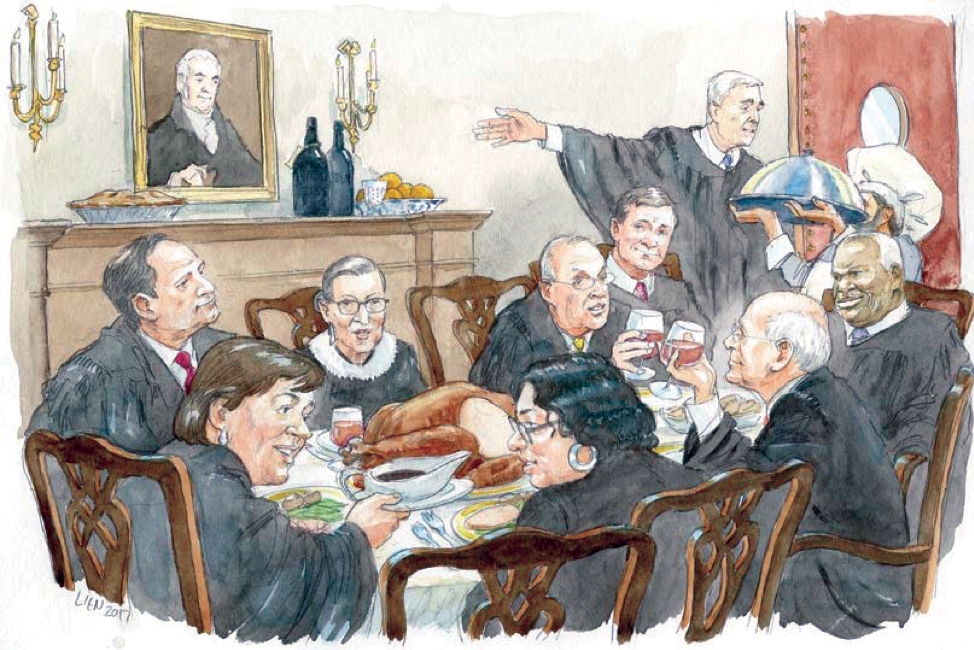

Table for Nine

Vol. 102 No. 3 (2018) | Crowdsourcing and Data Analytics | Download PDF Version of Article

Food traditions have always been important at the Supreme Court, as the justices have purposefully sought occasions to break bread together to reinforce cordiality and cooperation. Their most important culinary tradition is lunching together on days when the Court hears arguments and deliberates cases in conference.

“The lunch break is both a pause in the action and a chance for collegiality,” says retired Justice John Paul Stevens. Justice Sonia Sotomayor says she enjoys the camaraderie: “It’s a wonderful experience.”

Of course, these lunch discussions bar one subject — cases. Frequent topics of conversation include baseball, golf, sports, grandchildren, art exhibits, movies, and favorite books. “We try to avoid controversy,” says Sotomayor, adding the justices “are very guarded about raising topics that might create hostility in the room. That does not mean we do not talk about politics, but not in the great depth we might do in the privacy of our homes. . . . We tell funny stories. Someone will tell about an experience with a child or grandchild. There is just the normal type of conversation that people have who want to get to know each other as individuals rather than justices.”

During the 19th century, there was no lunch break in the Court’s schedule. Oral arguments usually took place five days a week, and the justices heard cases from noon to 4 p.m. From time to time, as the afternoon progressed, the justices, one or two at a time, would slip out of their seats, eat a civilized lunch, and return to the bench. But they did not leave the courtroom. Instead, their personal messengers brought food down from the Senate restaurant and set up small tables behind the bench to serve their individual justices. The audience could not see them eating, but they could very distinctly hear the rattle of the knives and forks, and sometimes the directions of the justices to their messengers.

The justices were mindful of ensuring that there was always a quorum of six on the bench to hear cases. But, on one wintry day in the 1890s, only seven justices made it to the Court, as two were detained by bad weather. When two justices disappeared behind the curtain to eat lunch, the advocate arguing a case that day complained to the chief justice that there was no quorum present. Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller quickly reassured him: “Although you may not see them . . . there are two justices present who can hear the argument, and you may proceed.” Yet attorneys continued to feel frustrated by the rotation of faces on the bench as they declaimed their carefully crafted arguments. Finally, in 1894, Chief Justice Fuller announced from the bench that a recess for luncheon would be taken thereafter, from 2 to 2:30 p.m.

When the new Supreme Court building opened in 1935, it boasted not only chambers for each member of the Court but also a cafeteria that served the justices, Court staff, and visitors, as well as a private dining room with oak paneling and high ceilings where the justices could eat together. The justices eat the same cafeteria food as staff and visitors and pay the same prices.

Attendance at the justices’ group lunch (expanded to an hour in 1969) waxed and waned depending on the cohesion among members of the Court. Some justices only attended for birthdays or special occasions, preferring to dine alone in chambers or with their clerks. When Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was appointed in 1981, she strove to revive the group lunch tradition and persuaded all her colleagues to eat together on days when the Court was in session. Justice Clarence Thomas initially resisted when he was appointed to the Court in 1991: “I was really tired,” he says. “I wanted to get my work done. We had mail pile up. I wanted to spend time with my law clerks. But she kept insisting I join [them] for lunch. She was really sweet but very persistent.” Thomas eventually joined, as did Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer when they were appointed in 1993 and 1994, respectively — also at O’Connor’s insistence. “Now you have a group of people who really enjoy each other’s company,” Thomas says. “It is hard to be angry or bitter at someone and break bread and look them in the eye. It is a fun lunch. It’s just nine people, eight people — whoever shows up — having a wonderful lunch together.”