Possible and Needed Reforms in the Administration of Civil Justice in the Federal Courts

Vol. 100 No. 1 (2016) | 100 Years of Judicature | Download PDF Version of Article

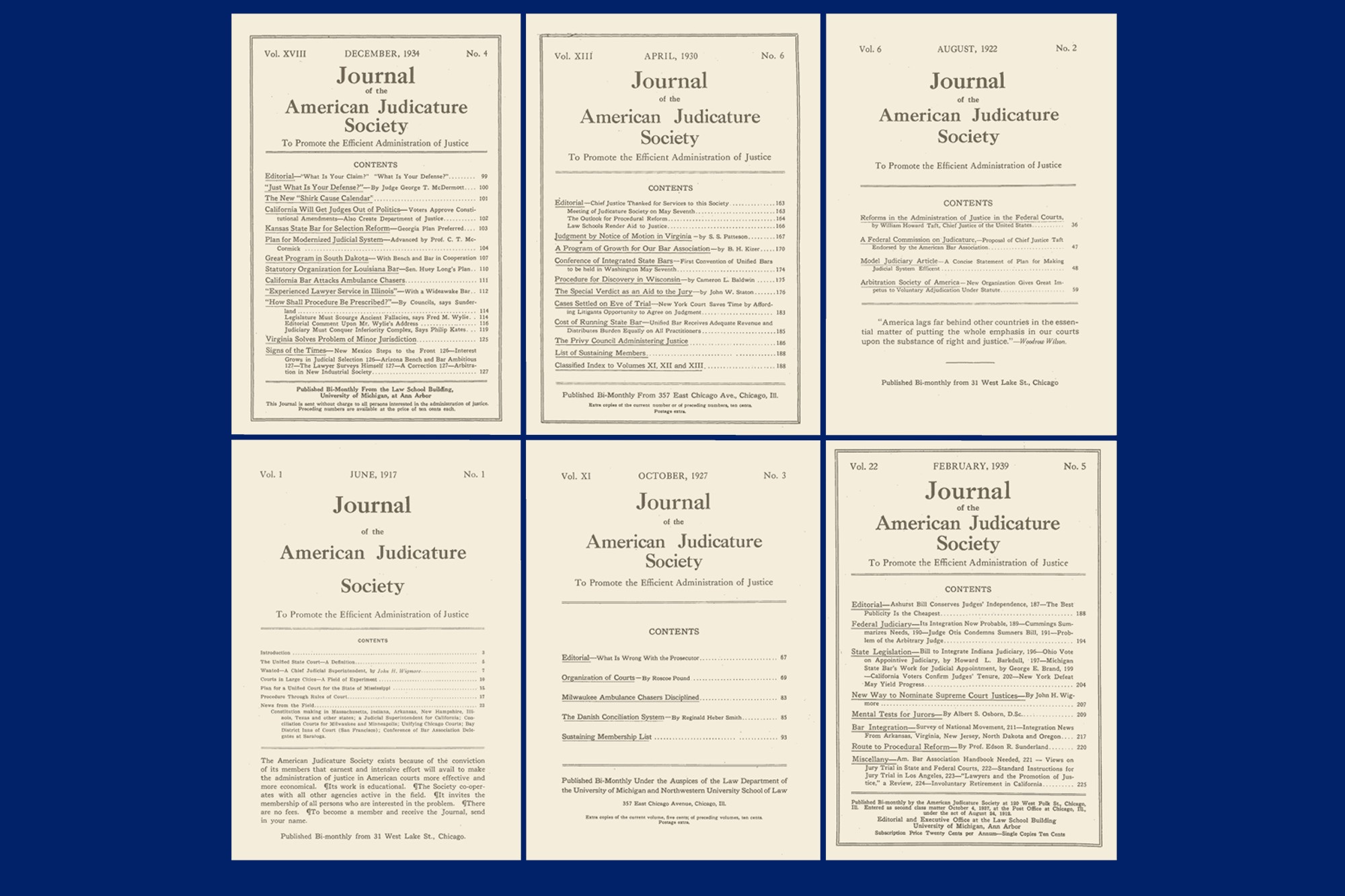

This year marks the 100th volume of Judicature.

To celebrate, each edition of this centennial volume will feature reprints of articles from the journal’s first 100 years. We’ve edited for length only — the turns of phrase and quirks of grammar from years past are just part of the fun of exploring 100 years’ worth of a continuing conversation about how best to advance the administration of justice in the United States. As we scour Judicature’s first 100 volumes (see the full HeinOnline archive here), we see that many of the issues we face today are but the latest visits of challenges that have long come to call on the judiciary — which is perhaps both comforting and dismaying at once. We also are reminded of the great service the American Judicature Society provided to the judiciary by providing a forum for discussion of these important issues for nearly 100 years.

The following excerpt is from a speech by Chief Justice William Howard Taft; it was published in August 1922, in volume six of what was then known as the Journal of the American Judicature Society. Taft had already served as president of the United States (1909-1913), and at the time of this writing was early in his tenure as the 10th Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court (1921-1930). Here, addressing the American Bar Association, Taft advocates for reform in the administration of civil justice by merging the courts of law and equity. He supports his proposal by highlighting the successes of the courts of England and Wales, where law and equity had been combined since the late-19th century. This system, Taft explains, fostered judicial efficiency and traditional notions of fairness and justice.

Taft published another article in Judicature in 1925. He is among the six of the last eight chief justices who have contributed to the journal: Charles Evans Hughes,1 Harlan F. Stone,2 Fred M. Vinson,3 Earl Warren,4 and Warren E. Burger5 also published pieces in Judicature during their terms on the Supreme Court.

— Editors

Possible and Needed Reforms in the Administration of Civil Justice in the Federal Courts6

BY WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

I hope you feel in a proper state of mind this morning, in view of the roof under which you are gathered. I don’t know any reason why the distinction was made by which Lord Shaw of Dunfermline7 should speak in a place where athletic contests had theretofore been had, and I should be assigned to this sacred structure. It was doubtless because they knew that Lord Shaw could be trusted anywhere. I am sorry that we have not had the benefit of this fine church auditorium for all the sessions. I feel in speaking here as if I were enjoying an undue privilege, as if it were denying to others the equal protection of the law, not to give them the same opportunity. However, I shall need your prayers and all your self-restraint to keep your attention to what I have to present to you this morning, because it is going to be dry to the point of satisfying the Anti-Saloon League.

For many years, the disposition of business in the Federal courts of first instance was prompt and satisfactory. This was because the business there was limited, and the force of judges sufficient to dispose of it; but of recent years the business has grown because of the tendency of Congress toward wider regulation of matters plainly within the Federal power which it had not been thought wise theretofore to subject to Federal control. More than that, the general business of the country, and the consequent litigation growing out of it, has increased, so that even in fields always occupied by the Federal courts, the judicial force has proved inadequate. In this situation, the war came on, statutes were multiplied, and gave a special stimulus to Federal business. Since the war there has been a great increase of crimes of all kinds throughout the country. This within the federal jurisdiction has included depredations on interstate commerce, schemes to defraud in which are used facilities furnished by the general government.

Then under the inspiration of the war, traffic in intoxicating liquors was forbidden, and under the same inspiration the 18th Amendment was passed and the Volstead law was put upon the statute books. Prosecutions under this law alone have added to the business in the federal courts certainly ten per cent; while cases growing out of the income and other war taxation, out of war contracts and claims against the government, have made discouraging arrears in many congested centers. The criminal business has usually been first attacked, and the effort to dispose of it has in many jurisdictions completely stopped the work on the civil side. . . .

My suggestions are intended to meet the situation as it is, and to secure some method by which the litigation under existing law may be promptly and justly dispatched. The trial of criminal cases in the Federal Courts is not within the score of this paper. . . .

An important improvement in the civil practice in the Federal Courts is one that in my judgment ought to have been made long ago. It is the abolition of two separate courts, one of equity and one of law, in the consideration of civil cases. It has been preserved in the Federal Court, doubtless out of respect for a distinction which is incorporated in the description of the judicial power granted to the Federal government in the Constitution of the United States. But many state courts have years ago abolished the distinction and properly have brought all litigation in their courts into one form of civil action. . . .

The same problem arose in the courts of England and has been most successfully resolved. By the Judicature Act of 1873, Parliament vested in one tribunal, the Supreme Court of Judicature, the administration of law and equity in every cause coming before it. By subsequent acts, the divisions of that Court were reduced to three divisions: (1) the King’s Bench; (2) Equity; (3) and Probate, Divorce and Admiralty, as they are now. They are all merely parts of the same court, but for convenience the suits are brought in those divisions respectively corresponding to the remedies sought. . . .

The Judges Made Responsible

The means by which this reform [the merger of equity and law] was accomplished and the avowed object of the framers of the rules was to effect “a change in procedure which would enable the Court, at an early stage of the litigation, to obtain control over the suit and exercise a close supervision over the proceedings in the action.” Thus could dilatory steps be eliminated, unnecessary discovery prevented, needed discovery promptly had, and the decks quickly cleared for the real nub of the case to be tried. It was first proposed to discard pleadings, but this was abandoned. Suit is begun by service of a writ of summons. Shortly after the appearance of the defendant, a summons for direction is issued to him, at the instance of the plaintiff, requiring him to appear before a Master or Judge to settle the future proceedings in the cause. In the King’s Bench this work is done by Masters. In equity and commercial cases it is usually done by the Judge to whom the case is assigned. The Master or Judge makes an order as to the manner in which the cases shall be carried on and tried. In cases in which the original writ is endorsed with notice that the claim is for a fixed sum as upon a contract, a sale of goods, a note or otherwise, and the plaintiff files an affidavit that there is no defense, the Master may require the defendant to file an affidavit showing that he has a good defense and specifying it, before he may file an answer. If he files no such affidavit, summary judgment goes against him. In other cases, the Master or Judge makes an order, fixing time for pleadings and kind of trial, and no step is therefore taken without application to the Master or Judge, so that the latter supervises all discovery sought, decides what is proper, and requires the parties to lay their cards face up upon the table and the real issue of fact and law is promptly made ready for the trial.

I sat with Sir T. Wills Chitty, the learned and most effective Head Master of the King’s Bench, and saw the solicitors come in, sometimes barristers come before him to shape up the issues, the pleadings and the directions for trial. He knocked the heads of the parties together so that a clear issue between them was quickly reached.

Demurrers are abolished. An objection in point of law may be made either at or after the trial of the facts. Discovery may be had by a mere letter of inquiry from the solicitor of one party to the other and any refusal is at once submitted to the Master or Judge. Should either party object to the orders of a Master, the question can be at once referred to the Judge who is to try the cause and passed on. The pleadings are very simple. They are a statement of claim and an answer. Great freedom is allowed as to joinder of actions and parties and in respect of setoffs and counterclaims. The pleadings are prepared on printed forms prepared for use according to the rules, with details written into the paragraphs. The nature of the claim is stated in a very brief way. A blank paragraph is left in the form for particulars as to the main facts and for reference to documents relied on, copies of which are appended to the pleading. The main facts and the documents upon which each side relies to establish its case or defense are thus brought out by discovery, and all in a very short time. Admissions of important facts are elicited by each side from the other to save formal proof and its expense, on penalty of costs for refusal if the fact proves to be uncontested.

English Procedure Expeditious

The effect of the administration of justice under these rules can be shown in some degree by reference to the judicial statistics of England and Wales for 1919 in the disposition of cases in the High Court of Justice, King’s Bench Division. The summonses issued in the King’s Bench Division in a year amounted to 43,140. In 14,244 cases, judgments were entered for the plaintiff. In 386 cases, judgments were entered for the defendant. In 526 cases other judgments were entered than either for the plaintiff or the defendant, making a total of 15,136 judgments entered in the suits brought. This would leave undisposed of about 28,000 writs of summons issued. This sum represents the suits brought which were abandoned or which resulted in satisfaction of the claim without further proceeding beyond the issuing of the summons. Of the judgments rendered, over 9,000 were entered in default of appearance of the defendant; 756 by default other than in default of appearance. 2,684 judgments were entered as summary judgments under Order 14, because the defendant would not make the necessary affidavit to justify his securing leave to answer. One hundred and forty-one judgments were rendered after trial with a jury. Eight hundred and thirty-six judgments were rendered after trial without a jury. Thirty-five were rendered on the report of the official referee. Of the judgments for defendants, 55 were rendered after trial with a jury, and 309 after trial without a jury. This shows how thoroughly the preliminary steps to the preparing of the issue winnows out the cases and disposes of them without further clogging of the docket.

The speed with which this system disposes of the business was testified to by the New York State Laws Delays Commission twenty years ago. It reported to the Governor in 1903 that 23 judges of the High Court of Judicature in England actually tried twice the number of cases in a year that 41 judges in New York City tried in the same time, and that the difference was due to the operation of summons for directions and the summons for summary judgment. The Report was approved by the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Judge Dillon then being Chairman of the Judiciary Committee of that body. It was sought to introduce this reform for New York City by act of the Legislature providing for fifteen Masters, but it is said to have been beaten by the influence of those who did not wish to abolish the referee patronage in the New York Courts.

The English system is adapted to the conditions prevailing in that country and has been built up on the traditions of the Bench and Bar, which do not have the same force here. Moreover, it is much more applicable to the disposition of the litigation of a great city like New York, Chicago or Philadelphia, as the New York Commission found it to be, than to our Federal Courts of first instance. In the first place, the territorial jurisdiction in England is a compact one, embracing only England and Wales, and in which there are 500 county courts, disposing, under the simplest procedure, of much of the business involving less than £300.8 The branches of the High Court of Judicature to which these rules of procedure apply are centered in London, the judges live there, and while the assizes are held at various towns in England and in Wales, access to London is easy, and the natural result is that the important cases are generally either brought in London or ultimately reach there for their disposition. The division of the profession into barristers and solicitors, and the small number of the active members of the Bar, as compared with our own, make it easy to form an atmosphere of accommodation on part of the counsel toward the court and toward one another, which could hardly exist in the administration of justice in a Federal court covering all or half a state, and involving litigation in which the counsel who appear are engaged in that court in only a small part of their practice. The English barristers only know their clients through the briefs of the case which are handed them on which to conduct the cause in Court. Their fees are fixed in advance and are not contingent. They present the case in an impersonal way and are not tempted to use any other than proper means for the protection of their clients’ interests. This renders much less common efforts at delay and the use of legal procedure to prevent the prompt rendition of justice. More than this, the system of costs in the English courts in which the defeated party is made to pay the expenses of the other side, including solicitors’ and barristers’ compensation, restrains counsel by the fear of penalties always imposed for useless proceedings.

Don’t misunderstand me, that the costs would include a fee of 500 guineas. That is only when you employ one who has climbed to the top of the profession, and if you wish to afford that luxury, you will have to pay for that yourself whether you win or lose.

We could never adopt here the division of the Bar into solicitors and barristers or the English system of costs. But these differences should not prevent our using a great deal of what has proved effective in the English practice to simplify procedure and speed justice in our Federal Courts. The English precedent certainly demonstrates the advantage of having the procedure by Rules of Court, framed by those most familiar with the actual practice and its operation and most acute to eliminate its abuses and defects.

May We Suggest: Judicature International

Footnotes:

- Charles Evans Hughes, An Imperishable Ideal of Liberty Under Law, 25 Journal of the American Judicature Society 99 (1941); Charles Evans Hughes, To Strengthen the Defenses of Democracy, 25 Journal of the American Judicature Society 3 (1941).

- Harlan F. Stone, Dissenting Opinions Are Not Without Value, 26 Journal of the American Judicature Society 78 (1942).

- Fred M. Vinson, The Business of Judicial Administration, 33 Journal of the American Judicature Society 73 (1949).

- Earl Warren, The Administration of the Courts, 51 Judicature 196 (1968); Earl Warren, Delay and Congestion in the Federal Courts, 42 Judicature 6 (1958).

- Warren E. Burger, Roland F. Kirks: A Tribute, 61 Judicature 301 (1978); Warren E. Burger, Deferred Maintenance of Judicial Machinery, 54 Judicature 409 (1971); Warren E. Burger, Agenda for Change, 54 Judicature 232 (1971); Warren E. Burger, The Image of Justice, 55 Judicature 200 (1971); Warren E. Burger, Court Administrators: Where We Would Find Them 53 Judicature 108 (1969).

- An address delivered at the 1922 meeting of the American Bar Association.

- [Lord Shaw served on England’s highest court. In 1922, he visited the United States and Canada as a guest of the American and Canadian Bar Associations.]

- There are 57 County Court judges in England and Wales.