by Kannon K. Shanmugam, Sarah Boyce and Erwin Chemerinsky

Vol. 106 No. 3 (2023) | Forging New Trails | Download PDF Version of Article

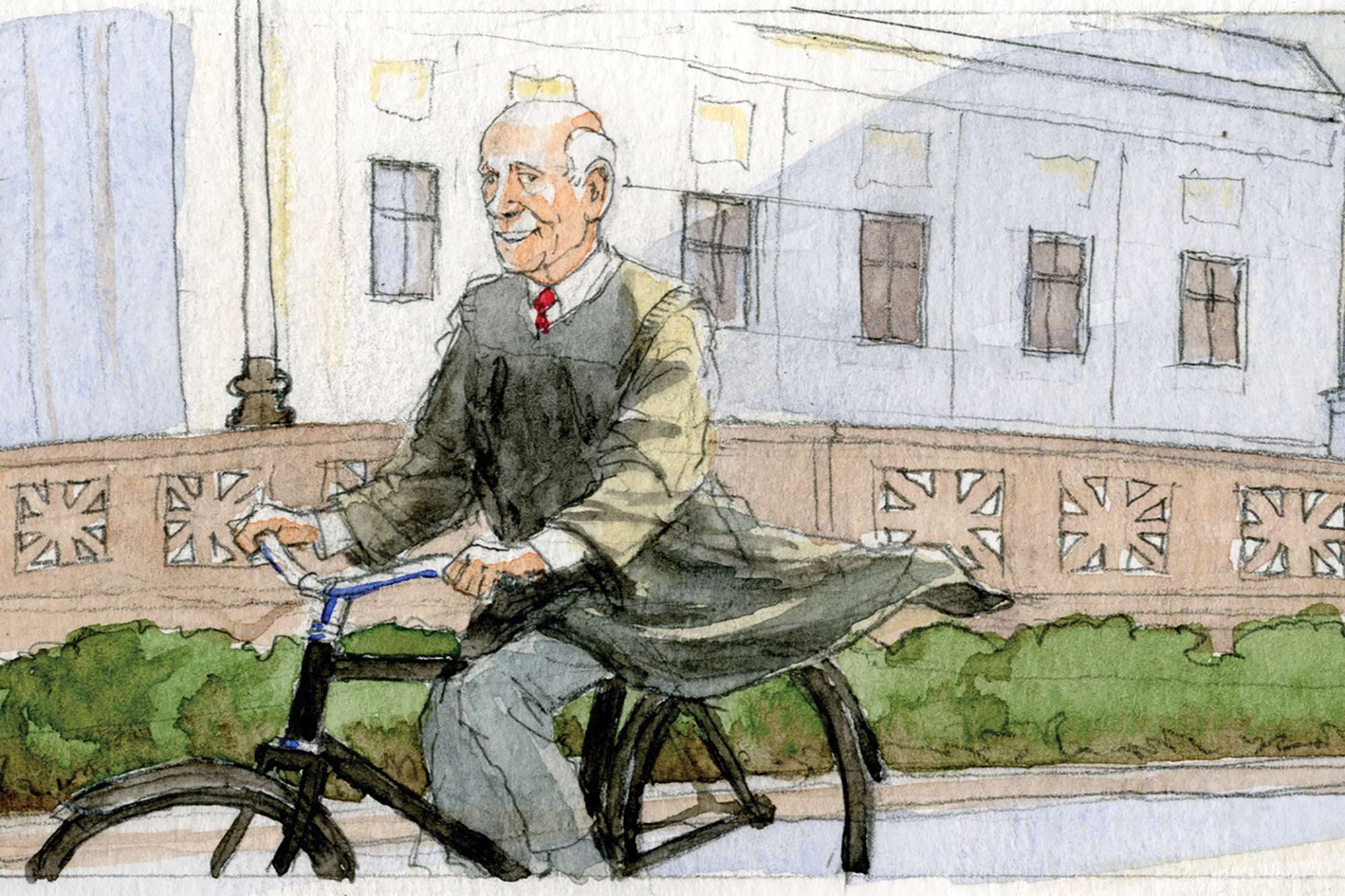

Justice Stephen Breyer’s retirement from the Supreme Court closes the book on a nearly 30-year term filled with erudite opinions. But it also marks the end of a unique presence in oral arguments. Court watchers, advocates, and students will not soon forget the famous Justice Breyer hypotheticals.

These what-if scenarios varied in silliness and complexity. On one occasion, he wondered aloud which state might be able to claim rights to the famous San Francisco fog if it were bottled up and flown to Colorado.1 On another, Justice Breyer queried whether you could patent a process whereby aspirin changed the color of your little finger depending on the suitability of the dosage.2

But the hypothetical games were not just opportunities to inject humor into the Court’s austere business. They were the Justice’s colorful attempts at distilling exceedingly complex legal questions into their core components.

In Carachuri-Rosendo v. Holder,3 Justice Breyer invented the concept of “pussycat burglars” to demonstrate the arbitrariness of a bright-line rule that divides violent offenders from the nonviolent offenders under the federal Armed Career Criminal Act. A pussycat burglar, according to his imagination, is a variety of cat burglar who has “never harmed a soul.”4

In oral arguments, Breyer asked: “It is absolutely established that this person in breaking into that house at night only wanted to steal a pop gun, and he is the least likely to cause harm in the world. Question: He is convicted of burglary. Is that a crime of violence? … The answer is ‘of course,’ because we are not looking to whether he is the pussycat burglar or the cat burglar. We are to look to the statute of conviction and see what it is that that behavior forbids — the statute forbids.”5

In breaking down the strict categorical rule to its basic components, Justice Breyer revealed the value of an ad absurdum argument. As the Justice knew, sometimes absurdity can be used as a scalpel to cut out poor argumentation.

Three people who had the chance to work closely with Justice Breyer over the course of his long career share their stories of his famous hypotheticals here. KANNON K. SHANMUGAM, a partner at Paul, Weiss and a leading advocate before the Court, shares his experience on the receiving end of Justice Breyer’s longest question. ERWIN CHEMERINSKY, noted constitutional law scholar and dean of the University of California–Berkeley, School of Law, explains how Justice Breyer’s questions were designed to give attorneys a chance to address core legal questions. SARAH BOYCE, a former Breyer clerk and current deputy solicitor general of North Carolina, details how the Justice’s approach to questioning reflected his role on the Court and relationship with his colleagues. May their tales remind us of a judge whose imagination and intelligence will long illuminate the Court.

I was on the receiving end of what was perhaps Justice Breyer’s longest question — in a judicial career that was famous for them. The question came in a case called Republic of Sudan v. Harrison; I was representing the victims of the USS Cole bombing, who were seeking to recover from Sudan for supporting the terrorists responsible for the attack:

JUSTICE BREYER: . . . All right. But I — I have a question. And Sumption’s a good judge, and so I read that and paid attention to that, but I agree with you, it’s textual.

That’s your argument. And I find it ambiguous, so we’ll assume it’s ambiguous. I look to purpose, Justice Sotomayor did, and I — I cut that a little against you because you had mentioned — left one word out of your beginning. You said you want a $300 million judgment. You left out the word default.

It was a default judgment. And, of course, that’s the concern, that’s the purpose concern, that they have one ambassador, an assistant, and four people working in the mail room who are all American citizens and never even been to the country. And they don’t know what to do. And you only have 60 days to answer. Okay? And so who knows what’s going to happen to that piece of paper in many embassies. More than 60 days before they even get it over in their country. All right? But purpose, I’ll give you something on that, because that’s not my question.

Then I — I thought: Well, can’t get too far on purpose. Not sure about consequences. What about history and tradition? And there I asked my law clerk to go look up what other countries do, and this is what I found. I found — of course, we have five here, Austria, Libya, Saudi Arabia, the UAR, and the Sudan, and they all say we do it the State Department’s way. Then Canada, the same. Belgium, the same. Twenty-two countries have signed a — a — a — a convention which says, in the absence of an existing agreement, service on a foreign country must be to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Okay? That’s — so we got 22 more.

And then I tried to find one the other way. Couldn’t find one. Well, Sumption. And what Sumption was about is what he said. It was about a former ambassador of service in his residence. And they say foreign states are different. And then there’s some language that helps you. And then I looked to what we did here, and what we did here is that Congress wanted to do it your way, and State wrote them a letter, and nobody says that that Vienna Convention on inviolability is clearly yours or clearly theirs. What they say is there’s an issue about it.

And because — and there is an issue. And because there is an issue, they said to Congress, the state, don’t do it, this isn’t the way we do it. And after the state wrote them that letter, they changed the law. They dropped the language that said you can serve an embassy. Okay?

So, so far, I have U.S. history. I have at least 22 — 27 countries. I could find nothing the other way, except arguable dictum in a case that involves something else.

Now I put that long question to you because I want to give you a chance to say no, I’m wrong, there are 32 countries who do it differently, or whatever you want to say.6

According to Tony Mauro, who was covering the argument for Law.com, the question took up more than three minutes of my 30-minute argument (and 69 lines in the ensuing transcript).7

That question got a lot of attention, but what didn’t get as much notice was that I gave an even longer answer in response — 87 lines,8 by far the longest uninterrupted period of speaking in my career as a Supreme Court advocate. I think the rest of the Court refrained from interrupting because they took pity on me for having to answer such a long question!

Regardless of the duration of the questions, it was always a privilege to appear before Justice Breyer — he was as courtly and inquisitive on the bench as he was off it. I know I speak for the rest of the Supreme Court Bar when I say that we will miss him very much.

— KANNON K. SHANMUGAM chairs the Supreme Court and Appellate Practice Group and is managing partner for Paul, Weiss, in Washington, D.C.

Like all lawyers who appeared before Justice Stephen Breyer, I sometimes was asked long questions that could be hard to follow. I watched my minutes ticking down, hoping he would finish the question.

But I always tremendously appreciated Justice Breyer’s questions because they gave me a sense of what most concerned him about my position. It was exactly what I wanted: a chance to address what he thought most important.

For example, in Van Orden v. Perry, in 2005, the issue was whether it violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment for Texas to have a large Ten Commandments monument directly at the corner between the Texas State Capitol and the Texas Supreme Court. Justice Breyer, in a long question, said that the only way he knew how to draw the line between the permissible and the impermissible was in terms of what was likely to be divisive in society.

After the oral argument, I felt good about my answer. I explained that the Ten Commandments monument was inherently divisive; that is why there were protestors outside the Court and why I had received death threats in the prior week. But after I read Breyer’s opinion, I realized he had given me the chance to address his primary concern and I had not done so.

I lost 5-4, with Breyer concurring in the judgment, and with Justices Stevens, O’Connor, Souter, and Ginsburg dissenting. Breyer’s opinion stressed that divisiveness was crucial in interpreting the Establishment Clause and taking down the monument would be very divisive.

In hindsight, I wish I had answered his question differently and taken advantage of Breyer’s opportunity to address his concern. I should have explained why divisiveness does not work as a principle for the Establishment Clause because any enforcement of it is inherently divisive in preventing some from doing what they want to advance religion. I am sure my answer would not have changed the outcome of the case, but I wish I had better answered his question.

Justice Breyer always was unfailingly polite to lawyers and to everyone. At a time when too many justices resort to sarcasm and invective, Justice Breyer never did. And that, most of all, will be missed.

— ERWIN CHEMERINSKY is dean of the University of California–Berkeley School of Law.

JUSTICE BREYER: Suppose that Bailey’s sells ice cream sundaes, and the defendant has said the chocolate sauce in Bailey’s ice cream sundaes is poisonous. Now, the chocolate sauce does not compete with the defendant because he’s an ice cream parlor, but, nonetheless, he is directly affected by the statement that he is suing about.

He is, therefore, different from the other suppliers who might have supplied Bailey’s with cushions, heat, electricity. But shouldn’t at least that supplier of chocolate sauce have the standing to bring a claim against the ice cream parlor that competes with Bailey?

. . .

JUSTICE ALITO: All right. So, in Justice Breyer’s hypothetical about the soda fountain that sells ice cream with chocolate sauce and there is a statement that the chocolate sauce is poisonous, if the effect of that is to drive out of business a little company that manufactures ice cream that’s used there, that company would not have standing?

MR. JONES: I think if it’s not being talked about in that case, that company probably would not have standing. But the fact that the false advertisements in that case were about the chocolate sauce shows that — why the chocolate maker needs to have standing. That maker has different incentives vis-à-vis the person who is operating the Bailey’s ice cream store.

Bailey’s ice cream store could decide the game’s not worth the candle, and we’re going to stop buying this chocolate, even if all of those advertisements are false. And so the different incentives for the key supplier and the person who is actually within direct competition means that, to further the purposes of the Lanham Act, a party whose goods are misrepresented, either expressly or by necessary implication, needs to have standing.

. . .

JUSTICE BREYER: How do we tie that in? I’m sort of sorry I used that hypothetical because it —

(Laughter) . . .

JUSTICE SCALIA: I am, too, because I’m sick of it.

JUSTICE BREYER: But it illustrates the point. I mean, in my own mind, the standing question is designed to answer: Are you the kind of plaintiff that Congress intended, in this statute, to protect against the kind of injury that you say you suffered? . . .

What do I write to tie that in to the three separate kinds of tests [for standing] that the circuits have talked about? That’s what I can’t quite see — because they talk about the reasonable interest test, they talk about the zone of interest test, they talk about some other kind of test. How do I tie this into that?9

My first experience with Justice Breyer’s colorful hypotheticals was in 2013. I was a Bristow fellow in the U.S. Solicitor General’s Office, a job that came with the huge perk of getting to attend a lot of oral arguments. One of the first I observed was Lexmark International Inc. v. Static Control Components Inc., a case involving a claim of false advertising under the Lanham Act.

I love this excerpt because it encapsulates several of my favorite things about my former boss.

First, he never took himself too seriously. You might not expect a Supreme Court justice to welcome jokes that come at their own expense, but Justice Breyer never minded — in fact, he often seemed to relish those jokes the most.

Second, he had enormous affection for his colleagues. Justice Breyer’s close friendship with Justice Thomas has been oft-discussed for decades now (they were also fittingly close in proximity, given their seats next to one another on the bench). But the Justice’s warm relationships extended well past that one, and his repartee with Justice Scalia during the Lexmark argument was just one of many the two shared. Justice Scalia passed away while I was clerking at the Court, and I will never forget walking into Justice Breyer’s office a few days later to find him staring blankly into space. “I’m really going to miss Nino,” he said, so softly I could hardly hear him.

Third, immediately following his wisecracking with Justice Scalia in Lexmark, Justice Breyer returned to pressing the advocate about what an opinion favoring the lawyer’s client would say. “What do I write?” the Justice implored. This was a question Justice Breyer asked often at argument — what exactly should an opinion in your favor say? It was a question that was always at the forefront of his mind. Crafting opinions thoughtfully mattered to the Justice because he understood that our democracy is sustainable only so long as its citizens respect the decisions that the Court issues. Justice Breyer cared deeply about ensuring that the opinions he wrote made sense to anyone who read them, lawyers and nonlawyers alike.

On Justice Breyer’s last day on the bench, the Chief Justice commemorated his departure. The Chief Justice was audibly choked up, acknowledging Justice Breyer’s “downright silly” hypotheticals, as well as his more “challenging and insightful” questions. That lump in the Chief’s throat is one many of us share. The Court will not be the same without Justice Breyer.

— SARAH BOYCE is deputy solicitor general at the North Carolina Department of Justice.

Footnotes: