Taking Center Stage: The Virginia Revival Model Courtroom

by Justine Parry Welch and Robert J. Conrad Jr.

Vol. 105 No. 3 (2021) | Leaving Afghanistan | Download PDF Version of Article

“We shape our buildings, and afterwards, our buildings shape us.”

— WINSTON CHURCHILL1

The courtroom layout affects more than the mere structure and architecture of the space. Norman Spaulding, the Sweitzer Professor of Law at Stanford Law School, once wrote: “Beyond the question of jurisdiction, which sovereignty implies, and the right of exclusion, which private property entails, precious little is said in legal theory about the relationship between justice and the space in which it operates.”2 That space is a configuration of the relationship between the jury and the witness.

Through the eyes of a lay individual, the dynamics of the courtroom exist according to their face value: The judge sits above and facing everyone, so he must be the ultimate source of power and decision-making. The lawyers move around, front and center, when they speak, often addressing the judge, so they present the next source of authority in this rally of arguments and objections. Then, off to the side, sits the jury. Rarely addressed directly, except at the beginning and end, the jury’s actual role is a bit illusive. Likely, at least one juror dozes off at some point during the trial. Their eyes glaze over as they sit and observe, like an onlooker watching a boxing match taking place inside a ring. Never are they at the center of the action. The judges and lawyers are the stars of the show. The judge may say the jury matters, but the jury’s sidelined position says otherwise.

A jury trial represents a vital American contribution to law and liberty.3 The jury system lends democratic legitimacy to the justice system.4 Books, movies, plays, and songs celebrate it.5 Yet trial practitioners know that real-life courtroom drama often eclipses fiction. Although criticisms call into question the jury’s very existence,6 the jury endures as a timeless example of democratic ideals — “the lamp that shows that freedom lives.”7 Thus, careful attention must be paid to the space within which jury trials occur and judicial democracy finds its roots. After all, “[t]he space in which justice is done shapes what we think it means.”8Courthouses serve as monuments to our legal tradition, so a willingness to reconsider design assumptions and unexamined practices is essential to the continuing vitality, indeed renewed energy, of jury trials.9 “Architects and those commissioning buildings have long understood the importance of space and place in creating and reinforcing courtroom identities, but this study of court architecture encourages the reader to confront the interface between rhetoric and reality.”10

We — Judge Robert J. Conrad, Jr., and attorney Justine Parry Welch — advocate a re-engagement with a courtroom design that has come to be known as the Virginia Revival Model (VRM) — a long-used, prominent design of county courthouses in the Commonwealth of Virginia. We propose that present-day needs, historical design, and philosophical considerations support resurrecting broader use of the VRM.

This essay focuses on the organization of the space where justice is sought: courtroom design. Law Professor Linda Mulcahy writes that “[s]patial dynamics can influence what evidence is forthcoming, the basis on which judgments are made, and the confidence that the public has in the process of adjudication.”11 Essentially, she says, “the environment in which the trial takes place can be seen as a physical expression of our relationship with the ideals of justice,” yet academics have paid very little attention to the geopolitics of the trial.12 This essay posits that intentional courtroom design matters to the resolution of disputes and the search for truth. As Mulcahy writes, “Understanding the factors which determine the internal design of the courtroom are crucial to a broader and more nuanced understanding of state-sanctioned adjudication.”13

First, we introduce the VRM, unpacking its organization and function. Then we trace the history of this courtroom model through the evolution of the American courtroom, before exploring the philosophy behind the VRM architecture. And finally, we set forth the effects of this model, as well as its role both in courtroom dynamics and in the pursuit of justice, to show readers the benefits — and necessity — of a VRM revival in American courthouses.

The Virginia Revival Model

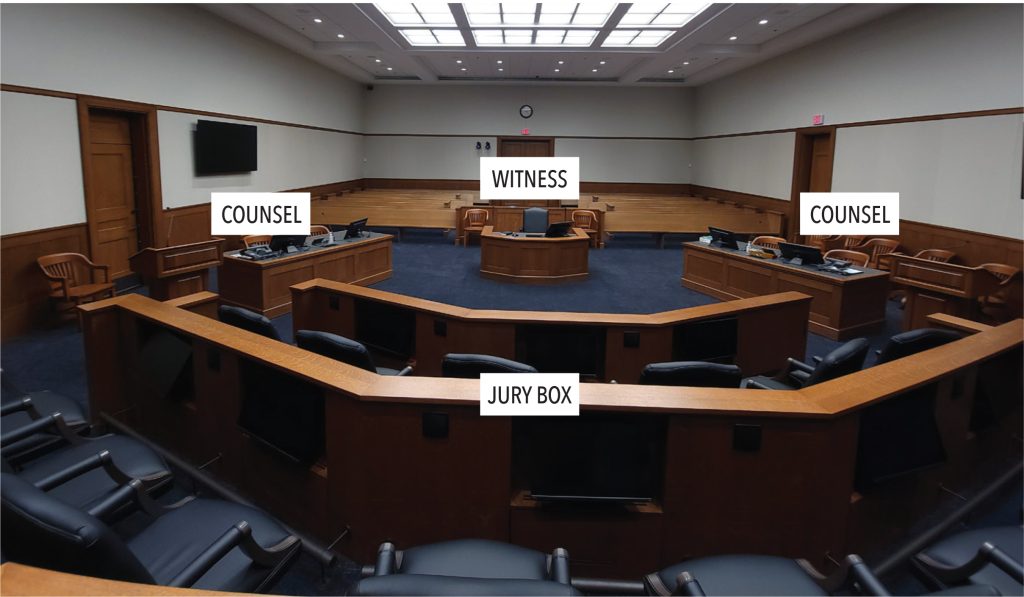

What is the VRM? Its distinguishing feature is the centered jury box. The counsel tables sit off to the side, and the jury box is positioned underneath the judge, facing the witness box, which is centrally located. This center placement recognizes the centrality of the jury’s role and duty as the ultimate fact-finder. More importantly, it emphasizes the democratic notion of citizen participation in the quest for justice. This beholden status of the jury, reflected in the architecture, is what initially drew us to this design.

The project to rethink courthouse design grew out of Judge Conrad’s service on the Space and Facilities Committee of the Judicial Conference. During his six-year tenure, committee members considered courthouse construction concepts, applied that thinking to the new courthouse construction, and then applied that discussion to a courthouse in Charlotte (Western District of North Carolina). Gradually, Judge Conrad and a team of architects, lawyers, and staff concluded, after years of study, that the VRM is a superior design and belongs in the U.S. Courts Design Guide as an optional courtroom layout.

For most of that time, the VRM project for Charlotte languished on the judiciary’s “Five Year” Plan. In theory, that plan includes projects anticipated to be constructed in the next five years; however, the federal courthouse in Charlotte sat on the list for 20 years. Then, in the Omnibus Appropriations Bill of 2016, Congress authorized the construction of eight new courthouses.14 Charlotte was one of those eight projects.

The design team, led by Judge Conrad, toured numerous courthouses across the country with an eye for design features, or “fittings,” that would improve the administration of justice in future courthouse construction — and, more specifically, would improve courtroom construction.15 Throughout these tours, our team compared courtroom features in search of the most effective design, endeavoring to discover an approach that best embodied the values of the justice system while simultaneously complying with the demanding federal U.S. Courts Design Guide specifications16 and the Americans with Disabilities Act.17 In short, we did everything modern-day courts do in anticipation of new courthouse construction — and one additional thing: We rethought the layout of the courtroom.

Throughout this lengthy, informative, and valuable period of investigation, I, Judge Conrad, kept in mind my own experience as a young attorney practicing in the Albemarle County Courthouse in Charlottesville, Virginia. Designed by Thomas Jefferson, and built in 1803, the Albemarle County Courthouse has been in continuous use for the past two centuries. This particular courthouse features a unique courtroom layout, including a centered jury box, which left an indelible impression on me as a practicing lawyer. Here is where I first experienced and came to admire what has come to be known as the Virginia Revival Model courtroom design. And this was the model we eventually concluded was the best fit for the new courthouse in Charlotte.

History of the VRM

Our research process included touring the Albemarle County and City of Charlottesville courthouses, as well as talking to judges and attorneys practicing in those venues. We consulted architectural historians; studied books on design and the history of courtrooms in the colonial period; surveyed colonial art depicting courtrooms; and drew inferences concerning courtroom architecture in the colonial period. What emerged from this organic study was a recognition of the intentionality behind the VRM. As that understanding set in, the case for the VRM became even more convincing.

History informed us that the Albemarle County Courthouse was a continuation of a purposeful courthouse design initiated during the colonial period in the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Tidewater area and then implemented in the capital, which was then Williamsburg,18 and eventually throughout the rest of colonial Virginia.

THE ALBEMARLE COUNTY COURTHOUSE IS ONE OF SEVERAL VIRGINIA COURTS TO FEATURE A VIRGINIA REVIVAL MODEL COURTROOM LAYOUT, WITH THE JURY BOX IN FRONT OF THE JUDGE’S BENCH RATHER THAN TO THE SIDE. (PHOTO BY ERIC W. AMTMANN AIA | DALGLIESH GILPIN PAXTON ARCHITECTS)

The American justice system began as a simple table-and-chairs arrangement, with the witness standing in front of the clerk. From this early spatial template, the VRM evolved. The historical purposes of the spatial organization — symbolizing shared authority with the judge, increased importance, and overall centrality of the jury — hold true today. George Cooke’s 1834 painting, Patrick Henry Arguing the Parson’s Cause at Hanover Courthouse (right),19 illustrates the VRM in action.20

Toward the center of Cooke’s painting, attorney Patrick Henry stands in the second tier of wooden benches of the lawyer’s bar as he tries his first case.21 The clerk of court is shown working at a centralized wooden table, and the jury sits directly behind him.22 This placement of the jury bench behind the clerk and below the judge’s bench was a change from the standard practice in other 18th-century American courtrooms, in which the jury sat in an enclosed “box” made up of two or three rows of benches located off to the side of the judges’ bench — the “traditional model,” as known today.23

DETAIL OF “PATRICK HENRY ARGUING THE PARSON’S CAUSE AT HANOVER COURTHOUSE,” PAINTING BY GEORGE COOKE, CIRCA 1834.

Virginia’s unique placement of the jury bench in the early 18th century aligns with the era’s architectural experimentation. That experimentation took two forms. First, a movement toward exterior permanence as reflected by brick and mortar replacing wooden construction. Second, interior “fittings” were refined as the prevalence of jury trials, and concomitant importance of juries, increased. As to the latter, as historian Carl R. Lounsbury writes, a wave of courtrooms had “shed their domestic and makeshift appearance in favor of interiors customized for the increasingly complex routing of court business.”24 By the end of the 18th century, the “replacement of impermanent wooden structures with larger and more costly masonry ones” was a characteristic pattern of development that started in the 17th century and continued through the Civil War.25

Thomas Jefferson found this replacement process necessary because he believed “a country whose buildings are of wood can never increase in its improvements to any considerable degree.”26 “Half a century later, masonry buildings, many of them . . . inspired by Jefferson’s ideas, designs and workmen, had supplanted nearly all of the smaller wooden courthouses throughout the Commonwealth,”27 writes Lounsbury. A sense of permanence and authority took over courthouses’ external designs, and the intentionality used to establish these new external characteristics reached inside the courthouses by employing the same architectural experimentation in the interior fittings of the courtrooms.

This two-fold architectural experiment, exterior and interior, fulfilled Jefferson’s aspiration to create a “visual narrative” through architecture and “to establish a universal standard of design and style emblematic of American, and more specifically Jeffersonian, democratic principles,”28 says historian Robert M. S. McDonald. However, Jefferson’s courtroom designs in the early 19th century simply repeated the arrangement of fittings that had evolved in colonial Virginia 50 to 75 years earlier. The only change was the use of a faceted bench as opposed to a curvilinear one.29 In one of Jefferson’s blueprints,30 dotted lines mark the magistrates’ seating area above the polygonal bench, and dotted lines directly under the bench mark “the narrower unpaneled bench reserved for the occasional sitting of petit juries.”31 The second image32 shows a similar layout but with a curvilinear bench instead of the polygonal bench.

JEFFERSON’S COURTROOM PLANS.

As in modern courts, legal authority rested with the judge’s bench, but the centralized location and close proximity of the jury bench demonstrated the power of the people in the exercise of local justice.33 Lounsbury writes that “the seated jurors were treated in the same deferential manner accorded the magistrates, confirming the notion that the jury was a respected part of the judicial system.”34 Courtroom etiquette added to this revered position of the jury, since standing tended to indicate deference, and lawyers stood to address the seated bench.35 Jefferson believed in the “majority” and “the will of the people.”36 To him, the future of democracy relied on these cornerstones. True to Jefferson’s belief, the VRM reflects Virginia’s continued practice of placing the people — the “majority” — at the center of the deliberation.

We see in the blueprints, and in elements of Cooke’s painting, that the centralized jury seated under the magistrates’ bench routinely characterized traditional Virginia courtrooms. Because Jefferson’s blueprint survives, the courtroom design has been attributed to his architectural genius. In the end, Jefferson set the standard for new courthouse design in the Commonwealth, but not by introducing new courtroom fittings. Rather, he simply applied what had been a standard arrangement.37 For Jefferson, architecture was yet another form of Enlightenment rhetoric.38 Believing “democratic legitimacy [turned] on the inclusion and participation of the community,” Jefferson portrayed through architecture “humanity’s right of self-governance.”39 What better way to solidify this pillar of American democracy than to incorporate architecturally and visually the jury’s shared authority with the magistrate judges?

Virginians embraced this concept, and, one after another, county commissioners implemented Jefferson’s model when building new courthouses.40 Although blueprints and other designs were largely destroyed in the violence and turmoil of the Civil War, many colonial era Virginia County courthouses exist today, bearing the unique design features of that colonial period, including the center-positioned jury bench. This is what we call the VRM courtroom.

Judicial Philosophy Animating the VRM

“[T]he space in which justice is done shapes what we think it means,”41 writes Professor Spaulding. The adversarial space of a courtroom — or rather, the space of justice — is a “dynamic space.”42 The VRM navigates this dynamic, living space with infrastructure that reinforces the foundation of American liberty and democracy. Symbolism matters, and, as architect KenzŌ Tange once said, “that means the architecture must have something that appeals to the human heart.”43 Tapping into the symbolic significance of the architecture, judicial philosophy provides a third strand of support for the VRM, even apart from the architectural approach and historical design.

The jury and witness have completely different experiences if the jury is sitting in the traditional, peripheral placement. In the VRM, the jury is not placed on the sideline of the adversarial space of a trial. Instead, the jury is in the center of the activity, and the intimacy of the VRM cannot be denied. The photos of the Charlotte courtroom showcase this intimacy with a view from the jury box to the witness stand only a few feet away.

The witness faces the jury, and serendipitously the judge, such that the jurors are now sitting in between the witness and judge, face-to-face with the witness, rather than off to the side eavesdropping on the conversation between the lawyer and witness. The jury is integral to the conversation, and the conversation is for their benefit. In this sense, the VRM assists the jury in its fact-finding task in “the space in which the passionate, messy, and indeterminate elements of public trial” take place.44 The organization of this space celebrates that justice “is not a set of fixed principles to be applied, but a set of relations to be mediated.”45 This reflects the magnificent dynamism of jury trials. Things come alive in the courtroom. Witnesses balk, hedge and dodge . . . or not. Lawyers hesitate before asking perhaps one question too many. There is an inchoate tension at play as society’s drama plays out one case at a time. In the VRM, the jury is no longer cast off to the side. But rather, the jury’s center-stage positioning accentuates its starring and decisive role in the courtroom drama.

Ultimately, the “fittings,” or organizational configurations, of the courtroom matter. They symbolize and reflect “the source of the courtroom authority.”46 When members of the public come to court, they should find that the layout confirms the hierarchical nature of power inherent in American democracy, as seen in the Rockbridge County Courthouse image below. As the Preamble to the Constitution communicates in its first three words, the American people are at the center of our nation, and their central placement in the courtroom reflects and communicates this foundational belief and spirit: “We the people . . . .”

ROCKBRIDGE COUNTY COURTHOUSE

Effect of the VRM

What could a centuries-old courtroom design offer a 21st-century justice system? A lot, it turns out. It is in fact a better design in which to try cases in the modern era. Let us see why.

Structural Representation

Structurally, the VRM reflects the true nature of the jury’s function and status within the American justice system. It is axiomatic that juries are the “judges” of the facts, and the jury shares authority with the presiding judge who has the duty of ensuring that the trial comports with evidentiary and legal principles. The judge instructs the jurors on this principle from the moment they walk into a courtroom until the end of the case when they begin deliberations. Thus, why should the centrality of the jury not be emphasized in the architectural design? The VRM communicates this principle by seating the jury in the center of the well, underneath the judge. Positioning the jury in this way not only educates jurors about the weight of their role and responsibility in the proceedings, but also empowers them to fulfill the often difficult task of fact-finding.

While emphasizing the jurors’ role, this empowerment also feeds each juror’s sense of self-efficacy in making findings of fact. Cornell Law Professor Valerie Hans writes, “Across countries, citizens who participate in juries or other forms of lay-participation systems become more positive about the use of lay legal decision-making and about the legal system.”47 When they are seated at the center of the adversarial space, jurors are more likely to feel like an important participant in the legal decision-making. Their voice makes a difference. Accordingly, it behooves us to shape our buildings in a manner that facilitates jurors’ investment in the legal system and a sense of responsibility for its outcomes.

Intimacy of Interaction

This important positioning is not merely symbolic. Placing the jury box in the center of the well, beneath the judge, increases the intimacy of the interaction between the jury and the witness. The jury finds itself in the middle of the action. The witness sits in the box in front of the jury, testifying directly to the jury. The lawyers question from the sides of the jury box, to the left or right depending on whether they are attorneys for the plaintiff or defendant. The lawyer is not at center stage, as is the case when the jury sits off to the side. In the VRM, the jurors find themselves in the middle of the conversation, in the search for justice.

THE VIEW FROM THE BENCH: THIS PHOTO FROM THE NEW COURTHOUSE IN CHARLOTTE, N.C., SHOWS THE VIEW FROM THE JUDGE’S PERSPECTIVE IN A VRM COURTROOM. (PHOTO COURTESY JENKINS PEER ARCHITECTS)

Within the VRM, this triangular field of focus possesses a level of intimacy and intensity not duplicated in the traditional model, as confirmed by the lawyers and judges who have practiced in both VRM and traditional courtrooms. In informal conversations with scores of lawyers and judges who have tried or presided over cases in both traditional and VRM courtrooms, we heard that the VRM courtroom is superior because the design fosters intimacy and intensity. The importance of this design feature is difficult to overstate. The authors contend that jury trials with direct- and cross-examination are our justice system’s best vehicle for the ascertainment of truth. Positioning the jury in the center enables them to observe what is important, giving the fact-finder the best view to observe testimony, demeanor, and body language. Facing the witness directly opposite the jury ought to encourage veracity and ensure the jury’s focus remains centered on the witness. This intimacy also should enhance credibility determinations and champion the jury’s truth-finding purpose — the raison d’être for the jury.

Improved Judge’s View

What is true for the jury is also true for the judge. She sits behind the jury in the VRM and consequently is in a better position to observe the witness directly. Similarly, the traditional courtroom handicaps the judge in much the same manner as the jury. The judge observes the witness sideways, often over a monitor or law book. It is a difficult angle and much is concealed from the judge. The awkwardness arising from the judge’s gaze towards the witness, which lands also on the jurors at the end of the jury box, compounds this inferior angle. The judge’s gaze often makes individual jurors uncomfortable. In the VRM, the witness faces the judge and jury directly, eliminating the judge’s side angle view. With this bird’s eye view of the witness, the judge can observe directly the witness’s tone, demeanor, and body language. These VRM dynamics very well may encourage witness veracity or at least discourage the impulse to lie.

Jury Less Affected by Judge’s Reactions

In addition to the judge being ideally positioned to observe the witness, she is able to do so in a way that does not influence the jury. Within the four corners of a courtroom, jurors tend to trust the judge above all others, and, at best, they feel a sense of security under her instruction. While this trust in the bench is something to revere and protect, it muddies the sanctity of the fact-finding process. It risks jurors basing their impressions and decisions on how they perceive the judge’s reaction to the testimony. The VRM protects the justice system from this Achilles heel. Sitting behind and above the jurors, the judge’s visible reactions to either witnesses or lawyers do not affect the jury or influence them in their fact-finding mission. The jurors reach their own conclusions, as opposed to following the judge’s nonverbal lead.

Furthermore, the jury is saved from the tennis match effect of the traditional courtrooms, in which jurors are constantly moving their gaze back and forth between the witness and counsel. In the VRM, the jury tends to look in only one direction: at the witness.

THE VIEW FROM THE WITNESS STAND: THIS PHOTO, ALSO FROM THE NEW COURTHOUSE IN CHARLOTTE, N.C., SHOWS THE VIEW FROM THE WITNESS STAND IN A VRM COURTROOM. (PHOTO COURTESY JENKINS PEER ARCHITECTS)

Egalitarian Effect

The VRM equalizes the playing field between lawyers by removing the typical advantage experienced by lawyers sitting closest to the jury box in the traditional courtroom. The traditional layout gives the positional advantage and the prime lawyer’s table to the party with the burden of proof.48 Generally, the party with the burden of proof gets to sit at the counsel table nearest the jury. But why should that be? Consider cases involving counterclaims where different parties have the burden of proof depending on which cause of action is being considered: Who sits where? What about matters in which the burden of proof shifts? The VRM neutralizes the burden of proof advantage. Instead, neither side holds an advantage. The parties face off on equal ground.

Each Juror Strategically Centered

The VRM wins on individual jury placement logistics as well. One of the most difficult design goals to achieve in modern courtroom construction is a jury box accommodating 12 jurors, plus alternates. The U.S. Courts Design Guide, which sets the standards for federal courthouse construction and design, envisions space for four alternates: 16 total chairs. The side jury box, built to the left or right of the judge’s bench, consists typically of two-to-three rows of six-to-eight juror seats per row. Giving each juror adequate space results in the jurors at the far end of the box having a completely different experience than jurors sitting nearest to the witness. This “football field” effect is difficult to design away in the traditional model.49 The jurors farthest from the witness and the judge experience the trial entirely differently from the juror in the seat closest to the witness and judge. This disparity simply does not exist in the VRM. Each juror is in the central area of action in the triangle of proximity between the counsel tables, witness stand, and judge.

Logistical Difficulties

The authors contend that the substantive and symbolic factors weigh heavily in favor of the VRM, while recognizing that some procedural difficulties must be considered. Because the traditional model has been in use for centuries, parties and lawyers have adopted procedural approaches that best fit that design concept. Some of those procedures would have to be rethought in the VRM context.

For example, some parts of a jury trial, such as jury selection and charging the jury, may seem more easily accommodated in a traditionally designed courtroom, where the judge faces the jury box on the side of the courtroom. But there is a VRM design solution to this problem: Juror seats may be designed to swivel to face the judge during voir dire and jury instruction. Or the judge can come off the bench and conduct voir dire or instruct the jury from a table podium placed on the witness stand in the center of the well.50 Moreover, those portions of the trial are limited to the beginning and end of the proceedings, whereas the central purpose of a trial — the discovery of the truth through adversarial testing — is better served where witnesses testify face-to-face with jurors.

Additionally, sidebars would have to be rethought, since the traditional design concept facilitates them on the side opposite the jury box. In the Albemarle County Courthouse, the judge’s chambers are located to the side of the judge’s bench, and that space perfectly accommodates side bar conferences. Other less-than-optimal options include the judge stepping down and approaching counsel tables, or, when necessary, the jury can withdraw to the jury room. At the end of the day, the provision of an auxiliary room off to one side of the judge’s bench, whether it be the judge’s chambers, a robing room, or simply an office space, would be ideal, especially given that robing rooms are a staple design component of most modern courtrooms.

The location of the court reporter is another variable, but options exist. In the Albemarle County Courthouse, the court reporter sits next to the judge, whereas in the City of Charlottesville Courthouse, the court reporter sits next to the witness stand. The determined location will vary according to space and acoustics, as well as local preference.

Yet another element for consideration are courthouse security measures. The Court Security Division (CSD) at the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) evaluated the VRM from a security perspective.51 The CSD conducted a site visit to the VRM at the Rockbridge County Courthouse in Lexington, Virginia, and interviewed two Rockbridge County Sheriff’s Department deputies. These interviews assured the CSD that its evaluation would be based on direct input from security professionals performing security duties in both traditional and VRM courtrooms. The CSD also performed a conclusive assessment of the VRM blueprint. Ultimately, the consensus following the assessment, visit, and interviews was that no changes to security would be necessary, and, even more auspiciously, that the VRM would facilitate improved security measures.

The judge’s positioning would require no change in security systems or security equipment. In fact, the judge would have a better view of the gallery throughout the entire proceeding and would be better positioned to observe any efforts from the gallery to induce jury or witness intimidation. Additionally, and perhaps most notably, the judge would be farther away from an in-custody witness, who, in a traditional courtroom, is positioned in close proximity to the judge with nothing but a railing separating them. With the VRM, the jury would be seated closer to the judge and would be easier to protect because the witness would not be seated between the judge and jury.

In a criminal trial, the defendant would require no change in seating nor in entering and exiting procedures. The defendant would be seated in the center of the defense counsel table. From that position, the defendant would not be able to make direct eye contact with the witness while testifying. This change in the direct line of sight between the witness and defendant should significantly lessen the threat of witness intimidation during examination. Potential witness intimidation from the gallery is also decreased because the witness is facing the judge, not the gallery.

Ultimately, just as the trial-and-error method led to the development of procedural fixes for the traditional courtroom, use of the VRM will resolve these difficulties over time. In any event, the substantive improvements the VRM stands to bring to the ascertainment of truth far outweigh these procedural hurdles. Truth-finding is the paramount goal of a jury trial, and the VRM best facilitates this endeavor.

Conclusion

As the “judge” of the facts, the jury navigates the dynamic reality of a jury trial, separates the wheat from the chaff on the scales of justice, and issues its decision. This is not a job for a sideline factfinder — it is the job for one at the center of the action. Courtroom design should reflect the magnitude of this authority and responsibility.

The organization of the space where justice is exercised shapes how justice is done.52 Consequently, courtroom design plays an integral role in dispute resolution, the quest for truth, and the administration of justice. The VRM creates a physical space that reflects the principles of American democracy by placing the jury at the center of the trial dynamics, not off to the side as a bystander.53 The people are engaged, and democracy is celebrated. At the center, the jury has an impact, affecting the witness as he testifies under the pressure of the jury’s truth-seeking scrutiny. Further, the VRM removes the judge from the jurors’ views so that jurors cannot follow her lead or allow her reactions to affect outcomes — ultimately protecting the sanctity of the jury’s decision.

Thus, supporting our position with the research and beliefs stated in this essay, we stand by our thesis that present-day needs, historical design, and philosophical considerations support this “innovation by recapture” of the VRM. Exercising intentionality and vision, we must embrace and value the opportunities we are given to shape our buildings — the infrastructure of justice and the pillars of our judicial history — so that they might better serve their purpose going forward and shape the course of justice in our American democracy.

Footnotes:

- Norman Spaulding, The Enclosure of Justice: Courthouse Architecture, Due Process, and the Dead Metaphor of Trial, 24 Yale J. L. & Human. 311, 311–43 (2013) (quoting Winston Churchill, speaking before the British House of Commons in 1943 on the question of how the House building should be rebuilt after its destruction in German air attacks on London).

- Id. at 311.

- “Great Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and more than 40 other nations employ juries of citizens drawn from the general population who decide cases collectively. Many countries that were once part of the British Empire inherited the English legal system, including its jury.” Valerie P. Hans, Jury Systems Around the World, 4 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 275, 278 (2008); see also The Jury Is Out, The Economist(Feb. 12, 2009), http://www.economist.com/node/13109647.

- Hans, supra note 3, at 280.

- See, e.g., John R. Grisham, The LastJuror(2004); John R. Grisham, The RunawayJury(1996); Leon M. Uris, QB VII (1970); ACivil Action (Touchstone Pictures 1998); MyCousin Vinny(Twentieth Century Fox 1992); Presumed Innocent(Warner Brothers 1990); The Rainmaker(Constellation Ent. 1997); ATime to Kill (New Regency Productions 1996); The Good Wife (CBS television broadcast 2009–2016); Matlock (NBC & ABC television broadcast 1986–1995).

- See generally, Robert J. Conrad & Katy L. Clements, The Vanishing Criminal Jury Trial: From Trial Judges to Sentencing Judges, 86 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 99 (2018) (discussing the decline of federal criminal jury trials throughout the 21st century).

- The Jury Is Out, supra note 3 (quoting the late Lord Devlin, a British law lord).

- Spaulding, supra note 1, at 340, 343.

- Linda Mulcahy, Legal Architecture: Justice, Due Process, and the Place of Law 2 (2011).

- Id. at 2.

- Id. at 3.

- Id. at 1.

- Id.

- Omnibus Appropriations Bill, H.R. 2029, 114th Cong. (2016).

- The apt terminology used by architectural historian Carl Lounsbury. See Carl R. Lounsbury, The Courthousesof EarlyVirginia: An Architectural History(2005).

- Judicial Conference of the United States, U.S. CourtsDesign Guide (2007), https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/Courts_Design_Guide_07.pdf.

- Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 (2018).

- See American Artifacts: Colonial Williamsburg Courthouse, C-SPAN (Oct. 14, 2015), https://www.c-span.org/video/?401529-16/colonial-williamsburg-courthouse.

- Patrick Henry Arguing the Parsons’ Cause, Virginia Museum of History& Culture, https://virginiahistory.org/learn/patrick-henry-arguing-parsons-cause (last visited Sept. 7, 2021).

- RobertM. S. McDonald, Lightand Liberty: ThomasJefferson and the Powerof Knowledge 176 (2012). The painting captures one of Patrick Henry’s famous orations at the Hanover County Courthouse. The legal, political dispute at issue in the painting is “Parson’s Cause,” which arose out of colonial conflict over the Two Penny Act, passed by the Virginia colonial legislature in 1758. At that time, Virginia’s Anglican clergy collected an annual tax of 16,000 pounds of tobacco, and they maintained this amount following a poor harvest that caused the price of tobacco to rise from two to six pennies per pound. The rise in price inflated clerical salaries, so the House of Burgesses responded by passing the Two Penny Act, which allowed tobacco debts to be paid in currency at a rate of two pennies per pound. King George III quickly vetoed the legislation, sowing resentment and animosity in the colonies. Following the king’s veto, a reverend in the clergy brought a claim in Hanover County court to collect unpaid taxes. Patrick Henry defended the county against the reverend’s claims and argued in favor of the Two Penny Act. In the end, the jury awarded the reverend one penny in damages, and the award essentially nullified the Crown veto. No other clergy sued. Folklore suggests that the victorious attorney, Patrick Henry, was carried on the shoulders of his clients to the tavern next-door, through the open door depicted in the painting on page 57.

- Lounsbury, supra note 15, at 152.

- Id.; painting info from Virginia Historical Society.

- Lounsbury, supra note 15, at 151–52.

- Id. at 137.

- Id. at 91.When Robert Beverley published his history of Virginia in 1705, no more than three or four of the 25 counties in existence could boast a brick courthouse. In the second quarter of the 18th century, many courts began to replace their second or third wooden buildings with larger and more imposing brick structures. By the time of the Revolution, this process had been nearly completed in the older established tidewater counties but had scarcely begun in the newer counties to the west. In 1776 slightly more than half the 60 counties had brick courthouses.Id.

- Id. at 91 (quoting Thomas Jefferson, Noteson the State of Virginia 154 (William Peden ed., W.W. Norton & Co. 1982)).

- Id. at 92.

- McDonald, supra note 20, at 159.

- Telephone Interview with Carl Lounsbury, Historian (July 25, 2017).

- The Architecture of Thomas Jefferson: Jefferson’s Courthouse Plan, The Institute forAdvanced Technologyin the Humanities, http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/wilson/cgi-bin/draw_filter.pl?id=N023 (last visited Oct. 5, 2021); see also Projects, The Institute forAdvanced Technologyin the Humanities, http://www.iath.virginia.edu/projects.html (last visited Oct. 5, 2021) (describing the Institute’s projects).

- Id. at 151 (citing Plan, Amelia County courthouse, 1791 (Deed Book, 1789–91, Clerk’s Office, Amelia County)).

- Lounsbury, supra note 15, at 153.

- Id. at 151.

- Id.

- Id.

- Jeffersonian Ideology, Jeffersonian America: A Second Revolution?, U.S. History, http://www.ushistory.org/us/20b.asp.

- Telephone Interview with Carl Lounsbury, Historian (July 25, 2017).

- McDonald, supra note 20, at 159.

- Spaulding, supra note 1, at 159.

- McDonald, supra note 20, at 180.

- Spaulding, supra note 1, at 340, 343.

- Id.

- Kenzo Tange (1913–2005), winner of the 1987 Pritzker Architecture Prize, is one of Japan’s most honored architects. Biography, PritzkerArchitecture Prize, http://www.pritzkerprize.com/1987/bio, (last visited Oct. 5, 2021) (“[H]e is revered not only for his own work but also for his influence on younger architects.”).

- Spaulding, supra note 1, at 318.

- Id. at 341.

- Lounsbury, supra note 15, at 162.

- Hans, supra note 3, at 284.

- In the Western District of North Carolina, the party with the burden of proof sits closest to the jury. In some other districts, on the other hand, it is a free-for-all; whoever gets to the courthouse first the morning of trial gets to sit closest to the jury.

- Carrie Johnson, Why Courts use Anonymous Juries, Like in Freddie Gray Case, Nevada Public Radio (Nov. 30, 2015), https://knpr.org/npr/2015-11/why-courts-use-anonymous-juries-freddie-gray-case.

- Even better, say most lawyers to federal judges, let us do the voir dire!

- E-mail from Victor Jones to author (Oct. 6, 2017, 16:33 EST) (on file with author).

- Spaulding, supra note 1, at 340, 343.

- The Jury Is Out, supra note 3 (quoting the late Lord Devlin, a British law lord).