Being Like Boehm: David Boehm

Select Articles (Pre-2015) | Volumes 1-98

Published February 2014

I first met Justice David Boehm in 1976 when I was a young associate at a firm in upstate New York. At the time, I was assisting a partner in a personal injury case that involved an accident between a car and a tractor trailer. In order to establish that the tractor trailer had caused the accident, we wanted to call an accident reconstruction expert to testify. I had prepared a memo for the court that tracked a then-recent trend of admitting the opinions of accident reconstruction experts. Judge Boehm, who presided over the trial, took our application in his chambers.

After listening intently to the arguments of counsel, Judge Boehm – in a soft and very dignified voice – told the partner and me that he had read our memo and was very interested in the cases on which we had relied. My partner, always a kind fellow, informed the judge that the memo was completely my work. In turn, Judge Boehm politely asked the partner if he could ask me a question. “Of course,” the partner replied, sensing perhaps that a favorable ruling was just around the corner. “Tell me, Mr. Wesley, did you read the briefs at the Appellate Division [New York’s intermediate appellate court] in the case on which you rely so heavily?” Completely dumbstruck, I had to confess that I had not.

Judge Boehm then proceeded to dictate his decision on the record, complete with citations and a careful review and explanation of why my most treasured case did not apply in our situation. We, of course, lost the motion. Nonetheless, Judge Boehm was courteous throughout the trial and never raised his voice or appeared annoyed with counsel. And although we lost the motion, he was instrumental in helping both sides settle the case.

From that trial on, Judge Boehm became in my mind the true measure of a good judge: doggedly thorough, courteous, and respectful of the process and its participants . . . a gentle scholar in a robe. In the years to come, before New York adopted an individual calendar system, I would time important motions in my cases to ensure they came before Judge Boehm. Each time, I pored over the motion papers and my memoranda of law to ensure that no important fact or legal consideration was omitted or overlooked. I knew my case would be carefully reviewed by the Judge and through my diligence . . . I won my share.

In 1986, I was elected to the New York Supreme Court, New York’s highest trial court. I was to be Judge Boehm’s colleague and immediately set a goal that I would “Be Like Boehm.” For the next seven years, I served as a trial judge in Supreme Court. Throughout these years, I did my best to emulate Judge Boehm – his attention to detail, thorough preparation, and interest in the parties’ dispute whether it was a straightforward contract matter or the occasional, and always treasured, intersection of competing legal principles in which the resolution had not yet been explored by New York’s appellate courts. I would often stop by his chambers to ask his opinion on a tough case or to seek out advice on how to handle a difficult matter. As was my experience before him as a practitioner, he was always gracious and always right on the mark. “Being Like Boehm” enriched my judge-life and made the company of lawyers a stimulating and meaningful experience. But then there was a change.

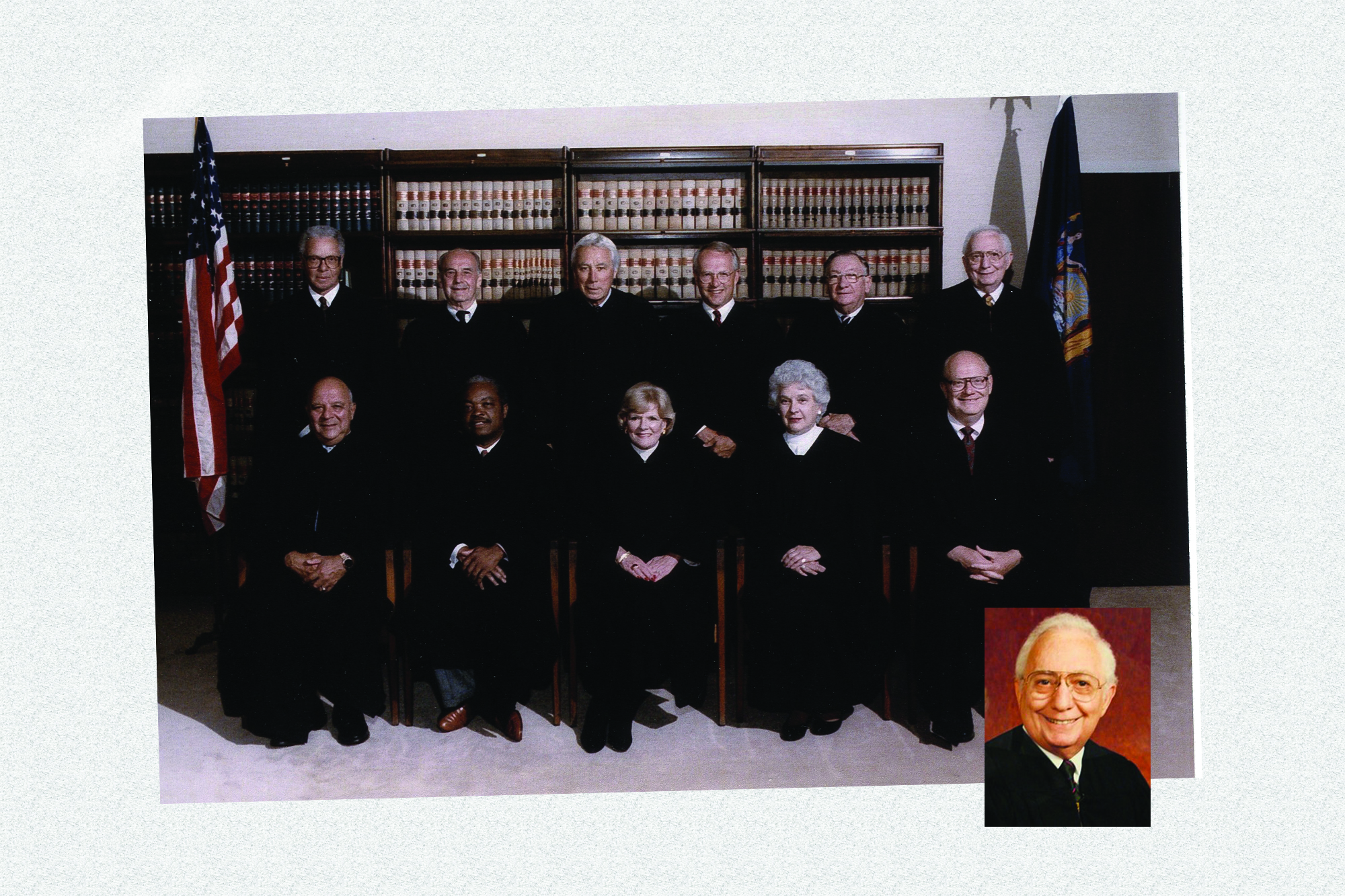

In April 1994, Governor Mario Cuomo saw fit to appoint me to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, Fourth Department. Once again I was to be Judge Boehm’s colleague; he had preceded me to the appellate division two years earlier. And it was here that I learned another invaluable lesson from my role model.

The Appellate Division at the Fourth Department consisted of eleven judges and was a very collegial body. It sat in terms; during each term, every judge of the Court came to Rochester to hear cases. When panels of the Court, comprised of five judges, conferenced a case, the other judges would be present waiting for their panel’s cases to be called by the Presiding Justice.

At conference, Dave Boehm was, as always, a model of decorum. He always listened to the views of other panel members and would state his differences, if any, in firm but considerate ways. He never demeaned another judge’s position, but he might very carefully, in his ever-so Boehm way, expose a flaw in an opposing view. Once again, a gentle soul with a powerful mind.

Early on in my time at the Fourth Department, a fellow panel member noted his disagreement with my view by stating, “Well Dick, that is really ridiculous.” I took no offense and thought the comment merely reflected the passion with which my colleague viewed the matter. Later that day, my colleague showed up at my chambers’ door with a bottle of good Scotch and two glasses. He told me that after conference Judge Boehm had approached him and pointed out that I was new and that, perhaps, I was not accustomed to the bluntness for which my colleague was known by the Court’s veterans. Judge Boehm suggested that my colleague should pay a visit to let me know he meant no disrespect. We had a drink–I confess it may have been two– and launched into a very warm “getting to know you” chat.

Judge Boehm was a man dedicated to the law and all that it requires of those who are called to serve in judgement of it. He understood that judging requires our very best effort in every case and that process – “how” we judge – is so important to preserving the law’s basic strength, which is forged in fairness. He understood that judging (particularly appellate judging) is a distinctly human endeavor and that rancor or pettiness had no place at the conference table. He was confident in the rule of law but knew the price by which that confidence was obtained.

I left the Appellate Division in January of 1997. In the ensuing 17 years on New York’s high court and then later at the Second Circuit I often think back to that day in 1976, and my time with the Judge. I hope I have continued to “Be Like Boehm.”