A Statutory Oddity

Vol. 105 No. 3 (2021) | Leaving Afghanistan | Download PDF Version of Article

The Different and Sometimes Convoluted Ways that Congress Granted Circuit Court Trial Jurisdiction to the 19th-Century Federal District Courts

Doing research for a book on the history of the federal courts of appeals,1 I stumbled serendipitously2 upon an oddity of the early district courts and the pre-1911 circuit courts (not the numbered appellate circuits we now have). Apparently no one else has noticed this oddity, not even several scholars of the federal judiciary in the 19th century whom I have consulted.3 Their unawareness of this obscure bit of federal court history suggested to me that an article on the matter might be of interest to readers of Judicature.

Some Background

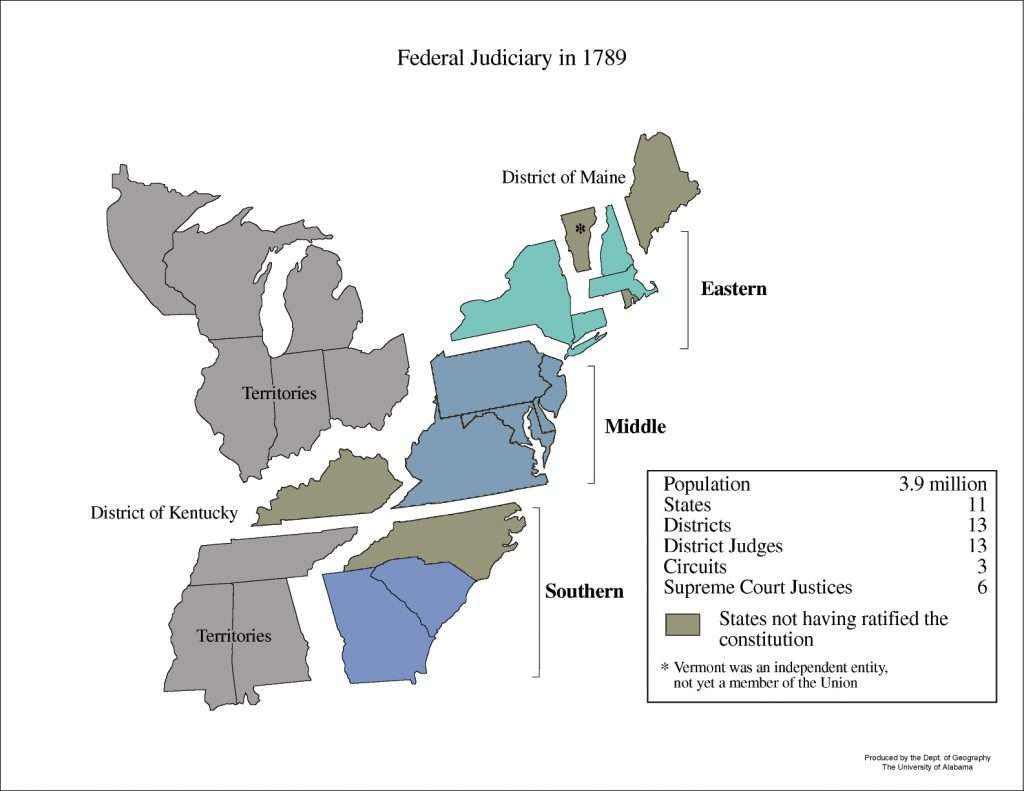

Congress created 13 judicial districts on Sept. 24, 1789, in the First Judiciary Act (1789 Act).4 At that time, 11 of the original 13 colonies had become states, all except North Carolina and Rhode Island. Nine judicial districts consisted of the entirety of the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina; one district was part of the state of Massachusetts; and one district was part of the state of Virginia. These 11 districts were grouped into the Eastern, Middle, and Southern Circuits.5 Two districts were not grouped into circuits: the “Maine District,” which was the remaining part of Massachusetts,6 and the “Kentucky District,” which was the remaining part of Virginia.7

The 1789 Act established a district court in each of these 13 original districts “to consist of” a district judge, who annually held four sessions.8 District courts were established in North Carolina and Rhode Island in 1790,9 shortly after these states had ratified the Constitution.

The 1789 Act also established a circuit court in 11 of the original districts,10 but explicitly not in the Kentucky District or the Maine District.11 The lack of a circuit court in the Kentucky District would turn out to have special significance for the subject of this article.

Circuit courts were established in North Carolina and Rhode Island in 1790.12 A circuit court, which held two sessions each year,13 was “to consist of” the local district judge and two Supreme Court justices,14 thereby imposing circuit-riding obligations on the justices. These obligations were briefly ended by enactment of the infamous Midnight Judges Act of 1801 (1801 Act),15 but the repeal of that act in 1802 “revived” all acts repealed by the 1801 Act and re-instated circuit-riding.16 A second statute enacted in 1802 eased the justices’ obligations by reducing the composition of each circuit court to one Supreme Court justice (the one residing in the then-existing six circuits) and the local district court judge17 In 1869, Congress further eased the burden of circuit-riding by authorizing the President to appoint a circuit judge in each of the nine then-existing circuits, and by providing that a circuit court could consist of the Supreme Court justice allotted to the circuit,18 or the circuit judge for the circuit, or the district judge of the district each sitting alone, or the Supreme Court justice and the circuit judge, or either of them and the district judge, sitting together.19

The district courts had limited civil and criminal jurisdiction. Civil jurisdiction, exclusive of the state courts, extended to civil causes of admiralty or maritime jurisdiction, including seizures of vessels of ten or more “tons burthen,”20 and, concurrent with the state courts and the circuit courts, extended to suits brought by the United States where the matter in controversy was up to $100, all suits against consuls and vice-consuls, and “causes where an alien sues for tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.”21 The district courts in the Districts of Kentucky and Maine also had removal jurisdiction from state courts, invoked by a defendant for suits brought by an alien or by a citizen of one state against a citizen of another state and the matter in controversy exceeded $500.22 Criminal jurisdiction of the district courts, exclusive of the state courts, extended to all federal crimes committed in the district or on the high seas, with a maximum punishment of whipping not exceeding 30 stripes, a fine not exceeding $100, or imprisonment not exceeding six months.23

The circuit courts during that time were very different from today’s federal appellate “circuit courts.” They had both trial and appellate jurisdiction. Their civil trial jurisdiction, concurrent with the state courts, extended to civil cases where the United States was a plaintiff and the matter in dispute exceeded $500, the plaintiff was an alien, or the parties were citizens of different states.24 Their criminal trial jurisdiction, exclusive of the state courts, extended to all federal crimes and was concurrent with the criminal jurisdiction of the district courts.25 The circuit courts also had removal jurisdiction from state courts, invoked by a defendant for suits brought by an alien or by a citizen of one state against a citizen of another state and the matter in controversy exceeded $500.26 Although Justice Joseph Story characterized removal jurisdiction as appellate jurisdiction,27 reference in this article to “trial jurisdiction” of a circuit court will include removal jurisdiction because almost all removed cases were removed before trial.

The appellate jurisdiction of the circuit courts extended to final decrees and judgments in civil actions in a district court where the matter in controversy exceeded $50,28 and to final decrees in a district court in causes of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction where the matter in controversy exceeded $300.29 Because the Districts of Kentucky and Maine did not have a circuit court in 1789, appeals from the district court for the District of Kentucky were taken to the Supreme Court,30 and appeals from the district court for the District of Maine were taken to the circuit court for the District of Massachusetts.31

In 1891, Congress ended the appellate jurisdiction of the old circuit courts and created the modern courts of appeals in each circuit (today’s “circuit courts”) with jurisdiction to review all judgments of the district courts.32 In 1911, Congress abolished the old circuit courts.33

The Oddity Begins

Against that background, the 1789 Act laid the groundwork for the oddity described in this article by giving the district courts for the Districts of Kentucky and Maine the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court in addition to the jurisdiction of a district court.34 These two districts did not then have a circuit court.

Note how simply and directly Congress gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to these two district courts. The Kentucky district court, said section 10 of the 1789 Act, “shall, besides the jurisdiction aforesaid [i.e., district court jurisdiction], have jurisdiction of all other causes, except appeals and writs of errors, hereinafter made cognizable in a circuit court.”35 Section 10 used similar language for the district court for the District of Maine.36

In 1797, Congress for the first time granted the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court to a district court in an odd way. The statute enacted that year (1) created the judicial District of Tennessee, (2) established a district court for that district, and, pertinent to this article, (3) indirectly gave the district judge of that district court the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court by authorizing the Tennessee district court judge to “exercise the same jurisdiction and powers, which by law are given to the judge of the district of Kentucky,” i.e., the trial jurisdiction of both a district court and a circuit court.37 Because the Tennessee district court judge already had district court jurisdiction by being the judge of a district court, the jurisdiction added by giving the Tennessee judge the jurisdiction of “the judge of the district of Kentucky” was the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court.38

Congress used the same indirect way to authorize other district court judges to exercise the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court. In 1803, Congress gave the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court to the judge of the district court for the newly created District of Ohio39 by again giving the Ohio district judges the same trial jurisdiction of the judges of the district court for the District of Kentucky. In 1804, Congress used the same device to give the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court to the judge of district court for the newly created district for the territory of Orleans (the Louisiana Territory).40 In 1805, Congress gave the jurisdiction of the district court of the Kentucky district to the superior courts (trial courts) of the territories of the United States.41 This reference to the jurisdiction of the Kentucky district court is entirely understandable for these superior courts because the territories had no district courts; thus the reference to the Kentucky district court was a convenient way to give the superior courts the trial jurisdiction of both the district and circuit courts.

With circuit courts established in 11 of the original 13 districts ever since 1789, it seems odd that Congress did not directly give the district judges for the Districts of Tennessee, Ohio, and the Orleans Territory the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court, as Congress had done for the district judges in the Districts of Kentucky and Maine.

In fact, from 1814 to 1877, Congress gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to district courts directly, i.e., by giving them such jurisdiction without referring to the jurisdiction of the Kentucky district court, in 15 districts: the Northern District of New York in 1814,42 the Western District of Pennsylvania in 1818,43 the Western District of Virginia in 1819,44 the Middle District of Alabama in 1839,45 the Western District of Tennessee in 1839,46 the District of Texas in 1845,47 the Northern District of Georgia in 1848,48 the Northern and Southern Districts of California in 1850,49 the district court for the District of South Carolina when sitting in Greenville in 1856,50 and the Eastern District of Arkansas at Helena, the Western District of Arkansas, the Northern District of Mississippi, the Western District of South Carolina, and the District of West Virginia in 1877.51

Yet, despite giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to these 15 district courts directly from 1814 to 1877 (17 in all starting from 1789, counting the district courts of Kentucky and Maine), Congress used the indirect (some might say circuitous) way of giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to ten district courts by referencing the Kentucky district court from 1817 to 1846 (12 in all starting from 1803, counting the district courts of Ohio and the Louisiana Territory). This one-step method was used in the Districts of Indiana in 1817,52 Mississippi in 1818,53 Illinois in 1819,54 Alabama in 1820,55 Missouri in 1822,56 Arkansas in 1836,57 Michigan in 1836,58 Florida in 1845,59 Iowa in 1845,60 and Wisconsin in 1846.61

Because the circuit court trial jurisdiction of the Kentucky district judge ended in 1807 with the establishment of a circuit court for the District of Kentucky, Congress could not in the later years give circuit court trial jurisdiction to a district court judge in a new district by giving such judge the Kentucky district judge’s existing jurisdiction. So, when giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to the Mississippi district court judge in 1818, for example, Congress gave the judge the circuit court trial jurisdiction that a Kentucky district court judge had in 1789 “under judicial courts of the United States,’”62 i.e., the 1789 Act. Thus, with the exception of Ohio and the Louisiana Territory (which were both dealt with pre-1807), Congress referred to the jurisdiction that a Kentucky district court judge had in 1789 when giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to the remaining ten district courts noted above.

The Oddity Becomes Convoluted

Between 1812 and 1850, Congress three times gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to district judges in a doubly indirect way by using a two-step method. In 1812, Congress gave the judge of the district court for the District of Louisiana “the same jurisdiction and powers . . . given to the district judge of the territory of Orleans,”63 who had the jurisdiction of a district court judge in the District of Kentucky,64 who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court. In 1858, Congress gave the district judge for the District of Minnesota the jurisdiction of the district judge of the District of Iowa,65 who had the jurisdiction of the district judge of the District of Kentucky,66 who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court. In 1859, Congress similarly gave the district judge of the District of Oregon the jurisdiction of the district judge of the District of Iowa,67 who had the jurisdiction of the district judge of the District of Kentucky, who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court.68

In 1861, the oddity of granting circuit court trial jurisdiction to the district courts reached its zenith when Congress used a triply indirect way to give circuit court trial jurisdiction to a district court by using a three-step method. In that year, Congress gave the district court for the District of Kansas the jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Minnesota,69 which had the jurisdiction of the district judge for the District of Iowa,70 who had the jurisdiction of the district judge of the District of Kentucky,71 who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court.

The Oddity Ends

After 1877, Congress never gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to a district court in a state.72 Instead, as new states were admitted, Congress established a circuit court in the state. This occurred, for example, in 1889 when Montana, North and South Dakota, and Washington were admitted, and a circuit court was established in these states.73 Of course, even before 1877, Congress had established circuit courts in several new states upon their admission,74 and had done so in districts that were a portion of new states.75 Presumably, Congress gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to many district courts, instead of establishing circuit courts in those districts, in order to spare Supreme Court justices circuit-riding assignments to distant districts.

The oddity I have identified is not that Congress gave the district courts in 33 districts the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court from 1789 to 1877.76 That was a sensible way to provide circuit court trial jurisdiction in these districts because they did not then have a circuit court. What was odd, and what has not been previously noticed, is that Congress gave such circuit court trial jurisdiction to district courts in four different ways, three of which were needlessly convoluted. For 17 district courts, Congress directly gave them the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court. But for 12 other district courts, Congress gave that jurisdiction indirectly by giving the district court judge of these district courts the jurisdiction of the district court judge in Kentucky, who had the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court. More surprising, Congress three times gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to a district court judge in a doubly indirect way by giving a district court judge the jurisdiction of a district court judge in another district, who had been given the circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court judge in Kentucky, who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court. And, even more surprisingly, Congress once gave circuit court trial jurisdiction to a district court in a triply indirect way by giving one district court the jurisdiction of another district court, which had been given the jurisdiction of a district court judge in another district, who had been given the circuit court jurisdiction of the district court judge in Kentucky, who had the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court.

Why the Oddity?

Why did Congress use these three convoluted ways when the direct way of simply giving a district court the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court was always available? I do not know. A possible explanation for indirectly giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to district judges in 17 districts by giving them the jurisdiction of the judge of the district court for the District of Kentucky is that a prominent congressman and senator at the time was Henry Clay of Kentucky.77 Perhaps he insisted that many jurisdictional roads should lead through his home state. Or perhaps the references to the district court of Kentucky were the idea of Isham Talbot, a Kentucky Senator who had a lot to say to the Senate about the organization of the early federal courts.78 Or perhaps Congress, for no particular reason, was sometimes following the 1797 statutory precedent of giving circuit court trial jurisdiction via Kentucky to the district judge of the newly created district court for the District of Tennessee, the 1803 precedent of similarly giving such jurisdiction to the district judge of the district court for the District of Ohio, and the 1804 precedent of similarly giving such jurisdiction to the district judge of the district court for the Louisiana Territory.79 Nothing comes to mind why Congress would give circuit court trial jurisdiction to three other district courts in a doubly indirect way and to one other district court in a triply indirect way.

I make no claim that the oddity I have discovered has any significance at all. But it ought to be known after all these years of lying undiscovered.80 And, just possibly, making it known might serve as advice to Congress: When you want to legislate a result, spare us the convolution — say it simply.81

Jon O. Newman is a senior judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

* This article could not have been written without the availability of the Federal Judicial Center’s online Legislative History links to the history of the federal district and circuit courts of every state. I am grateful to Thomas Lee, professor of law at the Fordham Law School, and Russell Wheeler, adjunct professor of law at Washington College of Law, visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, and formerly deputy director of the Federal Judicial Center. Both made several helpful comments after reviewing an early draft.

- Jon O. Newman & Marin K. Levy, Written and Unwritten — The Rules, Practices, and Internal Procedures of the Federal Courts of Appeals (forthcoming).

- “Serendipity” has come to mean any event of good fortune, but I use it in its original meaning of “the faculty or phenomenon of finding valuable or agreeable things not sought for.” Serendipity, Merriam-Webster, merriam-webster.com/dictionary/serendipity. Horace Walpole is said to have coined the word in a letter written in 1754, which mentioned what he called a “silly fairy tale” he had read, “The Three Princes of Serendip.” On a journey from Serendip (the classical Persian name for Ceylon, now Sri Lanka) to seek riches, the three princes unexpectedly come upon a camel merchant who had lost a camel. Using clues told to them by the merchant, the princes are able to describe the camel, which they have never seen. The princes are accused of stealing the camel and brought before the emperor Beramo. When a camel fitting the princes’ description is found, the emperor lavishly rewards their ingenuity and makes the princes his advisors. The story of the lost camel dates back to 1010. The Three Princes of Serendip, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Three_Princes_of_Serendip.

- Professors William R. Casto, Robert W. Gordon, Andrew Kent, John H. Langbein, Thomas H. Lee, Henry P. Monaghan, Edward A. Purcell, Russell Wheeler, and Keith Whittington.

- 1789 Act, § 2, 1 Stat. 73, 73.

- The Eastern Circuit comprised the Districts of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York; the Middle Circuit comprised the Districts of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia; and the Southern Circuit comprised the Districts of Georgia and South Carolina. Id. § 4, 1 Stat. 73, 74–75.

- Id. § 2, 1 Stat. 73.

- Id.

- Id. § 3, 1 Stat. 73, 73–74.

- Act of June 4, 1790, ch. 17, 1st Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 1 Stat. 126 (North Carolina); Act of June 23, 1790, ch. 21, 1st Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 1 Stat. 128 (Rhode Island).

- 1789 Act, § 4, 1 Stat. 73, 74.

- Id.

- Act of June 4, 1790, ch. 17, 1st Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 1 Stat. 126 (North Carolina); Act of June 23, 1790, ch. 21, 1st Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 1 Stat. 128 (Rhode Island).

- 1789 Act § 4, 1 Stat. 73, 74-75.

- Id. § 4, 1 Stat. 73, 74–75.

- Act of Feb. 13, 1801, ch. 4, 6th Cong., 2d Sess., 2 Stat. 89.

- Act of Mar. 8, 1802, ch. 8, 7th Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 2 Stat. 132. This act provided that the repealed acts (both the Feb. 13, 1801, Act and the Mar. 3, 1801, Act) “shall be, and hereby are, after the first day of July next, revived, and in full and complete force and operation, as if the said two acts had never been made.” Act of Mar. 8, 1802, § 3. The circuit-riding obligations of the Supreme Court justices resulted in their presiding at some famous trials, notably the treason trial of Aaron Burr at which Chief Justice John Marshall presided. United States v. Burr, 25 F. Cas. 187 (C.C.D.Va. 1807). The jury acquitted Burr.

- Act of Apr. 29, 1802, ch. 31, 7th Cong., 1st Sess., § 4, 2 Stat. 156, 157.

- Before 1869, as new states were admitted to the Nation, Congress had created new circuits and had added justices to the Supreme Court, allotted to the new circuits. In 1807, Congress created the Seventh Circuit and added one justice to the Supreme Court. Act of Feb. 24, 1807, ch. 16, 9th Cong., 2d Sess., §§ 2, 5, 2 Stat. 420, 421. In 1837, Congress created the Eighth and Ninth Circuits and added two justices to the Supreme Court. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 1, 5 Stat. 176–77.

- Act of Apr. 10, 1869, ch. 21, 41st Cong., 1st Sess. § 2, 16 Stat. 44–45.

- A “ton burthen” is a volumetric measurement of a ship’s cubic capacity for cargo. The American system of measurement from 1789 to 1864 used the formula: a ton burthen = (length x beam x depth) ÷ 95, and measured length from the posts inside the stern and the sternpost and measured breadth from inside the planks.

- 1789 Act, § 9, 1 Stat. 73, 77. The last clause survives to this day as the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) with slightly different wording from the 1789 version. See 28 U.S.C. § 1350. Although in terms only a grant of jurisdiction, the clause, largely dormant for nearly two centuries, achieved significance in 1980 when the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that it permitted a cause of action for a victim of torture against a government official in Paraguay, Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980), and again in Kadic v. Karadzic, 70 F.3d 232 (2d Cir. 1995), when the same court ruled that it authorized suit by victims of war crimes against Slobodan. Karadzic, the Serbian leader of the breakaway state of Srpska, following the collapse of Yugoslavia, id. at 238–45. The Supreme Court later ruled that the ATS was only a grant of jurisdiction, but that the common law “would provide a cause of action for a modest number of international law violations.” Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692, 724 (2004). The significance of the ATS was substantially reduced by the Supreme Court’s later decision in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., which held that the ATS applies only to “conduct [that] took place outside the United States” and claims that “touch and concern the territory of the United States . . . with sufficient force to displace the presumption against extraterritorial application.” 569 U.S. 108, 124–25 (2013).

- 1789 Act, § 12, 1 Stat. 73, 79.

- Id. § 9, 1 Stat. 73, 77.

- Id. § 11, 1 Stat. 73, 78–79.

- Id.

- Id. § 12, 1 Stat. 73, 79.

- Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304, 349 (1814) (“This power of removal . . . is always deemed . . . an exercise of appellate . . . jurisdiction.”).

- 1789 Act, § 22, 1 Stat. 73, 84.

- Id. §§ 21, 22, 1 Stat. 73, 83, 84. Although the 1789 Act provided that the local district judge could be a member of the circuit court, it also provided that “no district judge shall give a vote in any case of appeal or error from his own decision; but may assign the reasons for such his [sic] decision.” Id. § 4, 1 Stat. 75. The 1789 Act did not similarly preclude a Supreme Court justice from “giv[ing] a vote” in a case in which the justice has been a member of a circuit court whose decision the Supreme Court was reviewing, apparently leaving the issue to the justices themselves. Id.

- Id.

- Id. § 10, 1 Stat. 73, 77–78.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1891, ch. 517, 51st Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 26 Stat. 826. When created in 1891, these courts were called circuit courts of appeals, id., but renamed United States Courts of Appeals in 1948. Act of June 25, 1948, ch. 646, 80th Cong., 2d Sess., § 43, 62 Stat. 869, 870.

- Judicial Code of 1911, § 289, 36 Stat. 1087, 1167.

- 1789 Act, § 10, 1 Stat. 73, 77–78. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the Kentucky district court ended in 1807 when a circuit court was established for the District of Kentucky. Act of Feb. 24, 1807, ch. 16, 9th Cong., 2d Sess. § 1, 2 Stat. 420. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the Maine district court ended in 1820 when a circuit court was established for the District of Maine. Act of Mar. 30, 1820, ch. 27, 16th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 554, 554.

- 1789 Act, § 10, 1 Stat. 73, 77–78 (emphases added).

- Id. The wording of the grants of circuit court trial jurisdiction to the district courts for the Districts of Kentucky and Maine differed slightly. For the District of Kentucky, the statute says, “[T]he district court in Kentucky district shall, besides the jurisdiction aforesaid, have jurisdiction of all other causes, except appeals and writs of error, hereinafter made cognizable in a circuit court.” Id., 1 Stat. 77. For the District of Maine, the statute says, “And the district court in Maine district shall, besides the jurisdiction herein before granted, have jurisdiction of all causes, except appeals and writs of error[,] herein made cognizable in a circuit court.” Id., 1 Stat. 78.

- Act of Jan. 31, 1797, ch. 2, 4th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 1 Stat. 496.

- I make this obvious point because one scholar of the early circuit courts, the late Prof. Erwin C. Surrency, maintained that the Kentucky district court “was the first court in which the jurisdiction exercised by district and circuit courts was merged.” Erwin C. Surrency, History of the Federal Courts 352 (1987) (emphasis added). I do not know what he meant by “merged.” What happened when Congress gave the Kentucky district court the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court is that such trial jurisdiction was added to the existing jurisdiction of a district court.

- Act of Feb. 19, 1803, ch. 7, 7th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 2 Stat. 201.

- Act of Mar. 25, 1804, ch. 38, 8th Cong., 1st Sess., § 8, 2 Stat. 283, 265.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1805, ch. 38, 8th Cong., 2d Sess., 2 Stat. 338.

- Act of Apr. 9, 1814, ch. 49, 13th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 3 Stat. 120, 121. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the Northern District of New York ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3.

- Act of Dec. 16, 1818, ch. 4, 15th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 3 Stat. 478. This provision did not give circuit court trial jurisdiction to the district court for the Western District of Pennsylvania with the same language used in previous statutes directly giving circuit court jurisdiction to the district courts of other districts, but the effect was the same. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the Western District of Pennsylvania ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3.

- Act of Feb. 4, 1819, ch. 12, 15th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 478, 479. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the Western District of Virginia ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176.

- Act of Feb. 6, 1839, ch. 20, 25th Cong., 3d Sess., § 8, 5 Stat. 315, 316. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the Middle District of Alabama ended in 1873. Act of Mar. 3, 1873, ch. 223, 42d Cong., 3d Sess., § 1, 17 Stat. 484.

- Act of Jan. 18, 1839, ch. 3, 25th Cong., 3d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 313. I have found no statute explicitly ending the circuit court trial jurisdiction of the Western District of Tennessee, but, if not impliedly ended in some statute, it surely ended in 1911 when the circuit courts were abolished.

- Act of Dec. 29, 1845, ch. 1, 29th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 9 Stat. 1. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Texas ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of Aug. 11, 1848, ch. 151, 30th Cong., 1st Sess., § 8, 9 Stat. 280, 281. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Georgia ended in 1872. Act of June 4, 1872, ch. 284, 42d Cong., 2d Sess. § 1, 17 Stat. 218.

- Act of Sept. 28, 1850, ch. 86, 31st Cong., 1st Sess., § 10, 9 Stat. 521, 523. Congress also gave the district courts for the Northern and Southern Districts of California “the same jurisdiction and powers which were by law given to the judge of the southern district of New York,” which did not include the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court. Id. § 2, 9 Stat. 521. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the Northern and Southern Districts of California ended in 1855. Act of Mar. 2, 1855, ch. 142, 33d Cong., 2d Sess., § 5, 10 Stat. 631.

- Act of Aug. 16, 1856, ch. 119, 34th Cong., 1st Sess., § 3, 11 Stat. 43. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of South Carolina when sitting in Greenville ended in 1889. Act of Feb. 6, 1889, ch. 113, 50th Cong., 2d Sess., § 5, 25 Stat. 655, 656.

- Act of Jan. 31, 1877, ch. 41, 44th Cong., 2d Sess., 19 Stat. 230. It is arguable that the District of West Virginia had a circuit court before 1877 because in 1864, Congress moved the terms of “the circuit court for the district of West Virginia” from Lewisburg (W. Va.) to Parkersburg (W. Va.), implying that the District of West Virginia then had a circuit court; however, what was moved might have been the terms of the district court exercising the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court. Moreover, granting circuit court trial jurisdiction to the district court for the District of West Virginia in 1877 implied that the district court for the District of West Virginia did not have a circuit court in 1864, and in 1889, Congress explicitly established a circuit court for the District of West Virginia, Act of Feb. 6, 1889, ch. 113, 50th Cong., 2d Sess. § 1, 25 Stat. 655, implying rather clearly that the District of West Virginia did not previously have a circuit court. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district courts for the Eastern District of Arkansas at Helena, the Western District of Arkansas, the Northern District of Mississippi, the Western District of South Carolina, and the District of West Virginia ended in 1889. Act of Feb. 6, 1889, ch. 113, 50th Cong., 2d Sess., § 5, 25 Stat. 655, 656.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1817, ch. 100, 14th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 390. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Indiana ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177.

- Act of April 3, 1818, ch. 29, 15th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 413. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Mississippi ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177. In 1817, Congress had given circuit court trial jurisdiction to the superior courts in the portion of the Mississippi territory called Alabama. Act of Mar. 3, 1817, ch. 59, 14th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 3 Stat. 371, 372.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1819, ch. 70, 15th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 502. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Illinois ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 176, 177.

- Act of Apr. 21, 1820, ch. 47, 16th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 564. This provision also cited “an act entitled ‘an act in addition to an act, entitled “An act to establish the judicial courts of the United States,” approved second March, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three,’” id. (punctuation altered), which changed the times and places of holding some courts, but said nothing about the jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Kentucky, Act of Mar. 2, 1789, ch. 23, 2d Cong., 2d Sess., 1 Stat. 335. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district courts for the Northern and Southern Districts of Alabama ended in 1837, Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177, when Congress established circuit courts for these districts, id. Then, in the next year, Congress abolished the circuit court for the Northern District of Alabama, Act of Feb. 22, 1838, ch. 12, 25th Cong., 2d Sess., § 1, 5 Stat. 210, and “restored” the circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for that district, id., § 2. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the Northern District of Alabama ended in 1873. Act of Mar. 3, 1873, ch. 223, 42d Cong., 3d Sess., § 1, 17 Stat. 484.

- Act of Mar. 16, 1822, ch. 12, 17th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 653. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Missouri ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177.

- Act of June 15, 1836, ch. 100, 24th Cong., 1st Sess., § 4, 5 Stat. 50, 51. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Arkansas ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 35 Stat. 176, 177.

- Act of July 1, 1836, ch. 234, 24th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 61, 62. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Michigan ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177. Section 3 of this statute did not include the District of Michigan in the list of districts for which statutes giving them circuit court trial jurisdiction were explicitly repealed. However, such jurisdiction was implicitly ended by section 1, providing the time and place for holding a circuit court in the District of Michigan, and section 4, transferring to “the several circuit courts constituted by this act” all actions that might have been brought in a circuit court and were then pending in the district courts of several districts, including the District of Michigan.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1845, ch. 75, 28th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 788. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Florida ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1845, ch. 76, 28th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 789. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Iowa ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of Aug. 9, 1846, ch. 89, 21 Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 9 Stat. 56. The circuit court trial jurisdiction of the district court for the District of Wisconsin ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of April 3, 1818, ch. 29, 15th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2, 3 Stat. 413 (“And be it further enacted, That the said state shall be one district, and be called the Mississippi district. And a district court shall be held therein, to consist of one judge, who shall reside in the said district, and be called a district judge…. [H]e shall, in all things, have and exercise the same jurisdiction and powers which were by law given to the judge of the Kentucky district, under and act, entitled ‘An act to establish the judicial courts of the United States.’”).

- Id. § 3. This jurisdiction ended in 1837. Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 3, 5 Stat. 176, 177.

- Act of Apr. 8, 1812, ch. 50, 12th Cong., 1st Sess., §§ 1, 3, 2 Stat. 701, 703.

- Act of May 11, 1858, ch. 31, 35th Cong., 1st Sess., § 3, 11 Stat. 285. This jurisdiction ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1845, ch. 76, 28th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 789.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1859, ch. 85, 35th Cong., 2d Sess. § 2, 11 Stat. 437. This jurisdiction ended in 1863. Act of Mar. 3, 1863, ch. 100, 37th Cong., 3d Sess, § 2, 12 Stat. 794.

- Act of Mar. 3, 1845, ch. 76, 28th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 789.

- Act of Jan. 21, 1861, ch. 20, 36th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2 4, 12 Stat. 126, 128. This jurisdiction ended in 1862. Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 576.

- Act of May 11, 1858, ch. 31, 35th Cong., 1st Sess., § 3, 11 Stat. 285.

- Act of May 11, 1858, ch. 31, 35th Cong., 1st Sess., § 3, 11 Stat. 285.

- In 1900, Congress twice directly gave the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court to a district court that was not an Article III court. Congress gave such jurisdiction to the district court for the judicial District of Porto Rico (as it was spelled in the statute), whose judge was then given a four-year term, Act of Apr. 12, 1900, ch. 191, 56th Cong., 1st Sess., § 34, 31 Stat. 77, 84, and to the district court for the territory of Hawaii, whose judge was then given a six-year term, Act of Apr. 30, 1900, ch. 339, 56th Cong., 1st Sess., § 86, 31 Stat. 141, 158.

- Act of Feb. 22, 1899, ch. 180, 50th Cong., 2d Sess., § 21, 25 Stat. 676, 682.

- Circuit courts were established in 1837 in the Districts of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 176, 177; in 1855 in the Districts of California, Act of Mar. 2, 1855, ch. 127, 33d Cong., 2d Sess., § 1, 10 Stat. 631; in 1862 in the Districts of Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, Act of July 15, 1862, ch. 178, 37th Cong., 2d Sess., § 1, 12 Stat. 576; in 1863 in the District of Oregon, Act of Mar. 3, 1863, ch. 100, 37th Cong., 3d Sess., § 2, 12 Stat. 794; in 1865 in the District of Nevada, Act of Feb. 27, 1865, ch. 64, 38th Cong., 2d Sess., § 1, 13 Stat. 440; in 1867 in the District of Nebraska, Act of Mar. 25, 1867, ch. 7, 40th Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 15 Stat. 5; and in 1876 in the District of Colorado, Act of June 26, 1876, ch. 147, 44th Cong., 1st Sess., § 1, 19 Stat. 61.

- Circuit courts were established in 1837 in the Southern District of Alabama and the Eastern District of Louisiana, Act of Mar. 3, 1837, ch. 34, 24th Cong., 2d Sess., § 2, 5 Stat. 176, 177.

- I have not found a reported opinion of a district court exercising the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court, but the practice is identified in opinions of the Supreme Court reviewing such decisions. See, e.g., Parsons v. Armor, 28 U.S. (3 Pet.) 413, 424 (1830). In fact, the Supreme Court once had occasion to discuss the practice when it pointed out that it would have jurisdiction to review the judgment of a circuit court affirming the judgment of a district court that “sat as a circuit court,” i.e., exercising the broad trial jurisdiction of a circuit court, but would not have jurisdiction to review a decision of a circuit court affirming a decision of a district court exercising its more limited district court jurisdiction. Southwick v. Postmaster General, 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 442, 447–48 (1829) (Marshall, C.J.). The 1789 Act gave the Supreme Court jurisdiction to review final judgments of a circuit court “removed there by appeal from a district court where the matter in dispute exceeds the sum or value of two thousand dollars.” 1789 Act, § 22, 1 Stat 73, 84. And a dissenting opinion in the Supreme Court identified the practice of indirectly giving a district court the trial jurisdiction of a circuit court by referring to the district court for the District of Kentucky “which exercised full circuit court jurisdiction.” Livingston’s Executrix v. Story, 36 U.S. (11 Pet.) 351, 396 (1837) (Baldwin, J., dissenting).

- Clay was a U.S. congressman from Kentucky in 1811–14, 1815–21, and 1823–25, and a U.S. senator from Kentucky in 1806–07, 1810–11, 1831–42, and 1849–52. David S. Heidler, Henry Clay—American Statesman, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henry-Clay.

- Surrency, supra note 38, at 43 & nn.2, 3 (quoting Thomas H. Benton, Abridgement of the Debates of Congress 160, 165 (1860)).

- Another possibility is that referencing the jurisdiction of the district Court for the District of Kentucky would enable a future Congress to change the jurisdiction of all the district courts that had been given the same circuit court trial jurisdiction as the Kentucky court by a simple provision that changed the jurisdiction of the Kentucky court. However, if all those courts had been directly given the trial court jurisdiction of circuit courts (without a reference to the Kentucky court), a change in their jurisdiction could just as simply have been made by one provision altering the jurisdiction of all district courts that had been given the trial court jurisdiction of a circuit court.

- Even Mary Tachau’s meticulously researched book on the early history of the District of Kentucky, Federal Courts in the Early Republic: Kentucky, 1789-1816 (1978), makes no mention of the district serving as a statutory reference for giving circuit court trial jurisdiction to several district courts.

- A similar example of legislating with respect to federal courts by an indirect method can be found as recently as 1977 when Congress, placing the District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands in the Ninth Circuit, provided that the District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands “shall constitute a part of the same judicial circuit of the United States as Guam,” Pub. L. No. 95-157, § 1(a), 91 Stat. 1265, 1265, which Congress had placed in the Ninth Circuit in 1951, Act of Oct. 31, 1951, ch. 655, Pub. L. 248, § 34, 65 Stat. 710, 723; see also Guam Organic Act of 1950 § 23(a), 64 Stat. 384, 390 (authorizing Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to hear appeals from the District Court of Guam).