A Mentor for Life: R. Brooke Jackson

by Terry Fox

Select Articles (Pre-2015) | Volumes 1-98

Published August 2014

Published August 2014

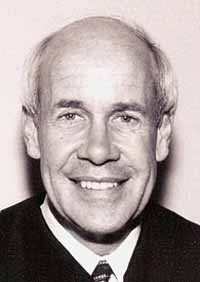

If I had to select a word to describe one of my all-time favorite and most influential mentors, fearless is my word of choice. Richard Brooke Jackson, known professionally as R. Brooke Jackson, is a United States district judge serving on the United States District Court for the District of Colorado. The United States Senate confirmed Judge Jackson on August 2, 2011, and he received his judicial commission on September 1, 2011. Before joining the federal bench, Judge Jackson served as a Colorado state trial court judge from 1998 until 2011, and as Chief Judge for Colorado’s First Judicial District from 2003 through 2011. Judge Jackson left a lucrative career at a prestigious law firm for public service because he wanted to give something back to society.

I am fortunate that I had the opportunity to work for and with Judge Jackson before he joined the bench. Before joining the state bench, Judge Jackson spent 26 years with the law firm of Holland & Hart, where I also started my legal career as an associate after spending my first year clerking for Texas Supreme Court Justice Craig Enoch, another wonderful mentor. Of course, my clerkship year was a continuation of my legal education – and possibly the best year of that education.

As an attorney, Judge Jackson was never afraid to realistically assess a case. Watching a lawyer who was completely candid with his clients – even at the risk of losing the client to a “yes-man” lawyer who would tell the client what that client wanted to hear – was an early and important lesson for me. Indeed, I recall one client who left after not hearing what he wanted to hear (only to swallow his words later, when his case ended with the precise resolution Judge Jackson predicted). This lesson followed me for the seventeen years I tried cases before I joined the Colorado Court of Appeals. I was a better lawyer, and I am the judge I am now, because of the day-to-day lessons Judge Jackson imparted upon me. Some of his lessons were explicit, others I learned just by observing him and listening to him interact in a board room and in a courtroom. I am most thankful, perhaps, that he never assumed I was less capable because I am a woman or because I am Hispanic. He judged me on my own merit and mentored me selflessly.

As a jurist, Judge Jackson has never feared making the right decision, even if it is not always a popular one. For example, he recently invalidated a local ordinance restricting where convicted sex offenders can live. Ryals v. City of Englewood, 962 F. Supp.2d 1235 (D. Colo. 2013). The ordinance barred convicted sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of any school, park or playground, or within 1,000 feet of any licensed day care center, recreation center or swimming pool. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued on behalf of a man who bought a house in the City of Englewood, but later found out he could not live there because of his sex-offender status. Plaintiff’s expert testified that the law renders approximately 99% of the City of Englewood off-limits to most sex-offenders. Id. Though rules restricting where sex offenders may live are undoubtedly popular, Judge Jackson found the ordinance invalid. According to Judge Jackson, the ordinance leaves few places for offenders to live, forcing them to live in neighboring cities. Id. at 1242. The ruling, though perhaps not “popular,” reflects Judge Jackson’s adherence to the rule of law for all individuals, regardless of whether the decision draws media attention. See Judge Overturns Englewood Sex Offender Law (AP), at http://denver.cbslocal.com/2013/08/22/judge-overturns-englewood-sex-offender-law/.

Another illustrative case occurred only a month after Judge Jackson was sworn in as a state judge. He was appointed to Colorado’s first three-judge panel to consider a death penalty case (the law was later changed to reinstate the jury’s imposition of death penalty sentences). Id. The panel unanimously rejected the death penalty for convicted murderer Robert Riggan after a sentencing hearing. Id. The decision was criticized.

Shortly after rejecting the death penalty in Riggan’s case, Judge Jackson encountered more criticism after reducing a convicted sex offender’s 10-year prison sentence to two years in jail plus 10 years of probation so that the 28-year-old man could attend therapy sessions. See Sue Lindsay, Judge in Columbine litigation used to scrutiny, controversy, Rocky Mountain News, April 26, 2000 [hyperlink no longer available]. The sentence left prosecutors and the 12-year-old victim’s father stunned, but Judge Jackson concluded that the man, who is black, partially deaf and functions at a third-grade level, needed special treatment that was not available in prison. Id. Judge Jackson said he looked down the road, after the man got out, and did not like what he saw. Id. “Given what he did, his age, his appearance, his handicaps and perhaps even his minority status, one must wonder what would emerge from the Department of Corrections in 10 years and what type of a risk to society he might present then,” Judge Jackson wrote in his sentencing opinion. Id.

Judge Jackson’s analysis upset many prosecutors, but it is completely in line with the character of the man I worked with at Holland & Hart. Id. And I’m not alone. Former Holland & Hart partner, now Colorado trial judge Bruce Jones, said that Judge Jackson’s “overriding philosophy of the law is to do the right thing.” Id. I could not agree more with Judge Jones’ assessment.

Less than two years after his state court appointment, Judge Jackson was involved in the Columbine High School shootings case. And, over the strenuous objections of the county sheriff’s office, Judge Jackson sided with the victims’ families, ordering the sheriff’s office to show them several videotapes of the incident. He then set a quick deadline for the sheriff’s office to turn over their investigative report. Id. Again, Judge Jackson showed he makes decisions consistent with his understanding of the law despite outside pressures in highly public cases.

Attorney William McClearn, who hired Jackson to join Holland & Hart said of Judge Jackson: “He was cocky when he got to Holland & Hart, and he had good reason to be . . . But as the years went along, he matured, became wiser, less quick to rush to judgment.” Id.

A Montana native, Judge Jackson received his bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth and holds a law degree from Harvard. During his years in private practice, Jackson specialized in corporate law and had little experience with criminal cases when he became a judge.

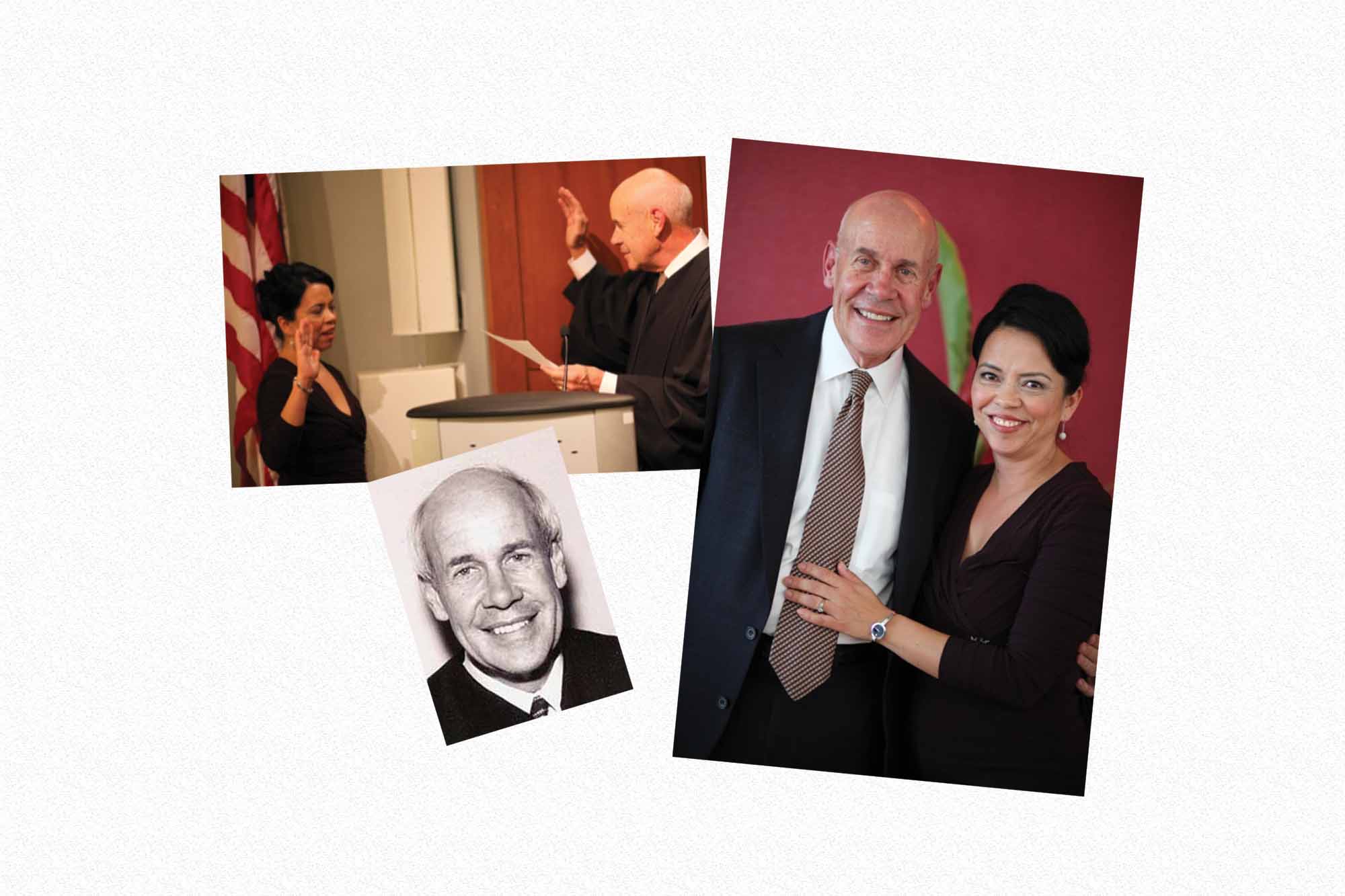

While admirably serving the state judiciary, and now the federal bench, Judge Jackson has inspired others to follow. Judge Jones, an alumnus of Holland & Hart, now serves on our state trial bench. When he was Chief of Colorado’s First Judicial District, Judge Jackson urged me to apply to the trial bench several times. He thought I could make a contribution to the trial bench, but I had my sights on the state appellate bench and he unconditionally supported me in that endeavor. In fact, he was the natural choice to swear me in when I became a judge.

I will forever be grateful for what I learned from Judge Jackson during my early legal career. I will forever be indebted to him for the example he set for me, and others, as a jurist. I am so fortunate that he has remained my mentor for more than twenty years and I have no doubt that he will remain my mentor for life. That his wife Liz is also a dear friend is just icing on the cake!

Judge Jackson and my family (below) at my January 2012 Swearing In