by Steven S. Gensler, Patrick Higginbotham and Lee Rosenthal

Vol. 104 No. 2 (2020) | Coping with COVID | Download PDF Version of Article

A jury of 12 resonates through the centuries. Twelve-person juries were a fixture from at least the 14th century until the 1970s.1 Over 600 years of history is a powerful endorsement.2 So too are the many social-science studies consistently showing that a 12-person jury makes for a better deliberative process, with more predictable (and fewer outlier) results, by a more diverse group that is a more representative cross-section of the community. To that, add the benefit of engaging more citizens in the best civics lesson the judiciary offers. To all of that, add our common sense telling us that 12 heads are better than six, or eight, or even ten.

History. Social science. Civics. Common sense. That’s a powerful quartet. And yet, most federal judges today routinely seat civil juries without the full complement of 12 members. Why? Because in 1973 the United States Supreme Court said it was okay. Since then, the smaller-than-12-person jury has become a habit. For many courts, it has become the default.

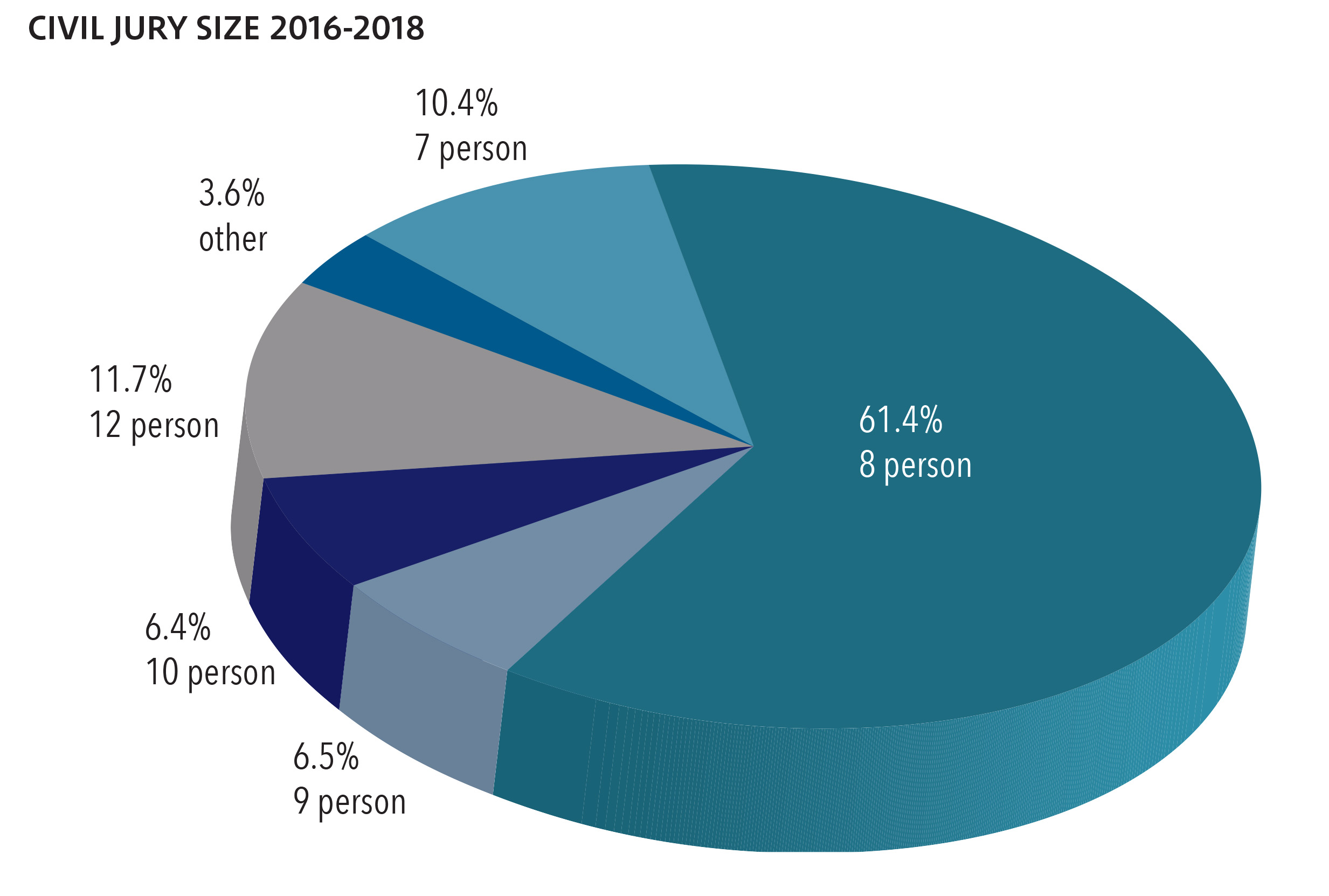

To test our shrunken-jury hypothesis, we gathered data from 15 federal districts over the three years from 2016 to 2018. The results are dramatic and confirmed our worst fears. Over 60 percent of the trials in our study were to juries of eight. It is the new normal. No other size jury comes close. Only one in eight civil trials is still heard and decided by the traditional 12-person jury. At the same time, the percentage of civil cases that end in a jury trial continues to plummet, dropping to less than 0.5 percent last year.3 The result is that we are trying ever fewer civil cases to ever fewer jurors.

Federal judges often put the most complicated, high-stakes cases in the hands of smaller juries. Of the ten largest damage awards in civil cases tried to juries in federal courts in 2019, seven were by eight-person juries; one was by a seven-person jury; one was by a nine-person jury; and one was by a six-person jury.4 None of those cases was tried to a 12-person jury. We are not saying any of these cases was wrongly decided. These examples simply show that the smallest juries can be, and are, asked to decide some of the biggest cases. History, social science, civics, and common sense all tell us we have lost our way. Smaller juries should be the exception, and larger juries the rule. We can change course, and we should do it quickly. At the end of this essay, we offer three concrete steps we think can help.

To be clear, we don’t propose requiring a 12-person jury in all civil cases. Rule 48 — which provides that a “jury must begin with at least 6 and no more than 12 members,” and that a verdict be returned unanimously “by a jury of at least 6 members” — rightly allows more flexibility than that. We want to remind judges, emphatically, that the choice is theirs to make. We ask that judges carefully consider the benefits of 12 as the gold standard, and not simply default to six, or eight, or ten. And we hope that, for most cases, 12 will be the number.

The 12-person jury is a tradition tracing back to at least 1066, when William the Conqueror brought the practice of trial-by-jury in civil and criminal cases to England.5 Initially, jurors were more like witnesses in that they were picked because they knew something about the facts at issue.6 By the 1500s, jurors no longer decided cases based on their own knowledge, but based on the information they received in court.7 Over time, jury service in England came to be viewed as “the most representative institution available to the English people.”8 Throughout the evolution of the English civil jury, the traditional number of jurors held constant at 12. William Blackstone summarized the importance of trials by 12 jurors in his Commentaries:

[A] competent number of sensible and upright jurymen, chosen by lot from among those of the middle rank, will be found the best investigators of truth, and the surest guardians of public justice. For the most powerful individual in the state will be cautious of committing any flagrant invasion of another’s right, when he knows that the fact of his oppression must be examined and decided by twelve indifferent men . . . .9

The English colonists brought the jury-trial right, with 12-person juries, with them. In the colonies, the right became even more important than in England because it served as a shield and protection against British oppression.10 The Declaration of Independence listed Britain’s efforts to deny the colonies “in many cases, of the benefits of trial by Jury” as one of the reasons justifying the revolt.11 During the colonial period, the traditional number of jurors remained constant at 12.12

After the Revolution, all of the 13 original states continued the right to a civil jury trial in different fashions.13 The original Constitution, of course, contained no express provisions guaranteeing civil juries in the federal courts, and that omission proved costly as it gave the Anti-Federalists one of their strongest arguments against ratification.14 The omission was rectified by the adoption of the Seventh Amendment, which preserves civil jury rights as they existed at common law.15 And “it was the settled understanding at the time the Seventh Amendment was drafted that a jury was comprised of twelve, no more and no less.”16 For the next 180 years, the constitutional requirement of a traditional 12-person jury in federal civil cases was virtually unchallenged. The Supreme Court did not often discuss civil juries during this period, but whenever it did, it clearly had 12-person juries in mind.17 In 1938, the 12-person-jury assumption became enshrined in Rule 48 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which told parties that they could “stipulate that the jury shall consist of any number less than twelve.”18 By all accounts, judges and litigants alike took it as gospel that a civil jury in federal court would have 12 members unless the parties agreed to a lesser number, and few ever did.19

Things changed in the early 1970s, dramatically, quickly, and unexpectedly. The 12-person standard started to erode when the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a six-person state-court criminal jury in Williams v. Florida.20 In Williams, the Court held that the tradition of 12-person juries was a “historical accident, unnecessary to effect the purposes of the jury system, and wholly without significance ‘except to mystics.’”21

The Court held that smaller juries were constitutional so long as they provided the same function as a traditional 12-person jury.22 Based on its reading of the social-science literature of the day, the Court saw no loss of functionality, and therefore no reason to prevent states from pursuing the cost savings many claimed smaller juries would deliver.23 As discussed below, the consensus among social scientists then and since is that this was lousy social science and unwise policy.

While Williams involved criminal juries in state courts, it was clear to everyone that the decision’s rationale would apply equally to civil juries in federal court. Working from that premise, in 1971 the United States Judicial Conference took the position that civil juries should have six members unless the parties stipulated to an even smaller number.24 By the end of 1972, 56 of the 94 federal districts had changed their local rules to permit six-person juries in civil trials.25 In 1973, the Court held in Colgrove v. Battin that the Seventh Amendment permitted six-person juries in civil cases, embracing the same functional approach it developed in Williams.26 Here too, the Court read the social science as supporting (or at least not contradicting) the conclusion that six-person juries were just as good as 12-person juries, formally freeing districts from any constitutional obligation to seat 12-person civil juries.27

After Colgrove, the rout was on. The Judicial Conference pressed Congress for legislation setting the size of civil juries at six.28 By 1978, just five years after Colgrove, 80 of the 95 districts had adopted local rules authorizing juries of as few as six.29 Awkwardly, Rule 48 continued to speak in terms of allowing parties to stipulate to juries of fewer than 12, though the clear practice in the field was for courts to make the choice for them. In 1991, the text of Rule 48 was amended to catch up with the reality on the ground, providing: “A jury must begin with at least 6 and no more than 12 members.”30 During the mid-1990s, the Civil Rules Advisory Committee (chaired by Judge Patrick Higginbotham) led an effort to amend Rule 48 to return to tradition and require 12-person juries. But that effort came up just short of the finish line when the proposal was narrowly rejected by the Judicial Conference.31

And that’s where things stand today. But it is important to understand just where things stand. The Supreme Court has never said that the Seventh Amendment requires smaller juries. Nor has the Court ever spoken against the traditional 12-person jury.32 All the Court has ever said is that the Constitution permits judges to empanel smaller juries if they choose. Rule 48 sends the same message. That’s the key point. Whether to empanel six or 12 or some number in between is a choice for the judge to make.

How are federal judges using the discretion the Supreme Court has twice given them — first through its interpretation of the Seventh Amendment, and then again through the 1991 amendment to Rule 48? The longstanding sense is that smaller juries have become the norm. That was our sense, too. But when we went to look at the data, we found none. Nobody had collected it.33 We decided to change that.

Thanks to extraordinarily helpful Clerks of Court, we collected jury-size data from 15 federal districts from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2018. We selected the districts to get a representative sample considering geography, the size and mix of the district’s civil docket, and population. Our sample includes districts covering major coastal cities like the Southern District of New York and the Central District of California; smaller districts like the Middle District of Florida and the Western District of Oklahoma; and districts mixing large urban and widespread rural areas like the District of Arizona, the District of Minnesota, and the Southern District of Texas.

As shown in Table 1 [below], in the 15 districts in our study, there were a total of 1,831 civil jury trials from 2016 to 2018 (and 22 in 2019). Of those, just 11.7 percent (214) began with juries of 12. Even adding in those that began as juries of 13 or 14, the total percentage of juries that began with at least 12 members was still just 12.3 percent (226).34

Taking it one step further and adding in juries of 10 and 11, the percentage of juries that began with 10 or more members still totals only 20.0 percent (366). That means that only one in five juries began with ten or more members.

At the other end of the spectrum, juries that began with just six members were rare. Just 1.6 percent (30) of the juries began with only six members, perhaps because of the fear of a mistrial if any of the jurors was discharged and the parties would not stipulate to a verdict by fewer than six.35 Moving higher on the scale, 10.4 percent (191) of the juries began with juries of seven. And, most significantly, 61.4 percent (1,125) of the juries began with eight members. Completing the spectrum, 6.5 percent (119) of the juries began with nine jurors.

The numbers tell a clear story. In total, four out of every five civil juries begin with nine or fewer members. By far, the most common size of civil juries today is eight. It is the number in the majority of cases (over 60 percent), and no other number even comes close. Courts are over five times more likely to empanel a jury of eight than they are to empanel a jury of 12. In short, juries of eight are the new normal, and anything else is the exception.

These statistics hold up when analyzed across the type of suit. As shown in Table 2 (below), for example, civil- rights cases make up the largest category in the data set, with a total of 703 jury trials. Of those, 74.1 percent (521) began with juries of eight or fewer, while only 13.9 percent (98) began with juries of 12 or more. Contract cases make up the next largest category, with a total of 308 jury trials. Of those,68.8 percent (212) began with juries of eight or fewer, while only 14 percent (43) began with juries of 12 or more. The same pattern emerges with torts (personal injury and personal property) cases, the third largest category with a combined total of 298 jury trials. Of those, 71.8 percent (214) began with juries of eight or fewer, while only 11.7 percent (35) began with juries of 12 or more. In virtually every subject category, juries of eight or fewer were used a majority of the time. In no subject category does the rate of 12-person juries come close to the rate of eight-person juries.

These trends also hold up across most of the individual districts we examined, with some notable exceptions. In 12 of the 15 districts in our study, juries of eight or fewer were used in at least half of the cases. Eight of those districts used juries of eight or fewer more than 80 percent of the time. Two districts (CA-C and OK-W) used juries of eight or fewer more than 90 percent of the time. In contrast, eight districts used juries of 12 or more less than three percent of the time. In those eight districts, the total numbers of juries with 12 or more members were three (NY-S), 2 (AZ), 1 (CA-C, CA-N, FL-S), and zero (OH-S, OK-W, OR). But the data also reveal that a culture of using 12-person juries has held firm in some districts. The District of Minnesota, for example, used juries of 12 or more in 82.4 percent of its civil jury trials during our study period. Juries of 12 or more were also the majority in OH-N (66 percent). Those were the only districts in our study in which juries of 12 or more outnumbered juries of eight or fewer.

So now we know. Juries have shrunk. Most of the time, eight is the number. But is it the right number? The answer from the social-science community has always been a resounding no. For nearly 50 years, social scientists have been saying that the Supreme Court got it wrong when it said that smaller juries were “just as good” as larger ones. It’s worth reminding ourselves what we lose when courts seat shrunken juries.

The Supreme Court cited to several social-science “experiments” in Williams as supporting its conclusion that there were “no discernible difference[s]” between 6- and 12-person juries on the factors that mattered.36 That assertion was deeply flawed. As leading jury expert Professor Hans Zeisel showed, the items the Court cited were not empirical studies but rather conclusory statements by the authors, supported at best by limited experience and anecdote.37 Indeed, as Zeisel explained, the Court’s assertions were not merely unsupported — they were wrong.38 Yet three years later, the Court doubled down on its “no discernable difference” hypothesis in Colgrove, this time citing additional studies it said provided “convincing empirical evidence” that it was right.39 Once again, the social science community voiced its disapproval.40 The years following the Williams and Colgrove decisions saw a flurry of social-science experiments on whether reducing panel size affected jury function.41 Virtually all of these studies show, contrary to the Court’s conclusions, that larger and smaller juries are not functionally equivalent.42

One major difference is that larger juries are more predictable and less likely to render outlier awards. Six-person juries are four times more likely to return extremely high or low damage awards compared to the average.43 If a juror has an extreme view on damages, that view can pull the group’s award in that direction. The smaller the jury, the greater the force of a single juror’s pull, and the greater the chance the jury will return an outlier award on both the low and high ends. In contrast, damage awards by larger juries are more likely to cluster toward the middle range of awards.44

The outlier problem is significant. First, juries are the voice of the community.45 They are perhaps the most important way for the community to express its views on who has been wronged, who should be held accountable, and how. Since the community can’t participate as a whole, we select a representative group of people and let them speak for the community. A jury’s decision is best, then, when it hews closely to the views of the community it represents. Larger juries are more likely to reach verdicts closer to the consensus view.46 Second, the increased chance that a small jury might return a verdict outside of community norms undermines faith and trust in the system. One of the major complaints of those deciding whether to file and try a civil dispute is whether the court system produces intolerably unpredictable and variable results.47 Greater unpredictability is the predictable result when courts use shrunken juries.

Larger juries aren’t just more predictable; they likely make better decisions. Social science shows that for many kinds of decision tasks, the larger a workable decision-making group, the better the decisions will be because of the increased resources more group members provide. If six heads are better than one, 12 are in most respects better than six or eight. Larger juries recall the evidence more accurately, recall more probative information, and rely less on conclusory statements and nonprobative evidence.48 The studies do show a slight increase in deliberation time, and some have cited that as a disadvantage of larger juries.49 But the effects are small and unlikely to significantly increase costs. And given that the parties’ fates and fortunes are on the line, evidence that larger juries spend more time deliberating might be seen as a virtue, not a vice.

Larger juries are also more inclusive and more representative of the community. In Williams and Colgrove, the Court acknowledged the value of minority representation on juries but concluded that reducing the size of juries would have at most a negligible impact.50 Basic statistical modeling shows that conclusion to have been glaringly wrong. In reality, cutting the size of the jury dramatically increases the chance of excluding minorities.51 The increase depends on the percentage of that minority in the community. For a minority group that is 30 percent of a community, there is about a 1.4 percent chance that a 12-person jury will not include a member of that group. But if you cut the jury in half to six, the chance of exclusion doesn’t just double, it goes up to 11.8 percent, making exclusion eight times more likely. For a minority group that is 20 percent of a community, there is about a 6.9 percent chance that a 12-person jury will have no member of that group. Cut the jury to six, and the chance goes up to 26.2 percent. For a minority group that is 10 percent of a community, cutting the jury to six results in over half of the juries (53.1 percent) having no member of that group.

The studies that have looked at the impact of jury size on minority representation have confirmed that smaller juries are more likely to have no member of the minority group in question.52 The effect is most pronounced when a jury has only six members. But it is also highly significant when a jury is reduced to eight members (the modal number in the districts in our study).53 Here are two examples. A study from California found that 20 percent of eight-person juries had no black juror, compared to 8.7 percent of 12-person juries. In another study, a Cook County Circuit Court judge systematically tracked jury composition data from 277 civil jury trials held over six years from 2001 to 2007.54 Because 25 percent of the venire pool was black, one might imagine that every jury (whether six or 12) would include at least one black juror. But, in fact, 28.1 percent of the six-person juries lacked even a single black juror.55 In contrast, only 2.1 percent of the 12-person juries had no black jurors.

The Court made another serious social-science mistake in Williams and Colgrove when it assumed that the value of community representation would be functionally served so long as a single minority member was on the jury.56 The social-science research, then and now, tells us otherwise. Studies show that the ability of a dissenting voice to withstand group pressure is greatly increased when a second dissenting voice is added.57 On their own, people who see things differently tend to buckle and conform. With even a single ally, they are much less likely to cave to the group. In other words, a single person who sees things differently than five others is in a much weaker position than two people who see things differently than ten others.58 Though the point is obvious, it is worth stating: it is statistically much harder for a dissenting juror to find an ally in a six- or eight-person jury than in a 12-person jury.59

The last remaining argument against larger juries is that they are more likely to hang. Interestingly, the available studies show that while that is true, the effect is much smaller than expected.60 But the more important question is what conclusion we should draw when a jury does hang. Should we take it as signal that the system failed or that it succeeded?61 Should we assume that the holdout(s) stopped the others from getting it right, or should we acknowledge the possibility that the holdout(s) stopped the others from making an unjust decision? No empirical analysis has ever answered, or is ever likely to answer, those questions. For that reason, we cannot know whether a lower incidence of hung juries is a virtue of smaller juries or a vice. And if we should ever conclude that “holdouts” are a bug in the system rather than a feature, it would be better to deal with the matter directly by altering the unanimity requirement than by sacrificing the uncontested benefits of larger juries.

In 2020, the case for returning to the 12-person jury is stronger than ever. In this era of vanishing civil trials, the arguments in favor of 12-person juries are even more compelling. In contrast, the supposed benefits of smaller juries, never strong, grow weaker every year as courts find more efficient ways to administer the few jury trials we still have.

First, whatever doubts people may have had before about the negative effects of smaller juries, the ongoing social-science and empirical research should make clear that those negative effects are real. Every study since 1996 has supported the prior research and the underlying statistical and decision-making theories. No new study or new theory refutes them. The jury- research community remains steadfast in concluding that smaller juries are composed differently and act differently than larger juries. It’s time to stop doubting those findings. It’s time to fully resist the appeal to anecdotes and individual observations. Larger juries are better than smaller juries in ways important to the process and the product.

Second, in an age when fewer and fewer civil cases are tried, each civil jury trial takes on added importance. In 1970, when Williams was decided, 4.3 percent of federal civil cases were tried to a civil jury.62 By 1995, when the Advisory Committee proposed amending Rule 48 to require 12-person juries, the civil jury-trial rate had dropped to 1.8 percent.63 It now stands at just 0.5 percent.64 Of the 306,304 civil cases that terminated during the 12-month period ending December 31, 2019, only 1,534 of them reached a jury.65

As Professor John Langbein put it, “we have gone from a world in which trials, typically jury trials, were routine, to a world in which trials have become ‘vanishingly rare.’”66 Fewer jury verdicts means fewer data points on liability and damages. These are critical signals to parties and lawyers about how to evaluate similar cases, whether to settle, and on what terms. Outliers — in either direction — exert an even greater influence as the number of verdicts shrinks. We should avoid them if we can. Returning to 12-person juries will help do that.

Third, fewer jury trials also means fewer opportunities for citizens to serve as jurors. Civil jury service is one of the truly exceptional features of the American justice system.67 Civil jury service is the closest most Americans ever get to having their own say in expressing and defining community norms.68 People who serve on juries consistently say that the experience makes them more appreciative and more trustful of the court system.69 In this era of declining jury-trial rates, we should fill every jury chair we can, every chance we get. Every empty jury chair is a missed opportunity to strengthen the bonds between the people and the courts.

Fourth, we should choose inclusiveness and broader representation. We know that smaller juries are more likely to be more homogenous and lack even a single member of a minority group that constitutes a significant part of the community. We should move in the direction of making sure that the few jury trials we do have are more representative of the community, not less. As Professor Shari Diamond put it, “[i]f increasing diversity in order to better represent the population is a goal worth pursuing for the U.S. jury, the straightforward solution — the key — is a return to the 12-member jury.”70 Fifth, the cost arguments against larger juries have always been weak. Jury trials consume a tiny fraction of the court’s budget. This is not the place to pinch pennies. That was true in the 1970s when the Court and the Judicial Conference first latched onto the cost-savings rationale for smaller juries,71 and it remains true today. But even the most cost-conscious should consider modern factors that have already slashed the amount federal courts spend on civil juries. Most obviously, we are already spending comparatively less on civil juries because we have fewer of them. Since 1970, the civil jury-trial rate has dropped from 4.3 percent to 0.5 percent. We can afford to invest in the few civil jury trials we are fortunate enough to still have, while we still have them.

Moreover, seating a smaller jury just doesn’t save the judge or the parties much time or expense.72 Studies show that the time saved during voir dire and selection is negligible, at most a matter of a few minutes.73 And changes in technology have already reduced the cost of assembling venire panels and picking juries, far more than shrinking jury size ever could. From delivery of the jury summons and jury questionnaires to applications to be excused or have jury service postponed, much of the time- and labor-intensive “paperwork” is now done electronically. It just takes fewer court personnel less time to manage juries than it used to take.

To recap, we know that larger juries are better than smaller juries in ways that really matter. And we know that the time and expense saved by seating a smaller jury is minimal at best. But our data clearly show that most judges are not choosing to seat full juries. How do we change that? How do we flip the model and make 12-person juries the default and not the exception? An essential first step is to keep reminding judges and lawyers of what is at stake.74 During the heyday of the jury-size debate, articles like this were common. Not anymore. We don’t want to let all that we’ve learned about the benefits of 12-person juries fade away and become forgotten. It is not yesterday’s news. The topic is as timely and important today as it was in the 1970s or the 1990s, even more so in this age of vanishing civil jury trials. As a starting point, we have three suggestions:

Add Civil Jury Size to the Curriculum of Baby Judge’s School. Our first suggestion is simple and could be implemented immediately. We can’t think of a better place to start than to have jury size added to the curriculum of “Baby Judge’s School,” the training sessions for new (and pretty new) federal judges. This may be the best way to make a difference in the long run. Experience shows that judges are reluctant to alter their jury-trial practices once they become fixed.75 That makes it vital to reach judges when they will be most open to considering all of the alternatives.

As new judges begin to adopt their own jury-trial practices, they should know that there is a choice to be made and that they can choose to seat 12-person juries, even if the culture and practice in their court is to seat smaller juries. It is equally critical that new judges know the social science demonstrating what is gained when judges seat a full 12-person jury. Without this information, we expect many new judges would understandably follow past practice in their home district, without giving much thought to what their own practices should be, and perhaps without even realizing that the choice is theirs to make. And as new judges make informed decisions for themselves, it is essential that they learn the history, social science, and civics that will allow them to make a fully informed choice.

Revise the Benchbook, the Civil Litigation Management Manual, and the Handbook on Jury Use. Reminded of the jury-size debate, trial judges at all levels of experience can and should make their own informed choices, and not just follow what they otherwise may see as the norm. Unfortunately, if a judge were to seek guidance from the federal judicial resources available today, those resources would not be of much help.

For example, a federal district judge might turn to the Benchbook for U.S. District Court Judges, a resource billed as “a concise, practical guide to situations federal judges are likely to encounter on the bench.”76 It includes a helpful chapter on how to select a civil jury, but it contains no discussion of how large the jury should be or the factors the judge might consider in making that choice.77 That same judge might also turn to the Civil Litigation Management Manual developed by the Judicial Conference’s Committee on Court Administration and Case Management.78 It too contains a helpful discussion of jury trials, but it is devoted to techniques for judicial management of what happens during the trial, with no discussion of the process for seating the jury in the first place.79

A truly intrepid judge might track down a 1989 Federal Judicial Center publication titled Handbook on Jury Use in the Federal District Courts.80 That would seem like an ideal resource to learn about jury size issues. The Handbook does address jury size, but it says only this: “Rule 48 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure allows parties in civil cases to agree to a jury of any size and to a non-unanimous verdict. Almost all of the federal district courts have local rules that provide for 6-member juries in civil cases, and such rules have been upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.”81

There is no mention of the jury-size debate or the choice to be made. On the following page, the Handbook provides an example of how to calculate how many panel members to call to seat a jury, considering challenges for cause, peremptory challenges, and the seating of alternates (still the practice then). The example leads to a 6-person jury and implies that it is the norm in “routine civil cases.”82

To be clear, we don’t fault any of these publications individually for what they say. The problem lies in what they collectively do not say. None reminds judges that Rule 48 gives them a choice on the size of the jury to empanel. None addresses the pros and cons of jury size. Not a single word. We hope that, at the very least, the Benchbook and the Manual would be revised to remind judges that they may choose to seat a traditional jury of 12 and include some meaningful discussion of jury size. We also encourage the Federal Judicial Center to consider issuing a new edition of the Handbook to include a full discussion of the benefits of larger juries and to revamp the illustrations, so as not to send unintended signals that smaller juries are preferred.

Add Civil Jury Size to the Programs at Bench/Bar Conferences, Workshops, and Similar Exchanges. We encourage judges and lawyers to add this topic to the menu of topics addressed at different bench and bar events, continuing education programs, and similar exchanges. Lawyers can be reminded that they can ask for a jury of 12. It’s their voice. Judges can be reminded that they have the authority to seat a jury of 12, even if the lawyers don’t ask for it. It’s their choice. Everyone can be reminded of the many reasons why the jury system works better with 12. A good conversation is rarely a bad thing; here, it could really help.

Over the last 40-plus years, the 12-person civil jury has gone from being a fixture in the federal courts to a relative rarity. We should all be concerned. That the Supreme Court has allowed us to use smaller juries does not require us to use them. We can use 12-person juries. The benefits are large; the disadvantages marginal. We’re not suggesting this as a rule or a requirement. We are simply suggesting that judges not reflexively pick six, or eight, or even ten, and instead remember their authority to seat 12. And the great benefits of doing so.

As civil jury trials resume, some may urge us to bring them back in even smaller form. These arguments are easy to understand. Smaller juries require smaller venire panels. Jury selection and trial with social distancing may be easier to achieve with a smaller jury. We cannot ignore these points. Nor can we minimize the important role of social distancing in these difficult times. But we should be careful not to let these short-term concerns overtake everything else or chart our long-term path.

First, we have to be able to seat 12 in order to have a criminal jury, and that means we can do it in civil cases as well. What we learn in one setting will help with the other.

Second, during the transition period and as the pandemic wanes, civil trials will be even fewer and rarer than before. That makes the ones we will have even more critical, for all of the reasons explored above. We urge courts to carefully consider the strong reasons to, and the ways they can, pick and seat full juries while also responsibly managing social distancing.

The pandemic will end. When it does, we should be ready, including by having a robust, thriving civil jury system that will serve us all, in 2021 and well beyond.

Footnotes: