The Courts’ Views on Ghostwriting Ethics

Vol. 102 No. 3 (2018) | Crowdsourcing and Data Analytics | Download PDF Version of Article

The Courts’ Views on Ghostwriting Ethics Are Wildly Divergent. It’s Time to Find Uniformity and Enhance Access to Justice.

Since the mid-1990s, advocates for increased access to justice have touted unbundled (or limited-scope, or discrete-task) legal services as a means of distributing legal services to those unable to afford full legal representation.1 In response, a growing number of states are adopting court rules permitting lawyers to make limited appearances for particular stages of the litigation, without requiring a motion for leave to withdraw from the case after the service is rendered.2 Another form — possibly the most common — of discrete-task representation is ghostwriting. Attorney Forrest Mosten, the “father” of unbundling, includes in his examples of the practice: “Lawyers can ghostwrite letters or court pleadings for the client to transmit or review and comment on documents the client has prepared, or be engaged only to send a letter on behalf of the client on law-firm letterhead.”3 Surely, ghostwriting existed well before Mosten included it in his examples of unbundled legal services. There is no way of knowing how many, and for how long, lawyers and nonlawyers have engaged in ghostwriting pleadings to assist pro se litigants — indigent or nonindigent. It is reasonable to assume that many lawyers and others have acted as ghostwriters in order to facilitate greater access to the court, rather than for personal gain, because fees for such services — if any are even charged — are much lower than for full representation. Despite the laudable motives of ghostwriters, ghostwriting has historically been considered an illegitimate form of unbundling because of the spate of federal court opinions opposing the practice on ethical and Rule 11-violation grounds.4

This article addresses the current anomalous situation in which federal courts, on the one hand, and the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility and a growing number of state high courts and ethics committees, on the other hand, diverge in their opinions regarding the propriety of ghostwriting. I present the results of a study of 179 federal and state court opinions on the subject. After analyzing the opinions, I conclude with a recommendation to harmonize the federal and state courts’ views on the subject by way of a uniform act or rule that addresses the concerns of those courts that have found ghostwriting to be harmless and furthering access to courts, and those viewing it as unethical, a violation of Rule 11, or a practice that gives pro se litigants an undue advantage over their represented adversaries.

Federal Courts’ Objections to Ghostwriting

The first of three seminal court opinions on ghostwriting, often cited by federal courts, did not raise ethics or a rule violation as the basis of its opposition to ghostwriting.5 The case involved a “habitual litigant” who had filed over 30 lawsuits in five or six years, with the help of a ghostwriter:

[W]e see no good or sufficient reason for depriving the opposition and the Court of the identity of the legal representatives involved so that we can proceed properly with the relative assistance that comes from dealing in the open. . . . [W] e should not be asked to add the extra strain to our labors in order to make certain that the pro se party is fully protected in his rights. . . . [T]his unrevealed support in the background enables an attorney to launch an attack against another member of the Bar . . . without showing his face. This smacks of the gross unfairness that characterizes hit-and-run tactics.6

A second opinion issued a year later involving the same pro se plaintiff held that ghostwriting was, in some unstated manner, “grossly unfair to both this court and the opposing lawyers and should not be countenanced.”7 A third early, oft-cited opinion from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit involving a prisoner seeking a free trial transcript rested its condemnation of ghostwriting on Rule 11: “What we fear is that in some cases actual members of the bar represent petitioners, informally or otherwise, and prepare briefs for them which the assisting lawyers do not sign,” and which the court considered a violation of Rule 11.8 The aforementioned rulings form the basis of most subsequent federal decisions finding ghostwriting unacceptable on ethical and Rule 11 grounds. Later opinions raised an additional “undue advantage” argument:

[The plaintiff’s] pleadings seemingly filed pro se but drafted by an attorney would give him the unwarranted advantage of having a liberal pleading standard applied whilst holding the plaintiffs to a more demanding scrutiny. Moreover, such undisclosed participation by a lawyer that permits a litigant falsely to appear as being without professional assistance would permeate the proceedings. The pro se litigant would be granted greater latitude as a matter of judicial discretion in hearings and trials. The entire process would be skewed to the distinct disadvantage of the nonoffending party.9

The language in the former ABA Model Rules of Professional Responsibility (MRPR) Rule 1.2(c) specifically permits lawyers to “limit the scope of the representation if the limitation is reasonable under the circumstances and the client gives informed consent.” But federal courts have handed down numerous decisions holding that the ghostwriting lawyer breaches a number of ethical duties contained in the current ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct (MRPC) (or its earlier iterations) or state rules of professional responsibility. These include arguments that a lawyer ghostwriter breaches the duty of candor to the tribunal by making false statements to the court.10 Some courts go beyond the violation of the candor requirement, holding that to ghostwrite pleadings is an act of fraud, misrepresentation, or deceit. They cite sections of MRPC Rule 8.4, which states that “[i]t is professional misconduct for a lawyer to: (a) violate or attempt to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct, knowingly assist or induce another to do so, or do so through the acts of another; . . . (c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation; [or] (d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice.”11

Rule 11 Objections

In my 2002 article entitled In Defense of Ghostwriting,12 I argued that none of the federal court’s legal bases for opposing ghostwriting had any merit. On the Rule 11 argument, I first noted that no court rules explicitly prohibit ghostwriting. Neither Rule 11’s language nor its spirit justifies a blanket prohibition on ghostwriting for a pro se litigant absent reasonable grounds to believe that the practice involved intentional deception or an effort to avoid the rules.13 Also, the 1993 Advisory Committee Notes specifically provide that Rule 11 applies not only to signatories of pleadings, but to anyone responsible for a violation of the Rule.14 Thus, absent reasonable grounds to believe the Rule has been violated, I argued there is no justification for invoking Rule 11 as a pretext for barring ghostwriting or compelling disclosure of the ghostwriter’s identity.

Undue Advantage Objection

As to the undue advantage argument, I explained that the liberality rule for review of pro se pleadings15 was no different from the rule (at the time) that no complaint may be dismissed unless “it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief.”16 And, since all complaints must be “construed generously,”17 pleadings — filed pro se or otherwise — are entitled to liberal construction. (The Supeme Court “Twiqbal” opinions altered the general pleading standards, requiring complaints to allege plausible claims.) Moreover, Rule 11 applies to all papers filed in an action, not only the initial complaint. But most concerns raised about ghostwriting deal with the initial complaint. And any shortcomings of a complaint may be amended, so the difference between the pro se liberality rule and the general rule of liberality is “a distinction without a difference. In either case the plaintiff will seek to correct the deficiencies . . . . As such, where is the undue advantage or unfairness to the represented party?”18

As I wrote in my 2002 article:

Practically speaking, . . . ghostwriting is obvious from the face of the legal papers filed, a fact that prompts objections to ghostwriting in the first place. . . . Thus, where the court sees the higher quality of the pleadings, there is no reason to apply any liberality in construction because liberality is, by definition, only necessary where pleadings are obscure. If the pleading can be clearly understood, but an essential fact or element is missing, neither an attorney-drafted nor a pro se-drafted complaint should survive the [dispositive] motions. A court that refuses to dismiss or enter summary judgment against a non-ghostwritten pro se pleading that lacks essential facts or elements commits reversible error in the same

manner as if it refuses to deny such dispositive motions against an attorney-drafted complaint.19

Permitting ghostwriting so that claims and defenses are adequately crafted levels the playing field and streamlines the litigation process by clarifying the issues and reducing the number of dispositive motions and responses.20

Ethics Objections

Aside from the general principle that lawyers may provide limited representation,21 the MRPC does not explicitly address the ghostwriting issue. In Informal Ethics Opinion 1414 (1978), the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility considered a case of a lawyer who drafted a pro se litigant’s pleadings and memoranda, sat in on his client’s trial, and provided him advice, all without entering a formal appearance.22 The committee found that a lawyer who gives advice to or drafts a pleading for a client does not violate any of the Canons of Ethics under the former ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility. If, however, a lawyer provides additional legal services, the propriety of his conduct will depend upon the facts and the extent of the lawyer’s participation on behalf of a litigant who appears to the court and other counsel as not having representation. In other words, if a lawyer engages in “extensive and undisclosed participation . . . that permits the litigant to falsely appear as lacking professional assistance,” then the lawyer violates the duty of candor to the tribunal.23 Soon after Opinion 1414 was issued, the positions of state courts and ethics bodies fell into three categories: (1) those requiring disclosure of the fact that “extensive” or “substantial” assistance beyond drafting of pleadings was being received (the ABA approach); (2) those finding that the act of ghostwriting a pleading and little more constitutes per se extensive or substantial assistance and requires disclosure of the identity of the ghostwriter (or disclosure that such assistance was received); and (3) those finding that attorneys entering into limited services agreements are bound by all professional responsibility rules, but that no disclosure of ghostwriters’ identities was required.24

In its 2007 Formal Ethics Opinion 07-446 (Opinion 07-446), the ABA Standing Committee reversed itself, finding no unethical conduct on the part of lawyers performing ghostwriting services.25 The committee decided: “A lawyer may provide legal assistance to litigants appearing before tribunals ‘pro se’ and help them prepare written submissions without disclosing or ensuring the disclosure of the nature or extent of such assistance.”26 The committee found that “the fact that a litigant submitting papers to a tribunal on a pro se basis has received legal assistance behind the scenes is not material to the merits of the litigation”;27 “permitting a litigant to file papers that have been prepared with the assistance of counsel without disclosing the nature and extent of such assistance will not secure unwarranted ‘special treatment’ for that litigant or otherwise unfairly prejudice other parties to the proceeding. . . . [I] f the undisclosed lawyer has provided effective assistance, the fact that a lawyer was involved will be evident to the tribunal. If the assistance has been ineffective, the pro se litigant will not have secured an unfair advantage”;28 there is no violation of the prohibition upon dishonesty under MRPC 8.4(c) because “[t]he lawyer is making no statement at all to the forum regarding the nature or scope of the representation, and indeed, may be obliged under Rules 1.210 and 1.611 not to reveal the fact of the representation. Absent an affirmative statement by the client, which can be attributed to the lawyer, that the documents were prepared without legal assistance, the lawyer has not been dishonest within the meaning of Rule 8.4(c)”;29 and, for the same reason, “we reject the contention that a lawyer who does not appear in the action circumvents court rules requiring the assumption of responsibility for their pleadings. Such rules apply only if a lawyer signs the pleading and thereby makes an affirmative statement to the tribunal concerning the matter. Where a pro se litigant is assisted, no such duty is assumed.”30

A growing number of states’ legal ethics committees now agree with the ABA position. They reversed their previous opposition to the practice based on the 1978 Opinion 1414, and now hold that ghostwriting is permissible, with some variation in ghostwriter identity disclosure requirements. But the overwhelming number of federal courts that have expressed an opinion on the subject, with one exception,31 persist in their view that limited representation and ghostwriting violate various state ethics rules (as there are no federal ethics rules for lawyers), even in a state where local rules permit ghostwriting. Colorado, for example, is a state that permits limited representation and disclosed ghostwriting, but federal courts there prohibit these practices.32

One critique of Opinion 07-446 (in an ABA publication, no less), stating that the decision is “seriously flawed,” essentially rehashes all the arguments specifically rejected by the ethics committee.33 This critique relies exclusively on the federal anti-ghostwriting case law. It raises the candor-to-the-tribunal issue, disregarding the fact this ethical duty expressly applies only to “advocates” before the court.34 The authors raise potential Rule 11 concerns, disregarding the fact that courts have the power to hail into court persons or firms that promote the litigation but do not sign their name to pleadings.35 They argue that ghostwriting could be material to litigation because “a lawyer may craft claims or spot defenses that the pro se litigant would not, or [would not] be able to, [and] craft arguments to defeat summary judgment that a pro se litigant would never be able to make”36 — as if that were so bad. Lastly, they argue that ghostwriting has the potential to give ghostwriting lawyers “a free pass to defame or insult courts,”37 in violation of the ethical prohibition against challenging the integrity of the judiciary, surely a speculative stretch, and not sufficient to delegitimize ghostwriting generally.

Another commentator said that the opinion contained “circular reasoning,” and that it “appears to be an attempt to ease the burden on judges and to encourage attorneys to help pro se litigants.”38 One wonders why that would be an improper motivation underlying the opinion. Also skeptical of the practice are the authors of the ABA/BNA Lawyers’ Manual on Professional Conduct, who continue to caution that “[l]awyers who help a pro se litigant by ‘ghostwriting’ a pleading or other court document without revealing their role in creating the document are arguably circumventing their Rule 11 obligation to certify that the pleadings have merit.”39 And insurance defense lawyers are now getting advice regarding “practical strategies that you can employ against pro se litigants assisted by ghostwriting attorneys to achieve the best possible results for your client.”40

Others, however, welcome Opinion 07-446. One attorney, commenting on the undue advantage argument rejected by the committee, stated: “Treating pleadings more leniently does not make it more likely that a pro se litigant will win. . . . It simply makes it more likely that the pro se litigant’s case will be heard on the merits.”41 Even in the habeas corpus petition-drafting context, the new rule also has positive implications:

[F]or those who do wish to practice without making an appearance for even a portion of a case, the ethical freedom to decline to disclose any amount of ghosting is attractive. This is particularly true because the ghost lawyer has no guarantee that the client will follow the game plan as created and designed by the lawyer. . . . This approach affords more options to clients who either cannot afford a lawyer in an ancillary criminal proceeding or do not want to turn their case over completely to a lawyer.42

Opinion 07-446 did not authorize ghostwriting as such, since limited representation is expressly permitted under MRPC 1.2(c). The critical issue is disclosure of the ghostwriter’s identity. We will now examine the variation in state rules governing this issue.

State Rules Governing Ghostwriter Disclosure

Despite criticisms leveled at Opinion 07-446, by 2010, at least a dozen states had modified their procedural rules or ethics decisions to align with the ABA’s position.43 As commentators have noted, “The trend in the cases is in favor of allowing ghost written legal papers.”44 Table 1 (at right) presents an overview of the four major types of current state rules (including both civil pleading/ signature rules and ethics committee opinions) governing disclosure of a ghostwriter’s identity.

Table 1 includes the ABA’s present position and that of D.C., but no category notation appears for the ten states that have no rule on any aspect of ghostwriting. The table shows 18 states (including D.C.) that explicitly permit nondisclosure of the ghostwriter’s identity. Nine states, however, require full disclosure. The states in between those extremes appear in the last two columns and are almost equally divided. Seven states require disclosure when the extent of the ghostwriting — or, for that matter, any form of limited-scope representation — is “substantial” or “extensive” (following the superseded 1978 ABA Informal Ethics Opinion 1414). Nine other states require the fact of assistance be disclosed but not the identity of the ghostwriter; such a disclosure might read, for example, “Prepared by a lawyer licensed in State X.”

The question of ghostwriter identity and other ethical issues relating to ghostwriting continue to be hotly debated in bench and bar meetings and in continuing legal and judicial education programs. Lawyers in states that have a single rule on the subject are lucky to have some guidance. Those in the ten states with no state law or ethical guidance whatsoever only have a multitude of anti-ghostwriting federal opinions to go by. Lawyers in other jurisdictions, like New York and West Virginia, have multiple rules on the subject from different ethics bodies. So, confusion reigns from the lawyers’ perspective, which naturally has a chilling effect on their willingness to ghostwrite. Many individual judges, in addition to lacking guidance, have their own predilections about ghostwriting ethics. Some federal courts have raised state ethics rule violations over ghostwriting practices (or limited representation, generally), even when state law allows these practices.45

Implications for the Right of Access to Courts

At present, federal and many state courts and ethics committees have diametrically opposed views of the propriety of ghostwriting. Moreover, it is not unreasonable to assume that between and within the federal and state judiciary there is also a divergence of opinion between judges who do not permit ghostwriting and judges who overlook ghostwriting (or deny sanctions motions) because there is no authoritative court decision on the matter, because those authorities that do exist are in conflict, or because no specific harm is shown. The authors of a recent book on the subject of ghostwriting in various professions and contexts accurately note: “The weight of case law on this [anti-ghostwriting] side of the issue may be attributable to the strength of sentiment against pro se ghostwriting, for judges who accept the practice may have no reason to issue opinions in support.”46 This lack of uniformity of justice has implications not only for the right of access to courts, but the right to a fair process and equal justice after accessing the court.

This disuniformity constitutes both a real barrier to justice and unequal justice. In fact, a strong argument can be made that these differences between the federal and state courts within a given state constitute a denial of equal protection. One can envision two pro se plaintiffs with a similar case, say, a personal injury matter. One files his complaint in federal court (invoking diversity jurisdiction because the defendant is from out of state), and the other files in state court. The federal plaintiff would be prohibited from ghostwriting assistance, while the state court plaintiff would be able to benefit from it. Which claimant would go further in the litigation and thereby secure access to justice? It goes without saying that the pro se plaintiff in state court would fare much better. Ghostwriting may not, of course, ensure victory, which is based on the facts and the law of the individual case, but it gives the pro se plaintiff a fighting chance at justice. The federal court plaintiff would probably not get past the dispositive motions stage without a ghostwriter’s assistance. He or she would therefore have a potential due process (which includes equal protection)47 claim against the federal court. Moreover, upon a possible appeal, the record in the federal plaintiff’s case would be far less complete than that in an appeal to the state appellate court. The state court appeal would be based on a fuller record, include more issues, and might be more detailed and comprehensible. The issues in the federal court appeal might not even be reached due to the ghostwriting prohibition; thus, similarly-situated pro se plaintiffs’ cases would potentially have different results.

Analysis of Ghostwriting Opinions

There is no way of knowing the extent of undisclosed ghostwriting, but we do have 179 federal and state court reported and unreported opinions to date on the subject for analysis.48 In a previous study, I noted that no specific harm or prejudice from ghostwriting, other than a generalized allegation of undue advantage, was found in the 96 cases studied there.49 The research reported here was conducted to further our understanding of ghostwriting, generally, and ghostwriter identity-disclosure requirements, in particular. The disclosure requirements are unquestionably one of the most pressing issues surrounding this activity. This study examined the case law in order to answer the following questions:

1. How frequently have courts addressed ghostwriting in published opinions?

2. What courts have issued ghostwriting opinions?

3. What are these courts’ views of ghostwriting?

4. Who complains about ghostwriting?

5. Who are the recipients of ghostwriting?

6. Who are the ghostwriters?

7. What is being ghostwritten?

8. To what extent have courts entered sanctions against ghostwriters?

The frequency of ghostwriting opinions has increased since the late 1990s, as has the frequency of pro se litigation. It is likely that the increase in pro se representation has contributed to the frequency of ghostwriting cases although the prevalence of ghostwriting itself can’t be measured accurately.

Courts Issuing Ghostwriting Opinions

In Table 3, we see that it is the U.S. District Courts that have issued the overwhelming number of opinions on the subject (67 percent). Following the district courts are bankruptcy (12 percent) and circuit courts of appeal (8 percent). The fewest opinions have been issued by state supreme, appellate, and trial courts (collectively, 12 percent).

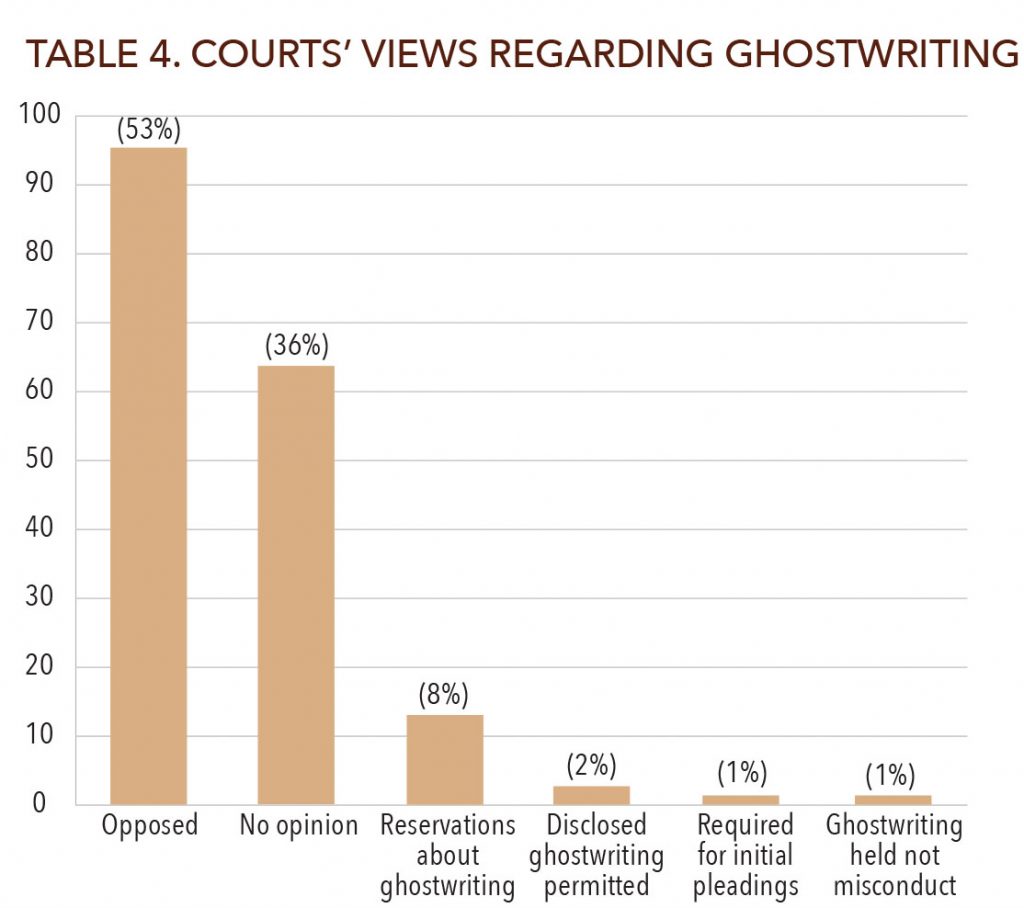

Courts’ Views Regarding Ghostwriting

The largest number of court opinions evidence a judicial opposition to ghostwriting (53 percent) as shown in Table 4. A sizeable proportion (36 percent), however, discuss the subject because it is raised by one of the parties (or the court), but do not express an opinion on it. For example, the court may note that the complaint about a ghostwritten pleading is not substantiated, and, even if it were, it is irrelevant to the case50 or “at best tangentially related to the substance of [the] litigation,”51 or the court may discuss ghostwriting in the context of a question about attorneys’ fees.52 A smaller proportion of courts (8 percent) indicate that they have reservations about ghostwriting. The lowest proportion of cases (4 percent) reflect a judicial opinion that ghostwriting is permitted if disclosed, expressly permit ghostwriting for initial pleadings so long as it is disclosed, or have held that ghostwriting does not constitute misconduct.

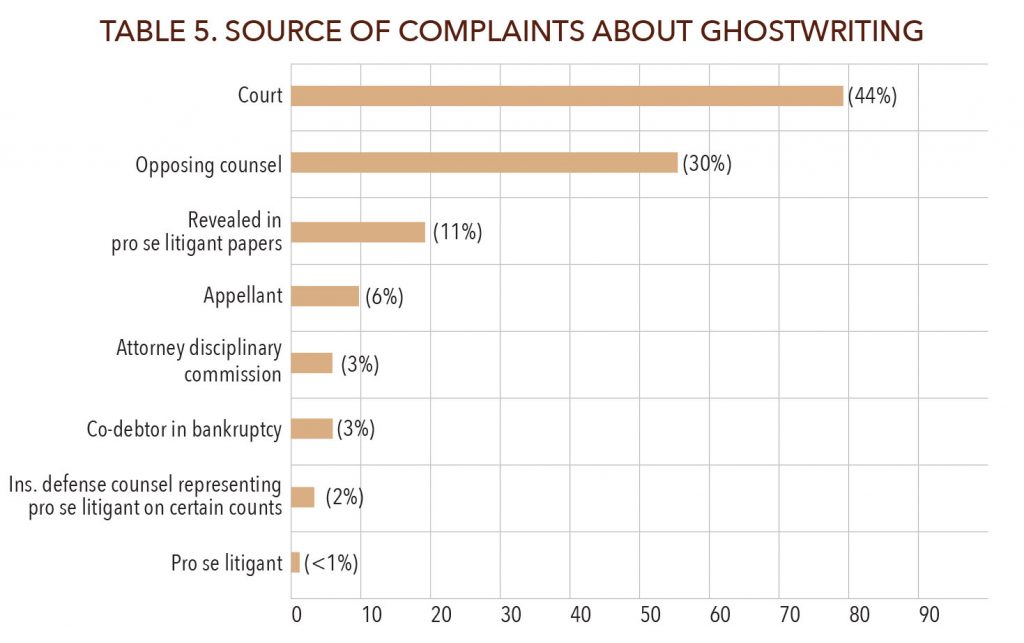

Source of Complaints About Ghostwriting

Table 5 shows that courts (44 percent) and opposing counsel (30 percent) are the primary sources of complaints about ghostwriting. Pro se litigants sometimes expressly reveal ghostwriting in their own pleadings (11 percent). Less often the source of the ghostwriting complaint is an adverse party to an appeal (6 percent), a co-debtor in bankruptcy (3 percent), an attorney disciplinary commission (3 percent), insurance defense counsel (2 percent), or, on rare occasion, a pro se adversary of the pro se litigant receiving ghostwriting assistance (one case).

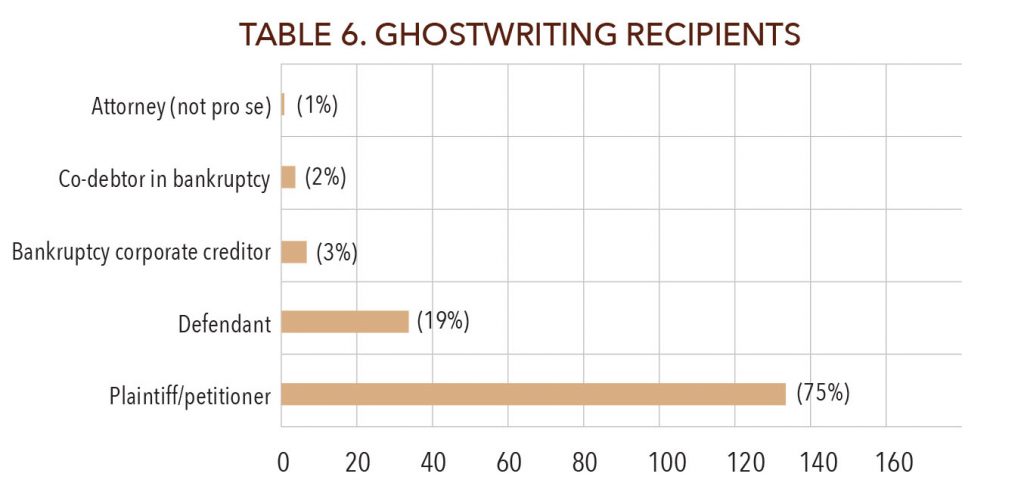

Ghostwriting Recipients

Table 6 shows that the bulk of beneficiaries of ghostwriting are plaintiffs or petitioners (75 percent). Pro se litigants are not, however, always plaintiffs or petitioners. Pro se defendants are in fact the second largest group of ghostwriting recipients (19 percent). Less often, ghostwriting recipients are bankruptcy corporate creditor (not pro se) or co-debtors (5 percent).

Who are the Ghostwriters?

Table 7 shows that licensed attorneys comprise the largest group (67 percent) of ghostwriters.53 Only 12 percent of the ghostwriters turn out to be unlicensed (i.e., disbarred or out-of-state) or suspended attorneys. Occasionally, the court fails to identify the ghostwriter (5 percent), or the ghostwriter is a nonlawyer, a jailhouse lawyer, a paralegal, or even an “offshore company” providing ghostwriting services (collectively 11 percent). There are some cases where the pro se litigant denies the ghostwriting accusation and insists the writings are his or her own (6 percent).

What is Being Ghostwritten?

Not unexpectedly, Table 8 shows that ghostwriting primarily takes the form of drafting, or responding to, dispositive motions (30 percent) and drafting of complaints or amended complaints (27 percent). Ghostwriters also assist in drafting other pleadings (13 percent). Bankruptcy assistance, by way of preparation of schedules of assets and liabilities and assistance with adversary proceedings, is also a common form of ghostwriting (10 percent). Fewer examples of ghostwriting appear in cases involving appellate briefs (5 percent), habeas petitions (5 percent), and a variety of other litigation and discovery documents (collectively 5 percent). In some cases, the nature of the ghostwritten item is unspecified (4 percent), being generically referred to as legal papers.

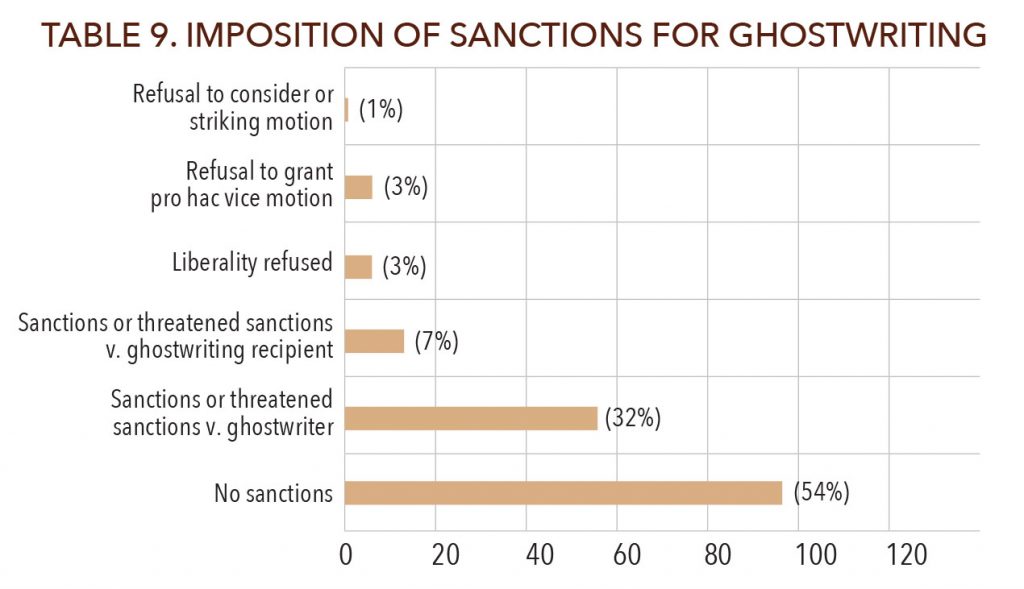

Imposition of Sanctions

Table 9 shows that a bare majority (54 percent) of judges do not sanction the ghostwriter or the ghostwriting beneficiary. A fair number (32 percent), however, do either sanction or threaten sanctions such as reprimands, reference to state ethical bodies, and fines against the ghostwriter. To a far lesser extent, courts sanction or threaten sanctions against the ghostwriting recipient (7 percent). In the fewest number of cases, courts have treated the ghostwriting recipient’s pleading without the liberality to which pro se litigants are entitled (3 percent), or have refused to grant the ghostwriter’s motion to appear pro hac vice (3 percent). In only one case did the court refused to consider or grant a motion (1 percent).

Need for Reform

Relevant to the ghostwriting controversy are lawyers’ ethical obligations described in the MRPC Preamble: “A lawyer, as a member of the legal profession, is a representative of clients, an officer of the legal system and a public citizen having special responsibility for the quality of justice.”54 As a public citizen, a lawyer “should seek improvement of the law and access to the legal system, the administration of justice and the quality of service rendered by the legal profession.”55 “All lawyers should devote professional time and resources and use civic influence to ensure equal access to our system of justice for all those who because of economic or social barriers cannot afford or secure adequate legal counsel.”56 And lawyers also have an ethical duty to “provide legal services to those unable to pay.”57 These points all support the current ABA rule and justify ghostwriting as a means of improving pro se litigants’ access to courts.

The conflicting federal and state positions, however, point to the need for clarification and uniformity regarding ghostwriting and the disclosure of the ghostwriter’s identity. It is time for the federal and state judiciaries and the legal profession to adopt uniform rules governing ghostwriting. Uniform rules will help eliminate conflicting rules among federal courts, state ethics committees (or between the same state’s ethics committees), and individual judges, and such rules can enhance access to justice. One approach would be to request the Uniform Law Commission to develop a proposed uniform statute or rule on the subject. In order for that body to accept an issue for harmonization, “[t]he subject of the act must be such that uniformity of law among states will produce significant benefits to the public through improvements in the law,”58 which certainly applies in the ghostwriting context. Or, perhaps a joint state-federal task force composed of members of state and federal judiciaries, such as representatives from the Conference of Chief Justices and the Judicial Conference of the U.S. Courts, as well as bar representatives could be empaneled to address the ghostwriting issue.

However a uniform rule is proposed, it should, in my view, contain the following elements:

1. The rule should recognize the pro se litigant’s general right of confidentiality regarding the fact and identity of legal counsel, subject to disclosure for cause (e.g., filing a scurrilous pleading) or when an attorney personally appears to advocate on behalf of the client.

2. The rule should establish a preponderance standard on any party complaining of a pro se litigant’s undue advantage from ghostwriting, requiring a showing of specific harm from the practice. Such finding should be a condition for the entry of any order relating to the identity of the ghostwriter, the services he or she provides, termination of preferences in treatment the pro se litigant would otherwise receive, or any other relevant issue.

3. The rule should contain an explicit provision stating that a pro se litigant who receives limited legal (ghostwriting) assistance is still entitled to be treated as a pro se litigant for all purposes not in the control of his attorney under a limited representation.59

The ghostwriting controversy must be resolved — and sooner rather than later. A discussion about uniformity is necessary to develop a consensus on the potential benefits and harms, if any, of the practice, to identify best practices for its management, and to provide clear guidance for lawyers willing to provide ghostwriting services.60 I agree with the admonition that, “[i]f legal ghostwriting ceased to exist, indigent clients might find themselves completely without legal assistance, which would surely have a negative impact on them and their families.”61 The time has come for federal courts and states to resolve the impasse, to harmonize conflicting ghostwriting rules, and to legitimize ghostwriting as a way to expand pro se litigants’ access to justice.

May We Suggest: Typography for Judges

Footnotes:

- Forrest S. Mosten, Unbundling of Legal Services and the Family Lawyer, 28 Fam. L.Q. 421 (1994). “Unbundling can be either vertical or horizontal. Vertical unbundling breaks up the lawyer’s role into a number of limited legal services, empowering the client to select only those needed. Horizontal unbundling limits the lawyer’s involvement to a single issue or court process.” Forrest S. Mosten, Unbundled Legal Services Today — and Predictions for the Future, 35 Fam. Adv. 14 (2012). Ghostwriting is classified as an example of vertical unbundling.

- Kan. Sup. Ct. R. 115A (governing “limited representation”); Colorado RPC 121, § 1-1(5).

- Forrest S. Mosten, Unbundling Legal Services in 2014: Recommendations for the Courts, 53 Judges’ J. 10, 10 (2014).

- FED. R. CIV. P. 11 requires, inter alia, that “[e]very pleading, written motion, and other paper must be signed by at least one attorney of record in the attorney’s name — or by a party personally if the party is unrepresented.”

- Klein v. Spear, Leeds & Kellogg, 309 F. Supp. 341 (S.D.N.Y. 1970).

- Id. at 342–43. The court reluctantly denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss several counts of the pro se complaint, adding its regret that, “having blunted [the pro se plaintiff’s] spear, we cannot also impale him upon it.” Id. at 344.

- Klein v. H.N. Whitney, Goadby & Co., 341 F. Supp. 699, 702 (S.D.N.Y. 1971) (citing Spear, Leeds & Kellogg, 309 F. Supp. 341 (S.D.N.Y. 1970)).

- Ellis v. Maine, 448 F.2d 1325, 1328 (1st Cir. 1971) (“[The ghostwriter] thus escape[s] the obligation imposed on members of the bar, typified by F.R.Civ.P. 11, . . . of representing to the court that there is good ground to support the assertions made. We cannot approve of such a practice. If a brief is prepared in any substantial part by a member of the bar, it must be signed by him. We reserve the right, where a brief gives occasion to believe that the petitioner has had legal assistance, to require such signature, if such, indeed, is the fact.”).

- Johnson v. Bd. of Cty. Comm’rs, 868 F. Supp. 1226, 1231 (D. Colo. 1994), aff’d, 85 F.3d 489 (10th Cir. 1996), cert. denied sub nom., Greer v. Kane, 519 U.S. 1042 (1996); see also, Laremont-Lopez v. Se. Tidewater Opportunity Ctr., 968 F. Supp. 1075, 1078 (E.D. Va. 1997) (“The situation places the opposing party at an unfair disadvantage, interferes with the efficient administration of justice, and constitutes a misrepresentation to the Court.”).

- Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct r. 3.3(a) (1) (Am. Bar Ass’n 2016) (“(a) A lawyer shall not knowingly: (1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer; . . . .”).

- See, e.g., Duran v. Carris, 238 F.3d 1268, 1272–73 (10th Cir. 2001) (finding that ghostwriting constitutes a “misrepresentation to this court”).

- Jona Goldschmidt, In Defense of Ghostwriting, 29 Fordham Urban L.J. 1145 (2002).

- Id. at 1169.

- See Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 advisory committee’s note to the 1983 amendment (“The sanction should be imposed on the persons — whether attorneys, law firms, or parties — who have violated the rule or who may be determined to be responsible for the violation. . . . When appropriate, the court can make an additional inquiry in order to determine whether the sanction should be imposed on such persons, firms, or parties either in addition to or, in unusual circumstances, instead of the person actually making the presentation to the court.” (emphasis added)).

- Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519, 520 (1972) (holding that pro se complaints must be liberally construed).

- Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45–46 (1957), abrogated by Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007).

- Pegram v. Herdich, 530 U.S. 211, 230 n.10 (2000).

- Goldschmidt, supra note 12, at 1157.

- Id. (footnotes omitted).

- Id. at 1158.

- Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct r. 1.2(c) (Am. Bar Ass’n 2016); Restatement (Third) of The Law Governing Lawyers §§ 19(1)(a)–(b) (noting that lawyer may agree to limit a duty that he or she would otherwise owe to a client if the client is adequately informed and consents, and the terms of the limitation are reasonable).

- ABA Comm’n on Ethics & Prof’l Responsibility, Informal Op. 1414 (1978).

- Id. Opinion 1414 is noteworthy for having cited to the aforementioned Klein (I), Klein (II), and Ellis decisions, none of which cited any specific violation of an ethical duty or rule of professional responsibility.

- Goldschmidt, supra note 12, at 1166.

- ABA Comm’n on Ethics & Prof’l Responsibility, Formal Op. 07-446 (2007).

- Id. at 1.

- Id. at 2.

- Id. at 3.

- Id. at 3–4.

- Id. at 4. Here, the committee should have cited to the aforementioned 1993 Advisory Committee Notes, which clarify the court’s power to enforce Rule 11 against those who promote, but do not sign, frivolous pleadings.

- In re Fengling Liu, 664 F.3d 367, 371 (2d Cir. 2011) (relying on a New York County Lawyers’ Association ethics opinion and the ABA Formal Ethics Opinion 07-446 to hold that ghostwriting lawyer should not be sanctioned, that, where disclosure of ghostwriter assistance is required by rule, order, or circumstances, it may be stated in a general way, and that there is no dishonesty “as long as the client does not make an affirmative representation, attributable to the attorney, that the pleadings were prepared without an attorney’s assistance”).

- Compare, e.g., Colorado Bar Ass’n, Ethics Op. 101 (1998) (updated May 21, 2016) (permitting unbundled legal services and ghostwriting, but requiring lawyer ghostwriters to state their name, address, telephone number and registration number on pleadings they draft), with U.S. Dist. Ct. Rules LAttyR 2 (adopting Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct for the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, but stating that provisions of Colo. RPC 1.2(c) [limiting scope of representation] “are excluded”).

- Douglas R. Richmond, Brian S. Faughnan & Michael L. Matula, Professional Responsibility in Litigation 482, 484 (2011).

- The candor-to-the-tribunal rule prohibits the following acts: making false statements to the court; failing to disclose a material fact to a tribunal when necessary to avoid assisting a client commit a crime or fraud; failing to disclose controlling, adverse legal authority to the court; and offering evidence known to be false. These duties “continue to the conclusion of the proceeding.” The rule’s commentary refers to the “advocate’s task,” the “advocate’s duty of candor to the tribunal,” and the advocate’s responsibility for pleadings and documents, all of which indicate that it is directed to attorneys appearing in court as “advocates.” See Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct r. 3.3(a)(1)–(3) & (b) (Am. Bar Ass’n 2016).

- See Lockary v. Kayfetz, 974 F.2d 1166 (9th Cir. 1992) (noting that the court may sanction, under its inherent powers, a nonprofit legal corporation that controlled and paid for litigation).

- Richmond et al., supra note 33, at 484.

- Id.

- Lynn A. Epstein, With a Little Help from My Friends: The Attorney’s Role in Assisting Pro Se Litigants in Negotiations, 13 T.M. Cooley J. Prac. & Clinical L. 11, 17 (2010).

- Am. Bar Ass’n, Ctr. for Prof’l Responsibility, ABA/BNA Lawyers’ Manual on Professional Conduct, 61:101 (updated 2008).

- Peter M. Cummins, The Cat-O’-Ten-Tails — Pro Se Litigants Assisted by Ghostwriting Counsel, 53 For the Def. 40, 45 (Apr. 2011).

- Richard Acello, Seeing Ghosts: Lawyer-Drafted Pleadings for Pro Se Litigants are Scaring Fewer Courts, 96 A.B.A. J. 24, 25 (2010).

- J.Vincent Apple II, Ghostwriter: A New Legal Superhero?, 23 Crim. Just. 44, 45 (2008); see also Toni L. Mincielli, Let Ghosts Be Ghosts, 88 St. John’s L. Rev. 763 (2014 (advocating ghostwriting for immigrants facing deportation).

- Acello, supra note 41, at 25.

- Ronald D. Rotunda & John S. Dzienkowskia, Legal Ethics, in Law. Deskbk. Prof. Resp. § 6.5-4 (2017–2018 ed.).

- See, e.g., In re Merriam, 250 B.R. 724 (D. Colo. 2000) (noting that the limited representation and disclosed ghostwriting allowed by state legal ethics rules do not negate ethical obligation of candor to the court, and obligating ghostwriter lawyer to attend creditors’ meeting); Kear v. Kohl’s Dept. Stores, Inc., 2012 WL 5417321, *1 (D. Kan. 2012) (finding that state rule permitting unbundling does not negate court’s concern regarding “ethical requirement of candor to the tribunal, the danger of circumvention of the requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 11, and the effect of applying more generous interpretive standards to apparent, but not actual, pro se pleadings”).

- John C. Knapp & Azalea M. Hulbert, Ghostwriting and the Ethics of Authenticity 72–73 (2017). The authors provide a chapter reviewing the issues of legal and judicial ghostwriting. Unfortunately, it leaves out the 2007 ABA Formal Ethics Opinion 07-446, which changed the landscape of ghostwriting ethics.

- Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 498–99 (1954) (discrimination by a federal actor or entity may nevertheless be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process).

- Both published and unpublished opinions were found and included in the analysis. Excluded were cases involving attorney ghostwriting of experts’ reports, and judicial ghostwriting (e.g., where judge makes ex parte request of counsel to draft court’s order).

- Jona Goldschmidt, An Analysis of Ghostwriting Decisions: Still Searching for the Elusive Harm, 95 Judicature 78, 85 (2011). The same results were obtained in this study of 179 opinions.

- Porcaro v. O’Rourke, 2008 WL 4456752 (Mass. App. Div. Sept. 25, 2008).

- ADI Motorsports v. Hubman, 2006 WL 3421819 (W.D. Va. Oct. 20, 2006).

- Gilbert v. Wisdom, 2007 WL 20843336 (Cal. Ct. App. July 23, 2007).

- A coding assumption was made that the ghostwriter was a licensed attorney if the court referred to him or her as a lawyer or attorney, unless there were facts indicating the ghostwriter was suspended, disbarred, or from out of state.

- Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct preamble, ¶ 1 (Am. Bar Ass’n 2016 (emphasis added).

- Id. ¶ 6 (emphasis added).

- Id. (emphasis added).

- Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct r. 6.1 (Am. Bar Ass’n 2016).

- Uniform Law Commission, Statement Of Policy Establishing Criteria And Procedures For Designation And Consideration Of Uniform And Model Acts, § 1(c), http://www.uniformlaws.org/Narrative.aspx?title=Criteria%20for%20New%20Projects. The Statement notes that if the subject matter is within the concurrent jurisdiction of the federal and state governments and Congress has not preempted the field, it may be appropriate for action by the states and, hence, by the ULC. Id. § 1(a).

- Goldschmidt, supra note 12, at 1207–08. One anonymous reviewer suggested that the ABA modify its Ethics Opinion 07-446 by requiring disclosure of the ghostwriter’s identity, which would return it to its 1978 position. This approach in my view would sow further confusion, especially among states that have already changed their views consistent with Opinion 07-446.

- Knapp & Hulbert, supra note 46, at 76.

- Id. at 78.