by Kyle C. Kopko and Erin Krause

Vol. 99 No. 2 (2015) | The Mass-Tort MDL Vortex | Download PDF Version of Article

On March 28, 1996, Justices David Souter and Anthony Kennedy testified before a House Appropriations subcommittee to discuss the Supreme Court’s budget for the upcoming fiscal year. Souter, appointed by President George H.W. Bush, was known as a soft-spoken justice who typically kept out of the limelight. When he and Justice Kennedy were asked of the possibility of televising U.S. Supreme Court proceedings, Souter responded uncharacteristically: “I can tell you the day you see a camera come into our courtroom, it’s going to roll over my dead body.”1

Justice Kennedy agreed that introducing cameras into the nation’s highest court was a bad idea. In justifying their responses, Justice Souter claimed that when he was a judge in New Hampshire, he altered his behavior when a camera was in the courtroom out of fear that his comments would be taken out of context. Justice Kennedy explained that by excluding cameras from the Supreme Court, the Justices signaled to the public that the Court was fundamentally different from the other political branches of government. Ten years later, Justice Kennedy, along with Justice Clarence Thomas, reaffirmed this position when testifying before the House Appropriations subcommittee on transportation, treasury, judiciary, and housing and urban development, which handles the Court’s budget.2

There have been efforts to introduce cameras into the U.S. Supreme Court by members of the press since at least the 1970s,3 and on numerous occasions Congress has tried to pass legislation permitting cameras in the Supreme Court.4 At the start of the 114th Congress, at least one pending bill proposed introducing cameras in the high court.5 So far, all of these efforts have failed. However, the fact that members of Congress still introduce legislation on this topic, and that prominent legal scholars and practitioners have argued for cameras in the Court,6 demonstrates a continuing demand by some individuals for visual access to Supreme Court proceedings.

Recently, and despite restrictions on cameras in the Supreme Court, the public received its first video glimpse of the Court in session. A group named 99Rise — an organization affiliated with the Occupy movement — smuggled a hidden video camera into the Supreme Court on at least three different occasions.7 They did so first on Oct. 8, 2013, to film part of the oral arguments in McCutcheon v. FEC,8 and then again on Feb. 26, 2014, during the oral arguments of Octane Fitness v. Icon Health & Fitness.9 Segments of these two sessions were combined into one video clip. This video depicts part of the McCutcheon oral argument, and then cuts to arguments in Octane Fitness, when a 99Rise protester, Kai Newkirk, interrupts the proceedings to denounce the Court’s decision in Citizens United v. FEC.10 Nearly a year later, on Jan. 21, 2015 — the fifth anniversary of the Citizens United decision — seven members of 99Rise interrupted the start of the Court’s session to, once again, protest the Citizens United decision. This most recent disruption was captured by hidden camera, but viewers could not see any Justices in the video frame; the video depicts the Supreme Court chamber and Chief Justice John Robert’s voice is audible.11 In each instance, the demonstrators were promptly removed from the Supreme Court chamber by Supreme Court police and charged with various criminal offenses, including violating 40 U.S.C. § 6134 for “mak[ing] a harangue or oration, or utter[ing] loud, threatening, or abusive language in the Supreme Court Building or grounds.”12

While these security breaches represent the first time that a session of the Supreme Court was recorded with a video camera, it was not the first time an observer smuggled a camera into the high court to document the justices in action. Scholars have usually acknowledged that there are one13 or two14 photographs of the Supreme Court in session. There are, however, at least three known photographs in existence, in addition to the videos captured by 99Rise. Our purpose here is to discuss how these three images of the Court — all taken in the 1930s — came into existence and discuss a potential explanation as to why cameras were originally banned from the Supreme Court. This article also represents the first time all three images are published together. As we detail in the following sections, the history of these images is unique, and each image provides a rare glimpse inside the most secretive branch of government.

A former chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Horace Gray took his seat on the U.S. Supreme Court in 1882 and served on the bench for 20 years. During his tenure, Gray wrote several notable opinions that contributed to the Court’s body of constitutional jurisprudence — including majority opinions that upheld the use of paper money in peacetime,15 struck down unapportioned income taxes implemented by the Income Tax Act of 1894,16 and interpreted the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,17 among many other cases.

Perhaps Justice Gray’s most important institutional contribution was the introduction of law clerks at the Supreme Court. In Massachusetts, Gray had hired clerks to assist him in carrying out his judicial duties, and he continued to do so when appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. While early law clerks primarily completed clerical tasks on behalf of their justice, Gray’s clerks took a more expansive role. Scholars have noted, “Gray was the first [Supreme Court justice] to request that his clerks draft opinions for cases, although the drafts were only used to stimulate Gray’s own writing. Gray also debated his clerks regarding the cases before the Court, and expected the clerks to defend their views.”18 The role of Gray’s law clerks, in many ways, resembles the duties of modern clerks at the Supreme Court, and therefore constitutes an important contribution to the internal operations of the Supreme Court. But, according to a news account from the late 1800s, Justice Gray was also responsible for another important institutional contribution to the U.S. Supreme Court — the Court’s ban on photography and cameras.

Previous research indicates that the judiciary has resisted cameras in the courtroom since 1937, when the American Bar Association adopted Canon 35.19 However, there is evidence to suggest that a ban on cameras in the Supreme Court occurred years earlier. On Nov. 17, 1895, the newspaper The Sun printed an article titled The Supreme Court Bars Kodaks: A Snap Shot Taken at Justice Gray While he was Dozing on the Bench.20 Here is the full text:

“Visitors and tourists to Washington are not allowed to take kodaks into the Supreme Court room. It is said that the dignified members of that high judicial tribunal were deeply mortified recently by the report that a kodak fiend took a snap shot at Mr. Associate Justice Horace Gray of Massachusetts while he was “dozing” on the bench. Judges of the Supreme Court frequently take “forty winks” during the arguments if the talk happens to be uninteresting but they manage to conceal the fact from all but the closest observers. Justice Gray is the tallest member of the court and for that reason he is, the most conspicuous; besides he has a peculiarly shaped head, which always attracts attention and elicits comment from visitors.

Unfortunately for Mr. Justice Gray he is more given to “nodding on the bench” than any of his associates, and when he takes a nap his head falls low upon his breast, his mouth hangs open, and he could not truthfully be called a “sleeping beauty.” It was during one of his naps that the kodak fiend got in his work. Naturally Mr. Justice Gray is very sensitive on the subject, and he was further mortified one day by receiving a severe reprimand from his wife. She had taken some friends to the capitol to witness the proceedings of the court, but principally to show off her husband in his rich silk gown. It so happened that the case pending before the court was dull and the attorneys uninteresting, so that when Mrs. Gray and her friends entered the courtroom Judge Gray was sound asleep in his chair.”21

While it is difficult to say if these events took place in the manner the unnamed author describes — and it is important to note that such a photograph has never publicly surfaced — this unflattering account was nonetheless reprinted in a number of newspapers throughout the United States.22 If accurate, this article suggests that the ban on cameras in the Supreme Court occurred in reaction to an embarrassing situation; it may have been intended as a means of protecting the justices from similar circumstances in the future. This stands in contrast to the reasons that contemporary justices of the Supreme Court cite to justify a ban on video cameras — specifically, the justices might be forced to change their behavior out of fear that their comments will be taken out of context.23

Regardless, this story is the first reported instance where the Supreme Court suspected that a session of oral arguments had been photographed, and the Court then took action to ensure that the event would not repeat itself. But more than 30 years later, three other observers would smuggle a camera into the Court’s chamber during oral arguments. This time, however, the images would be made public.

The first and only publicly identified person to take a still photograph of the Supreme Court in session was the celebrated German photojournalist, Erich Salomon. Salomon earned a doctorate in law from the University of Munich in 1913 and shortly thereafter was drafted into the German armed forces during World War I. While fighting during the war, he was captured and spent several years in a French prisoner-of-war camp. In the mid-1920s, following his release, Salomon secured a job with a periodical publishing company and began to experiment with photography. “His big break came in 1928 when he snuck his small glass plate Ermanox camera into several high-profile criminal trials, and the pictures were published internationally.”24 This was just the first of many clandestine photo shoots by Salomon, who also snapped shots of diplomatic meetings in The Hague and sessions of the League of Nations.25 Although Salomon would fall victim to the Nazis — he lost his life in 1944 when imprisoned in the Auschwitz concentration camp — his photographs still received international acclaim decades after his death.

Salomon made a name for himself throughout Europe. He captured images of government officials in unscripted moments, where they clearly were not posing for the camera. Salomon’s work was described as “candid” photography, or that he used a “candid camera.” Those labels still apply to this genre of photography today,26 as do Salomon’s tactics:

He typically waited for a gesture, like a yawn or the lighting of a cigarette, before using a cable release to trigger his camera’s shutter. The method enabled him to capture something wholly human in Europe’s elite . . . [Salomon] was expert at evading security, and he snuck his camera into numerous social and political functions using hats, diplomatic pouches, even an arm sling to disguise his gear.27

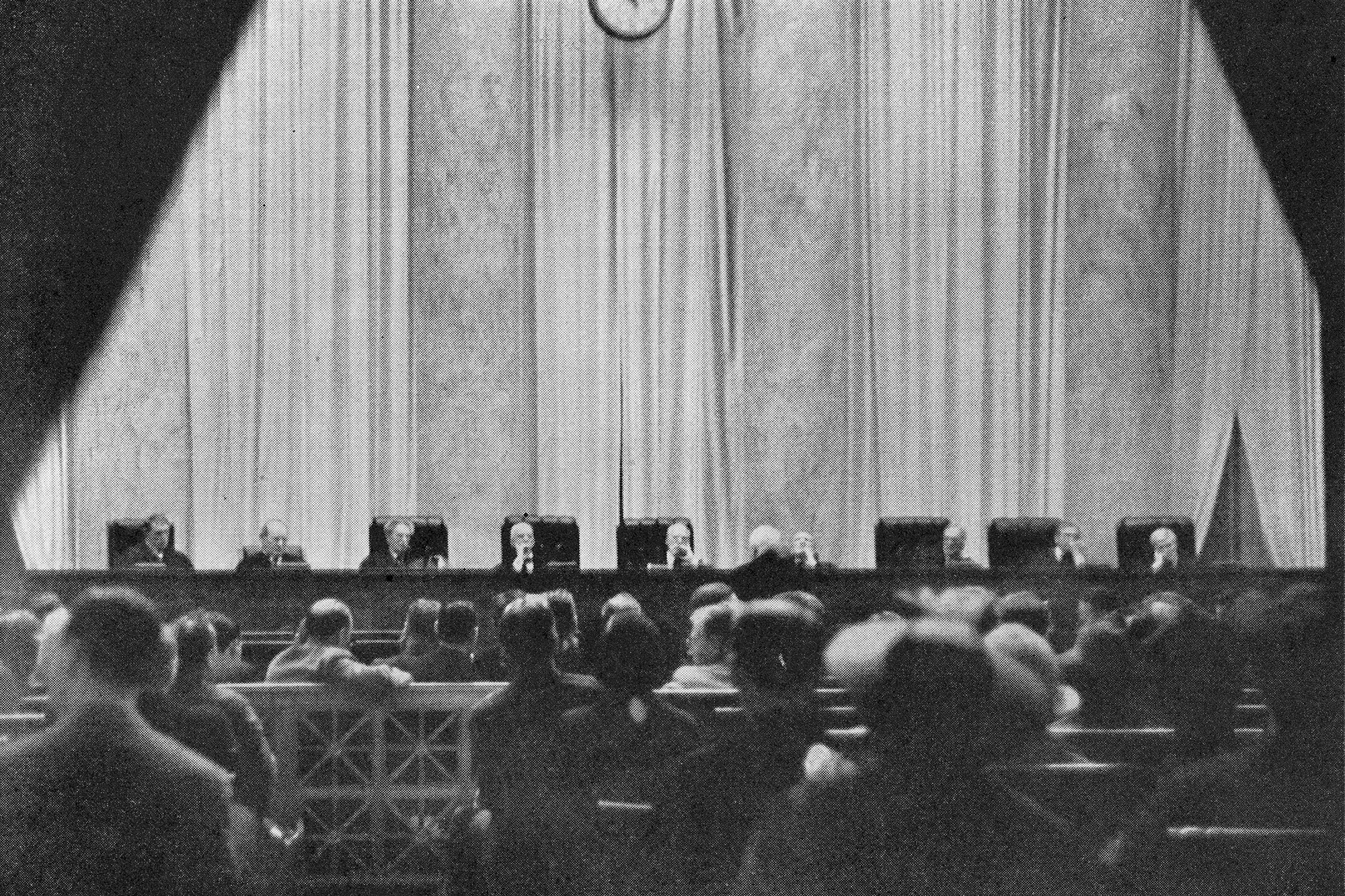

In fact, it was an arm sling that facilitated the first publicly published photographs of the Supreme Court in session; Salomon faked a broken arm to conceal the camera when he visited the Court in 1932.28 Salomon’s photographs of the Court appeared in the October 1932 edition of Fortune magazine, in an article titled The Supreme Court Sits. At the time, the Supreme Court met in the Old Senate Chamber within the U.S. Capitol Building; the current Supreme Court building would not open until 1935. The Fortune article included three photographs taken by Salomon. One photograph depicts eight members of the Court hearing arguments in the spring of 1932 — Justice James C. McReynolds was absent during this session of the Court.29 The second photograph in the article depicts a decorative eagle and clock located above the bench, while the third photograph is a blurry depiction of the full Court. The Fortune article described the work of the justices and their routines as they prepared for oral arguments. The article also praises the justices for their hard work in the October term of 1931: “for the first time in years, the Justices have been getting through the docket in record time — 884 cases disposed of last year, with cases reached in six weeks instead of two years.”30

Apparently, members of the Court were not pleased with the publication of these images. An undated newspaper clipping obtained from the Supreme Court Curator’s Office, titled Court Bars Cameras, was printed sometime after the release of the Fortune magazine article. The article reports that in reaction to these photographs, the Supreme Court issued a ban on cameras. Here is the full text of the article:

“As a result of the publication of a photograph of the court on the bench, taken with a concealed camera, an official ban was ordered yesterday on all interior pictures of the Supreme Court in session.

The photographer who took the picture causing the ban, after he had been refused permission to photograph the court, will be denied further admission to the court.”31

Although very brief, this news article provides important historic information about the ban on cameras in the Supreme Court. First, this article claims that the photographer (i.e., Erich Salomon) requested permission to photograph the Court, his request was denied, but he did so regardless. As such, he was barred from future entrance to the Court. Second, this article also claims that the Supreme Court issued an official ban on cameras. While there is no reason to doubt this account, it is curious that such an action was warranted given that earlier news reports indicate that the Court barred photographs in the late-19th century. This suggests that the news story of Justice Gray sleeping on the bench may have been fabricated, or perhaps members of the Court in 1932 did not realize that a ban was implemented 37 years earlier. Unfortunately, it is impossible to say with certainty which account is true given the limited historic record that has survived. Nonetheless, it is the case that Salomon was the first person to provide the public with an insider’s view of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The second photograph of the Supreme Court to publicly surface was printed in the June 7, 1937, edition of Time magazine, in an article titled Judiciary: Farewell Appearance.32 The article discussed the close of the Court’s historic 1936 term — in which Justice Owen Roberts voted with liberal justices to uphold key New Deal policies — and Justice Willis Van Devanter’s pending retirement. The article depicts the final day of the Court’s term and noted:

[The Justices] looked unusually cheerful and healthy. Even dour Justice McReynolds was smiling as if he had swallowed some kind of canary. But all eyes were on Justice Willis Van Devanter, whose retirement was to become effective next day. He came in pink cheeked, with a lovely stride, his gown open showing his white shirt front. As he took his seat, he nodded to one or two acquaintances below, then settled back chewing gum with undisguised contentment.33

This photograph was taken during an afternoon sitting of the Court in May of 1937. While Erich Salomon hid his camera in an arm sling to photograph the Court in 1932, this time a woman concealed a camera in her purse. In discussing the photograph, the article states:

How this famed Court appeared only a short time before its final session will be well preserved for history by the accompanying photograph. It is the second photograph ever taken of the Supreme Court in actual session, and the only one showing the Justices in their new chamber. The other, taken five years ago by Dr. Erich Salomon, made its first appearance in TIME Inc. publications as does this, taken last month by an enterprising amateur, a young woman who concealed her small camera in her handbag, cutting a hole through which the lens peeped, resembling an ornament. She practiced shooting from the hip, without using the camera’s finder, which was inside the purse, before achieving the result.34

In reaction to the Court’s ban on photography while in session, Time magazine did not identify the photographer by name. The only information known about the photographer appears in the previous quoted paragraph. This image is also the first time that all nine members of the Court were photographed in session. Following the publication of this article, just four months later, the third — and to date, final — still photograph of the Court in session was published in a news outlet.

To date, no article has identified the third and last-known still photograph of the Supreme Court to be publicly disseminated. On Tuesday, Oct. 5, 1937, New York’s Daily News featured a front-page story titled Black Takes Supreme Court Seat, by Dorris Fleeson.35 The image depicted the Court sitting for proceedings on the previous day — the start of the 1937 term. This, too, was the first time that Justice Hugo Black sat for a session of the Court. Undoubtedly, this was a tumultuous first day for the famed justice.

Just three days earlier, on Oct. 1, Justice Black delivered an unprecedented, nationally broadcast radio address to discuss allegations that he was an active member of the Ku Klux Klan (“KKK”).36 Although Black had been accused of being a member of the KKK when the U.S. Senate took up his nomination to the Supreme Court, Black had denied that he was currently a member. But a series of articles printed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in September of 1937 suggested that Black relied on KKK connections to gain a seat in the U.S. Senate and that he was still a member of the organization. These articles caused a sharp public outcry, and a Gallup poll reported that 59 percent of respondents believed that Black should resign his seat on the Supreme Court if he still was a member of the KKK.37 Under immense pressure from reporters — some of whom hounded Black and his wife as they vacationed in Europe before the start of the Court’s term — Black made his historic radio address. He admitted to once having been a member of the KKK, but he said that he had resigned his membership and denied that he was biased toward minority groups.38 While the speech did cause a swing in public opinion — a subsequent Gallup poll showed that 56 percent of respondents believed that he should remain on the Court — not everyone was pleased that Black, a staunch New Deal supporter, would soon begin service as a justice. Among those not pleased with Black’s new role as an associate justice included two members of the Supreme Court Bar — Patrick Henry Kelly and Albert Levitt.

As the Court session began on Oct. 4, Chief Justice Hughes admitted new members to the Supreme Court Bar. Kelly, an attorney from Boston, interrupted the proceedings on behalf of himself and Levitt, a former federal district judge for the U.S. Virgin Islands. The tactic and the subject of their motion was brazen and unfathomable by contemporary standards — they sought to block Justice Black from taking his seat on the Supreme Court — and their claim was novel and technical.

In the Act of March 1, 1937, Congress provided a pension for justices who retired at age 70.39 Justice Van Devanter took advantage of this retired status when he resigned from the Court in June of 1937. In Kelly and Levitt’s view, Justice Black could not serve on the Supreme Court because 1) Justice Van Deventer was still, technically, a member of the Court (albeit a “retired” justice) and therefore no vacancy existed for Black to fill, and 2) because the Act of March 1, 1937, resulted in an increase in emoluments with the creation of a judicial retirement pension, Black’s appointment violated the Emoluments Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 6, Clause 2).40 Under the latter argument, Black would be ineligible to accept a position on the Court at least until January of 1939, which coincided with the end of his term of office in the U.S. Senate.41

According to the Daily News article, when Kelly first interrupted the admission proceedings, Chief Justice Hughes “with his celebrated benignancy, said, ‘You are out of order.’”42 Once the admissions proceedings concluded, Kelly once again rose to address the Court. He began, “In a point of personal privilege as a member of this bar.” “Is your motion in writing?” the Chief Justice sternly replied. The Daily News article details what transpired next:

Kelly volubly began to explain it was not, but that he had written each Justice a letter. Hughes’ tone became acid and plain clothes officers moved up from the rear of the room ready for action.

“Please put the motion in writing and submit it,” Hughes said sharply. “Oral statements are not permitted on a motion of that character.”43

The motion was put in writing by Albert Levitt, and the Court ruled on the motion seven days later, on Oct. 11, in a per curiam decision.44 The Court dismissed the claim for lack of standing. In the Court’s determination:

The motion papers disclose no interest upon the part of the petitioner other than that of a citizen and a member of the bar of this Court. That is insufficient. It is an established principle that to entitle a private individual to invoke the judicial power to determine the validity of executive or legislative action he must show that he has sustained or is immediately in danger of sustaining a direct injury as the result of that action and it is not sufficient that he has merely a general interest common to all members of the public.45

This decision ended the controversy over Justice Black’s membership in the KKK, a most unusual series of events documented by the Daily News article and its accompanying photograph.

Unfortunately, the article does not provide any information about the photographer or the means by which the photograph was taken. However, it is virtually certain that the camera was concealed in a manner similar to the two previous photographs taken in the spring of 1932 and May of 1937. This would be the last time that a news outlet published a still photograph of the Supreme Court in session.

These three photographs provide a depiction of the U.S. Supreme Court from a bygone era. If anything, the images and their companion articles demonstrate that, historically, there has been a clear demand for greater visual access to the Supreme Court. Undoubtedly, these images were the only opportunity that many Americans had to see the Court in action. Even today, 78 years since the last still photograph of the Court in session was published, there is demand from members of Congress46 and interest groups47 for greater visual access to the Supreme Court. Given that justices continue to resist the call for cameras in the Court,48 the introduction of cameras in the Supreme Court will likely be a recurring debate among legislators, journalists, the public, and members of the Court for years to come.

Perhaps most surprising is the fact that more photographs of the Court in session have not appeared in the popular press between the publication of the Oct. 5, 1937, edition of the Daily News and the videos released by 99Rise in 2014. Despite the technological advancements that occurred during that time, there was, nonetheless, a photographic dry-spell that lasted for more than three-quarters of a century. With the recent video shot by 99Rise using a camera pen, it may be the case that the public can expect more of these images and videos to surface in the coming years. Certainly, increased security at the Supreme Court will make the possibility of these types of videos less likely to occur, but it remains to be seen if future security breaches will be prevented.

What the group 99Rise did in 2014 and 2015 was unique in that they interrupted the Court’s proceedings, and criminal charges were filed against these individuals as a result of their actions. But as the historical evidence indicates, their efforts to smuggle cameras into the Supreme Court were far from original. It may be the case that until, and if, the Supreme Court decides to televise its proceedings, there will always be the possibility of individuals trying to capture images of the Court conducting its business. In the meantime, short of visiting the Supreme Court in person, these images and videos are the only opportunities for most Americans to see what happens during a session of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Kyle C. Kopko is an Assistant Professor of Political Science, and Director of the Honors and Pre-Law Programs at Elizabethtown College.

Erin Krause is a candidate for a B.A. in Political Philosophy & Legal Studies and English Professional Writing at Elizabethtown College.

Footnotes: