Preserving the Future of Juries and Jury Trials

Vol. 109 No. 2 (2025) | Communicating to the People | Download PDF Version of Article

The American justice system has evolved at a dizzying pace over the past several years.1 COVID-19 spurred many changes, especially the rapid implementation of remote technologies. Other influences predated the pandemic, including shifts in political and social attitudes related to racial justice and income inequality.

In 2020, the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) launched the Just Horizons initiative to help courts prepare for possible futures that may be only dimly seen or are still unknown.2 As such, Just Horizons involved thinking concretely about the proper role of courts in democratic governance, exploring how they can leverage societal changes to strengthen their function and build resilience against future societal changes that might undermine it. The Just Horizons project employed a technique called “strategic foresight,” a structured and systematic way of exploring plausible futures to anticipate and better prepare for change.3 Rather than predicting the future, strategic foresight examines existing societal trends to imagine plausible futures that may lie ahead. The goal is to identify emerging opportunities, strengthen resilience, and prepare for potential challenges.

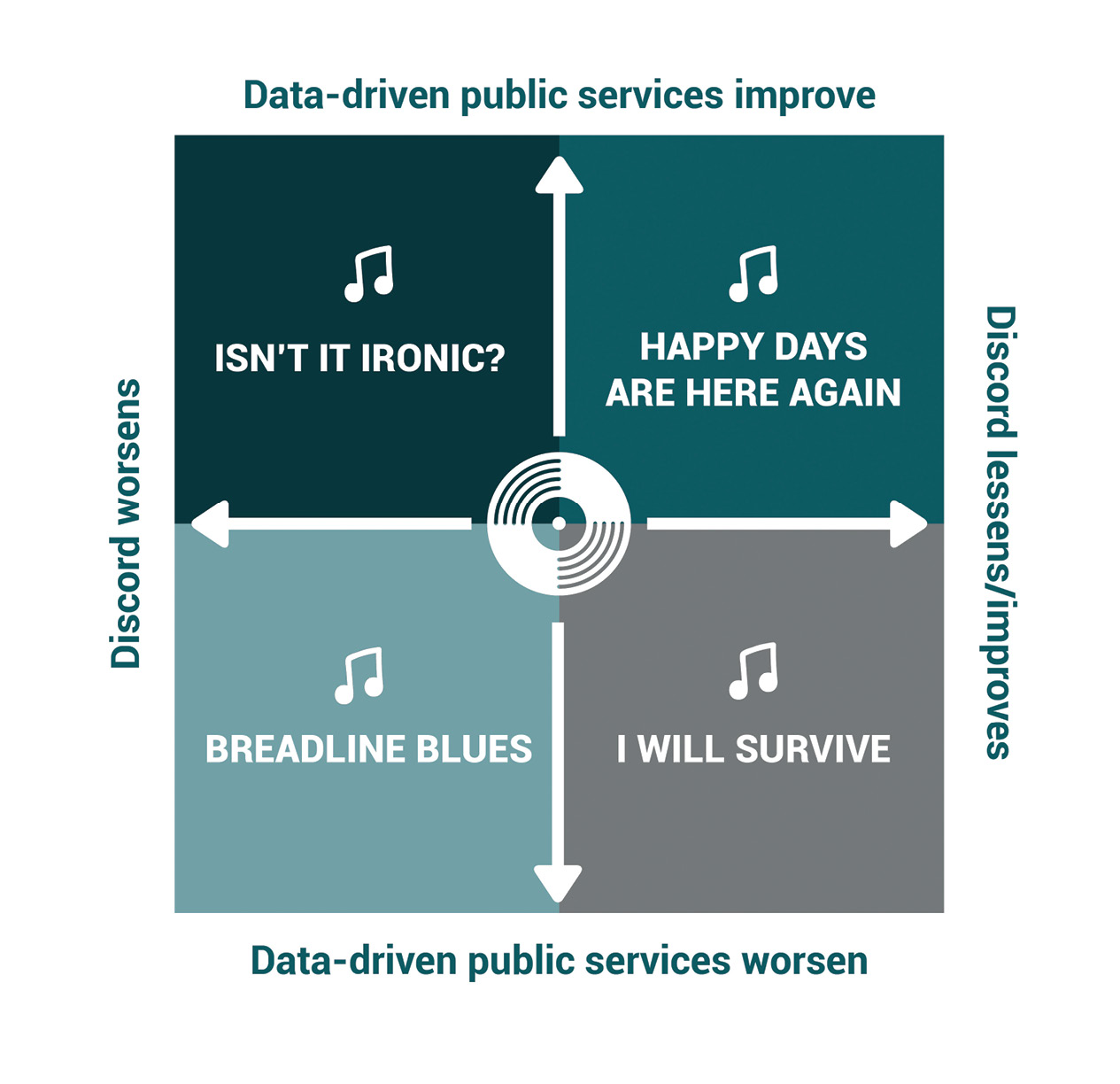

A first step in this approach is conducting environmental scans to identify external trends and forces of change. After considering more than a dozen societal trends, Just Horizons focused on two — data-driven public services and sociopolitical discord — to imagine plausible futures for the courts. The project considered scenarios in which courts either embraced or failed to adopt data-driven policies and in which sociopolitical discord either increased or decreased. Juxtaposing these two trends created four distinct scenarios for plausible futures, for which Just Horizons imagined details of court operations. Each future was labeled with a well-known song title to describe its effect (Figure 1). The two trends are not necessarily related in any way, and for the purpose of the Just Horizons project, each future was an equally plausible result of the trends.

Figure 1. Four plausible future scenarios for juries and jury trials.

The initiative inspired a follow-on project focused on juries and jury trials — a relatively narrow area of court operations but one that has an outsized impact on public trust and confidence in the justice system. In 2024, NCSC launched Preserving the Future of Juries and Jury Trials, a project that built on Just Horizons’ methodological foundation of strategic foresight and its premise that data-driven public services and sociopolitical discord have the greatest potential impact on court operations. For this project, NCSC imagined how these trends would affect juries and jury trials in each of the scenarios.

The Four Scenarios

The “Happy Days Are Here Again” scenario imagined a world in which juries and jury trials were marked by a transformative embrace of technology, collaboration, and civic engagement. In that future, data-driven systems, streamlined electronic processes, and innovative partnerships increased juror participation, improved juror diversity, and bolstered public trust in the justice system. However, as public-sector services gained more public confidence, people — including those in the private sector — gradually lost interest; this complacency made it difficult to maintain adaptability and equity in these advancements.

The “Isn’t It Ironic?” scenario highlighted a future in which data-driven public services were successfully implemented, but sociopolitical discord nevertheless worsened over time. In this scenario, juries and jury trials were buffeted by the tension between technological advancements and persistent challenges to fairness and public trust.4 Innovations such as real-time scheduling apps, specialized judicial roles, and AI-assisted processes streamlined and modernized the justice system, but fears of bias, disinformation, and manipulation fueled public skepticism and mistrust.

The third and fourth scenarios envisioned futures in which courts failed to embrace data-driven public services. In the “Breadline Blues” scenario, juries and jury trials faced significant challenges as economic hardships, logistical difficulties, and declining juror participation led to smaller, less representative jury pools and a growing reliance on expedited or alternative trial methods. These compromises, coupled with the rising prevalence of fabricated digital evidence and strained public trust, threatened the accessibility, impartiality, and legitimacy of jury trials in a fractured and resource-depleted society.

Finally, the “I Will Survive” scenario envisioned a future of juries and jury trials in which privatization and community-specific justice systems replaced traditional juries and public adjudication. Wealthy individuals favored private arbitration and juries curated by the private sector, while affinity-based or isolated communities developed localized systems that prioritized shared cultural values over national standards. This balkanization led to diminished diversity (primarily in terms of demographics and socio-economic status), increased groupthink, and inconsistent notions of fairness, as communities emphasized self-governance and rejected broader legal frameworks.

In February 2024, NCSC invited a broad array of justice system stakeholders to participate in a two-day workshop that considered the potential impact of these scenarios on the American justice system. Stakeholders were state and federal trial and appellate court judges; court administrators, including jury commissioners; prosecutors; plaintiff, civil defense, and criminal defense attorneys; representatives from community and business groups; and scholars who study juries and jury trials in the U.S. justice system through the lens of a variety of academic disciplines.

In a series of workshop discussions, stakeholders examined these possible futures and identified fault lines (called “vulnerabilities” in the parlance of strategic foresight methods) that these futures have in common and that, if left unaddressed, threaten the resilience of juries and jury trials. The stakeholders ultimately identified four distinct vulnerabilities: (1) lack of public education and civic engagement in jury service; (2) failure to focus on the juror-centered experience; (3) institutional incapacity and disincentives for jury trials; and (4) the misalignment between values and operational practices. They then proposed strategies to address each vulnerability.

This article draws on the stakeholder discussions to explain the significance of these vulnerabilities for the future of juries and jury trials, and, more pointedly, why it matters for the long-term health of the U.S. justice system.

Foster Public Education and Engagement in Jury Service

One of the most pressing vulnerabilities facing the future of juries and jury trials is the lack of public education and engagement regarding the jury system and jury service. For many, jury duty is seen as an inconvenience or a burden — something to be avoided rather than a privilege of citizenship and a vital civic responsibility. A major symptom of this vulnerability is the dramatic increase in nonresponse and failure-to-appear (FTA) rates reported by courts nationwide.

In 2007, state courts reported that 9% of prospective jurors failed to respond or appear for jury service.5 By 2019, this rate had increased to 14%, and by 2022, it had risen to 16%.6 In two-step jury systems, in which the court prequalifies the pool of prospective jurors before randomly summoning qualified jurors for service, the nonresponse rate for qualification questionnaires was 17% and 22% in 2019 and 2022, respectively.7 Many factors contribute to nonresponse and FTA rates, not the least of which is unreliable postal service delivery.8 A substantial factor, the stakeholders concluded, is a fundamental lack of public understanding about jury service and its role in the justice system, which is rooted in a broader decline in civics education.

Historically, jury service has been promoted as a cornerstone of democratic participation — a means by which ordinary citizens can directly influence the administration of justice. This view posits that jury duty is not just an obligation but a powerful exercise of democracy in action. Serving on a jury enables citizens to reflect their community’s values in the deliberative process, thereby preventing injustice and ensuring that justice aligns with the moral and ethical standards of the populace. Yet in recent years, traditional appeals to civic duty have grown increasingly less persuasive, particularly in the face of rising partisanship and social division, according to the stakeholders’ conclusions. A 2024 survey of prospective jurors in California, for example, found that one-quarter disagreed or were neutral about the proposition that jury trials are an important part of the U.S. justice system. One-third disagreed or were neutral that jury service is an essential civic duty. And less than half agreed that jury verdicts are fair to litigants.9

The stakeholders concluded that this landscape of citizen disenchantment, amplified by social media, has made it more challenging to convey the importance of jury service in a way that resonates with diverse audiences. Moreover, the decline in funding for civics education in K-12 education has left many citizens ill-prepared to understand the significance of their role as jurors.10 Engaging the public in a meaningful way requires a nuanced approach that acknowledges the varied experiences and perceptions of young people, communities of color, and working-class individuals, each of whom has unique concerns about the jury system that need to be addressed in culturally relevant ways.

While schools can serve as a conduit for educating youth, outreach to more dispersed groups may require creative strategies, such as public service announcements during commuting hours or more sustained outreach to the business community to support employees summoned for jury service.11 Additionally, simple lectures about the importance of jury service and civic duty may not be as impactful as providing real-world examples of how this aspect of the democratic system and the empowerment of ordinary citizens benefit the local community. Helping individuals understand the jury system and its principles in a concrete way can be achieved through town hall meetings hosted by local judges, public oral arguments, mock jury trials, and other initiatives that demystify the process and allow citizens to experience it before serving on a jury.

Effective public education and engagement strategies must also take into account the realities of today’s technology-driven world. Traditional forums for social and educational engagement have largely shifted online. Reaching the public now requires innovative, attention-grabbing content that can compete with the overwhelming amount of information available on social media. Outreach efforts also need to be inclusive, providing information in multiple formats and languages to engage a wide variety of communities, cultures, and non-English-speaking populations who may be future jurors, even if they are not presently qualified for jury service.

Courts, with their unique ability to convene diverse audiences, must lead efforts to educate and engage the public about the importance of jury service. However, the task is far too large for courts to accomplish on their own. Businesses, educators, and others share responsibility for addressing this vulnerability. Moreover, the civil and criminal bars should convey confidence in juries and jury trials, both as a general proposition and as a viable option for clients to fairly resolve cases. The business community, which benefits from a civically engaged workforce, should also play a substantial role in promoting jury service among its employees. Educators, who shape the civic knowledge and attitudes of future generations, must ensure that civics education is not neglected in favor of other subjects. Cultural, civic, religious, and other groups also have a voice in addressing these profound issues.

Focus on the Juror-Centered Experience

The United States has made great progress in expanding eligibility criteria for jury service since its founding, when only white, male property owners were permitted to serve.12 Ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments extended the franchise to formerly enslaved men. In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Taylor v. Louisiana that the exclusion of women from jury service violated the Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury.13 Today, the right to serve as a trial juror is generally available to adult citizens who are legal residents of the geographic community in which they are summoned.14 Some states have extended eligibility to convicted felons who have completed their sentences.15 In New Mexico, persons with limited English proficiency are eligible to serve with assistance from court-provided foreign-language interpreters.16

Historical legal restrictions on eligibility have been repealed over time, and operational practices that erected barriers to jury service for large segments of the population have also been reformed. The “key-man” system — in which local jury commissioners individually vetted prospective jurors based on highly subjective criteria such as public stature — was replaced by a system of random selection from broad-based juror source lists.17 These reforms have been rightly lauded as promoting the broadest possible participation in jury service.

Yet, for all the rhetorical praise of juries and jury trials, the justice system too often fails to prioritize jurors’ ability to serve. A 2022 study of juror compensation, for example, found that the average per diem paid to jurors on the first day of service was a measly $16.61 — roughly 20% of the daily per capita income in the United States.18 In many urban areas, this amount does not even cover out-of-pocket expenses for transportation, parking, meals, or childcare. At the same time, the proportion of private employers who compensate employees summoned for jury service has declined, forcing jurors to bear the financial burden of jury service.19 Jurors who can afford to appear for jury service often find themselves languishing in crowded jury assembly rooms for long periods without ever being called to a courtroom for jury selection. On average, only one-quarter of jurors summoned for jury service reach jury selection, are questioned during jury selection, and are either sworn in as trial jurors or alternates, removed for cause or hardship, or removed by peremptory challenge.20

The comparatively few individuals empaneled as trial jurors receive little support from judges and attorneys to aid their decision-making during trial and deliberations. Although judges and lawyers describe the evidence and law in most jury trials as moderately complex, jurors were permitted to submit written questions to witnesses in only 16% of trials.21 In 38% of jury trials, jurors were not given written copies of jury instructions during final jury deliberations.22 They were not even permitted to take notes in 32% of trials.23 Submitting questions, receiving written jury instructions, and taking notes have been shown to enhance juror understanding and attentiveness.24 Finally, approximately 10% of jurors experience high levels of stress or anxiety due to the nature of the evidence and testimony they hear at trial, but only a handful of courts have resources in place to support jurors’ mental health following service.25

The collective failure to focus on the juror-centered experience is a significant vulnerability for the future of jury trials, with consequences extending beyond the individual juror. When jurors leave the courthouse with negative impressions, those perceptions can spread through their communities, discouraging others from participating in future jury service. This, in turn, shrinks the pool of willing jurors and risks creating a jury system that is less representative of the community, undermining public trust in the justice process.

Addressing this vulnerability requires a fundamental shift in how the justice system approaches jury service. Instead of viewing jurors as passive observers of trial proceedings, judges and lawyers should recognize them as central figures in the process who deserve respect and support throughout their service. Furthermore, courts must consider the future impact that today’s jurors have on public perceptions of jury service. This shift involves rethinking everything from the moment a potential juror receives a summons to any posttrial support they may need, especially in cases involving traumatic testimony or evidence.26

Increase Capacity and Incentives for Jury Trials

In 2019, state and federal courts conducted an estimated 128,972 jury trials, continuing a downward trend in the rate of jury trials that was first recognized in the late 1990s.27 The rise of plea bargaining and alternative dispute resolution has dramatically reduced the frequency of jury trials, particularly in criminal cases. Today, only a small percentage of federal and state cases are resolved by a jury, with the vast majority being settled through guilty pleas or other nontrial methods.28 This trend reflects deeper structural issues within the legal system, especially a lack of institutional capacity as well as significant disincentives for lawyers to take cases to trial and for judges to prioritize trials over nontrial dispositions.29

Jury trials are the most time- and labor-intensive events that can occur in the life of a case, making them extremely expensive for both litigants and taxpayers. They also compete for judges’ and lawyers’ time and attention on large caseloads, which have increased substantially without commensurate increases in the number of judges, prosecutors, criminal defense attorneys, and even courtrooms. The resulting shift to plea agreements, settlements, and other nontrial dispositions is viewed as necessary to keep the justice system from grinding to a complete halt.

Changes to state and federal rules of civil procedure introduced pretrial barriers that litigants must overcome before proceeding to trial, including summary judgment, motions to dismiss for lack of legal sufficiency, and restrictions on the admissibility of expert testimony.30 Contractual requirements for binding arbitration in standard consumer agreements often prevent civil disputes from being filed in court.31 In criminal cases, the disincentives for pursuing a jury trial are even more stark.

Defendants who choose to go to trial often face the prospect of much harsher sentences if convicted — a phenomenon known as the “trial penalty.”32 This can be a powerful deterrent, particularly when coupled with the financial burdens associated with a trial, such as court fees, fines, and the costs of legal representation. For many defendants, pleading guilty to a lesser charge, even if they believe themselves innocent, is seen as the safer and more practical option.33

More fundamentally, the legal profession itself is facing a capacity crisis. Many newer attorneys have little to no experience in jury trials, and opportunities for young lawyers to gain trial experience have become increasingly rare. Without this foundational experience, fewer attorneys feel comfortable taking cases to trial, further perpetuating the decline in jury trials.34 The implications of this trend are profound. As fewer cases go to trial, the skills and experience necessary to conduct jury trials are eroding within the legal profession. This creates a feedback loop where the lack of experience leads to fewer trials, which in turn reduces opportunities for gaining that experience.35 Additionally, the lack of trial experience among lawyers means that when cases do go to trial, they may not be handled as effectively, potentially leading to less favorable outcomes for clients and, at least indirectly, undermining public confidence in the jury system.

Addressing this critical vulnerability requires a multifaceted approach. Law schools, bar associations, and the courts must work together to ensure that future generations of lawyers are equipped with the skills and experience necessary to conduct jury trials effectively. This includes not only enhancing trial advocacy training and clinical trial opportunities, as well as externships with trial opportunities in law schools, but also creating more opportunities for young lawyers to gain trial experience early in their careers.

Structural reforms and additional funding are also needed to reduce the disincentives for pursuing jury trials.29 This could involve increasing the number of judgeships, providing greater financial support for public defenders and legal aid organizations, increasing funding for trial preparation, and reconsidering sentencing guidelines that disproportionately penalize those who exercise their right to a jury trial.

Align Values of Trial by Jury With Operational Practices

A significant and often overlooked vulnerability within the jury system is the disparity between the values that the system is intended to uphold and the actual practices that occur in court. Misalignment between ideals and reality threatens the integrity of jury trials and, by extension, the broader justice system. Addressing this vulnerability is challenging because it requires a willingness to confront sometimes uncomfortable truths about how the system operates and the impact of these practices on both jurors and litigants.

At its core, the jury system serves several key functions. It acts as a bulwark against tyranny. It confers legitimacy on the law. It injects community values into the adjudicative process. It educates jurors — and, by extension, the broader public — about the rule of law. It provides a baseline for judges, lawyers, and litigants to assess the costs and benefits of nontrial dispositions. And, ultimately, it resolves disputed issues of fact to decide cases that have resisted resolution by other means. In serving these functions, the jury embodies the United States’ fundamental values of civic participation, due process, equal protection, promoting the common good, protecting individual liberty and dissenting voices, and holding wrongdoers accountable.36 However, there is a longstanding and growing recognition that these ideals are not always realized in practice, particularly when it comes to ensuring that juries are representative of the communities they serve, trial procedures support jurors’ ability to serve and make informed decisions, and the right to a jury trial remains accessible to all.37

Like other areas of legal culture, jury operations and trial practices tend to become firmly entrenched over time. They are often designed to meet the needs of internal stakeholders who may be reluctant to make changes to systems that are working “good enough,” especially when proposed improvements require adjustments in other areas of court operations or threaten to destabilize well-established power structures. Inertia is a powerful force that often prevents reform efforts from taking root until external pressure, such as legislation or technology, compels change.

In the example of representative jury pools, many of the “easy fixes” for underrepresentation, such as replacing key-man systems with random selection from broad-based master jury lists, were accomplished decades ago. Today’s reforms — including increased juror compensation, shorter service terms, and especially stronger public education and outreach — require sustained investment in both concrete resources and behavioral and attitudinal change. Similar dynamics shape initiatives to support informed juror decision-making and to preserve litigants’ meaningful right to trial by jury.

Bridging the gap between values and practices requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders in the justice system — courts, bar associations, law schools, and business and community organizations — to acknowledge existing shortfalls. That work should start by identifying objective performance measures tied to the vulnerabilities identified in its report on the Preserving the Future of Juries and Jury Trials project.

At a high level, juror response and appearance rates may serve as reasonable measures of public engagement with jury service, while the proportion of hardship-based excusal requests from jurors may reflect how effectively the justice system reduces barriers to service. Similarly, trial rates may indicate how comfortable litigants are taking their disputes to trial, while the time from filing to trial may reveal a jurisdiction’s capacity to conduct jury trials.

Conclusions

Stakeholders who participated in the workshop for the Preserving the Future of Juries and Jury Trials project revealed a shared concern: The challenges facing juries and jury trials are not isolated but part of broader structural threats to U.S. democracy and the rule of law. These vulnerabilities, shaped over decades by diverse external pressures, underscore the need for proactive measures to protect the constitutional right to trial by jury. Just as importantly, they expose parallel weaknesses across the justice system that, if left unaddressed, risk eroding public trust and the system’s fundamental integrity.

Addressing these vulnerabilities demands a unified effort from all sectors of society — judges, lawyers, educators, business leaders, and community organizations. By working together, stakeholders can transform these challenges into opportunities to strengthen both the justice system and the communities it serves. A detailed report, including examples and strategies to address each identified issue, is available at https://duke.is/futureofjuries. We encourage readers to join this vital conversation by sharing their experiences and insights to help foster collective action that safeguards and revitalizes the justice system for generations to come.

PAULA HANNAFORD-AGOR is director emeritus of the National Center for State Courts’ Center for Jury Studies. During her 32-year career, she conducted research and provided technical assistance and education to judges and court staff on jury system management and jury trial procedure.

1 The Preserving the Future of Juries and Jury Trials project was supported by Grant No. 2019-YA-BX-K001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA). BJA is a component of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office of Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the U.S. Department of Justice or the National Center for State Courts.

2 Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts., Just Horizons: Charting The Future of the Courts, vi (2022), https://issuu.com/statecourts/docs/justhorizons.

3 For an overview of strategic foresight methods, see Kevin Kohler, Strategic Foresight: Knowledge, Tools & Methods for the Future (Sept. 2021), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355046926_Strategic_Foresight_Knowledge_Tools_and_Methods_for_the_Future.

4 See Nicole Gillespie et al., Trust, Attitudes, and Use of Artificial Intelligence: A Global Study 2025 (2025), https://doi.org/10.26188/28822919.

5 Gregory E. Mize et al., State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: A Compendium Report 22 (2007), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/112/rec/1.

6 Paula Hannaford-Agor & Morgan Moffett, 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Performance Measures for Jury Operations 4 (2024), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/366/rec/34.

7 Id.

8 See Paula Hannaford-Agor et al., Why Won’t They Come? A Study of Nonresponse and Failure-to-Appear in Harris County, Texas 12 (2023), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/388/rec/27; Robert G. Boatright, Improving Citizen Response to Jury Service: A Report with Recommendations 36 (1998).

9 Juror opinion responses are based on surveys administered to prospective jurors in the superior courts of seven California counties in 2024 as part of an evaluation of the impact of increased juror compensation on citizen participation in jury service (on file with NCSC). These responses by prospective jurors were significantly lower than judge and lawyer responses to identical questions posed in the 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts. See Hannaford-Agor & Moffett, supra note 6; see also Paula Hannaford-Agor & Morgan Moffett, 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Criminal Jury Trials 16 (2023), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/384/rec/9; Paula Hannaford-Agor et al., State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Civil Jury Trials 13 (2024), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/393/rec/15.

10 See Suzanne Spaulding et al., Civics at Work: Implementation Guide for Businesses 1 (2022), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/220923_Spaulding_CivicsAdults_GuideforBusinesses.pdf?LXRCWENb3Ixtf6PRlPB6PRTMnPHzenP0.

11 See id.

12 See William S. Brackett, The Freehold Qualification of Jurors, 29 U. Pa. L. Rev. 436, 444 (1881), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol29/iss7/2/.

13 Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 538 (1975).

14 See David B. Rottman & Shauna M. Strictland, State Court Organization 2004, 218 (2006), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sco04.pdf.

15 See James M. Binnall, Twenty Million Angry Men: The Case for Including Convicted Felons in Our Jury System 19-20 ( 2021).

16 See N.M. Const. art. VII, §3 (“The right of any citizen of the state to vote, hold office or sit upon juries, shall never be restricted, abridged or impaired on account of religion, race, language or color, or inability to speak, read or write the English or Spanish languages except as may be otherwise provided in this constitution. . . .”).

17 Paula Hannaford-Agor & Nicole L. Waters, Tripping Over Our Own Feet: In Jury Operations, Two Steps Are One Too Many, 25 Ct. Mgr. 49 (2011).

18 Brandon W. Clark, Juror Compensation in the United States 7 (2022), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/338/rec/1.

19 Contrast, e.g., Juror opinion responses, supra note 9 (on file with NCSC) with Paula Hannaford-Agor, Increasing the Jury Pool: Impact of the Employer Tax Credit 4-5 (2004), https://cdm16501.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/73.

20 See Hannaford-Agor & Moffett, supra note 6, at 9.

21 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Criminal Jury Trials, supra note 9, at 8; 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Civil Jury Trials, supra note 9, at 9.

22 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Civil Jury Trials, supra note 9, at 10.

23 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Criminal Jury Trials, supra note 9, at 9; 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Civil Jury Trials, supra note 9, at 9.

24 See B. Michael Dann & Valerie P. Hans, Recent Evaluative Research on Jury Trial Innovations, 41 Ct. Rev. 12, 13–17 (2004).

25 In federal court, the trial judge is authorized to make counseling available to trial jurors through the federal Employee Assistance Program. See Paula Hannaford-Agor, Jury News: A New Option for Addressing Juror Stress? 1 (2011), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ctadmin/id/1928/rec/26. In 2022, Massachusetts implemented a statewide juror counseling program, and some local courts have implemented programs by tapping into resources for local first responders. See Nat’l Jud. Task Force to Examine State Courts’ Response to Mental Illness: Trauma-Informed Practices and Jurors 1 (2022), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/345/rec/1.

26 See Nat’l Conf. St. Ct. Admin., Citizens on Call: Responding to the Needs of 21st Century Jurors 27-31 (2023), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/360/rec/1.

27 See Paula Hannaford-Agor & Morgan Moffett, 2023 State-of-the-States Survey of Jury Improvement Efforts: Volume and Frequency of Jury Trials in State Courts 3 ( 2024), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/juries/id/365/rec/ (noting that state courts conducted an estimated 125,222 in 2019); U.S. Cts., Table J-2 — U.S. District Courts — Grand and Petit Jurors Statistical Tables for the Federal Judiciary (2019), https://www.uscourts.gov/data-news/data-tables/2019/12/31/statistical-tables-federal-judiciary/j-2 (stating that federal courts conducted 3,750 jury trials in 2019); Mize et al., supra note 5, at 7 (indicating that state and federal courts conducted an estimated 154,021 jury trials in 2007). In 2004, Professor Marc Galanter published the keynote essay on this trend for the 2003 Symposium on the Vanishing Trial, documenting steady declines in the number of jury trials from 1962 to 2002. See Marc Galanter, The Vanishing Trial: An Examination of Trials and Related Matters in Federal and State Courts, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 459, 459 (2004).

28 See Hannaford-Agor & Moffett, supra note 27, at 2.

29 See Shari Seidman Diamond & Jessica M. Salerno, Reasons for the Disappearing Jury Trial: Perspectives from Attorneys and Judges, 81 La. L. Rev. 119, 123–126 (2020).

30 See Paula Hannaford-Agor, Jury System Management in the 21st Century: A Perfect Storm of Fiscal Necessity and Technological Opportunity, in The Improvement of the Administration of Justice 505, 506–511 (Peter M. Koelling ed., 8th ed. 2016).

31 See id. at 507.

32 See Seidman Diamond & Salerno, supra note 29, at 126.

33 See id.

34 See Tracy Walters McCormack & Christopher J. Bodner, Honesty Is the Best Policy: It’s Time to Disclose Lack of Jury Trial Experience, Univ. Tex. L., Pub. L. Rsch. Paper No. 151 1, 18 (2009).

35 See Beth Schwartzapfel et al., The System: The Truth About Trials, The Marshall Project (last updated Nov. 4, 2020), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/11/04/the-truth-about-trials.

36 See generally Andrew G. Ferguson, Why Jury Duty Matters: A Citizen’s Guide to Constitutional Action (2012).

37 See Mary R. Rose et al., Jury Pool Underrepresentation in the Modern Era: Evidence from Federal Courts, 15(2) J. of Empirical Legal Stud. 1, 21 (2018).