 581 U.S. at 284 (applying a similar principle for service by mail).

- As currently written, Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(f)(2) is inapplicable to the convention because the convention is not “an international agreement [that] allows but does not specify other means” of service.

- For information on declarations, see Status Table, supra note 1.

- Hague Service Convention, art. 5(b).

- See Lahr, No. 22-2497, 2024 WL 3518309, at *5 n.16 (3d Cir. July 24, 2024) (noting possibility of requesting email service under Article 5).

- See Smart Study Co. Ltd., 620 F. Supp. 3d at 1388 (noting appointment of expert on Chinese law as amicus).

- See, e.g., Footprint Int’l LLC v. Footprint Asia Ltd., No. CV-24-00093-PHX-DGC, 2024 WL 1556347, at *3 (D. Ariz. Apr. 9, 2024) (urgency); Parsons v. Shenzen Fest Tech. Co. Ltd., Case No. 18 CV 08506, 2021 WL 767620, *3 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 26, 2021) (two-year delay).

- See Declaration/Reservation/Notification, Hague Conf. on Priv. Int’l Law, https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/notifications/?csid=428&disp=resdn (United States).

- The advisory committee notes to Rule 4, to the extent they suggest otherwise, misread the clear text of Article 15. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 4, advisory committee’s note to 1993 amendment.