Designing Constitutions for a Lasting Democracy

by Elisabeth Perham and Donald L. Horowitz

Judicature International (2021-22) | An online-only publication | Download PDF Version of Article

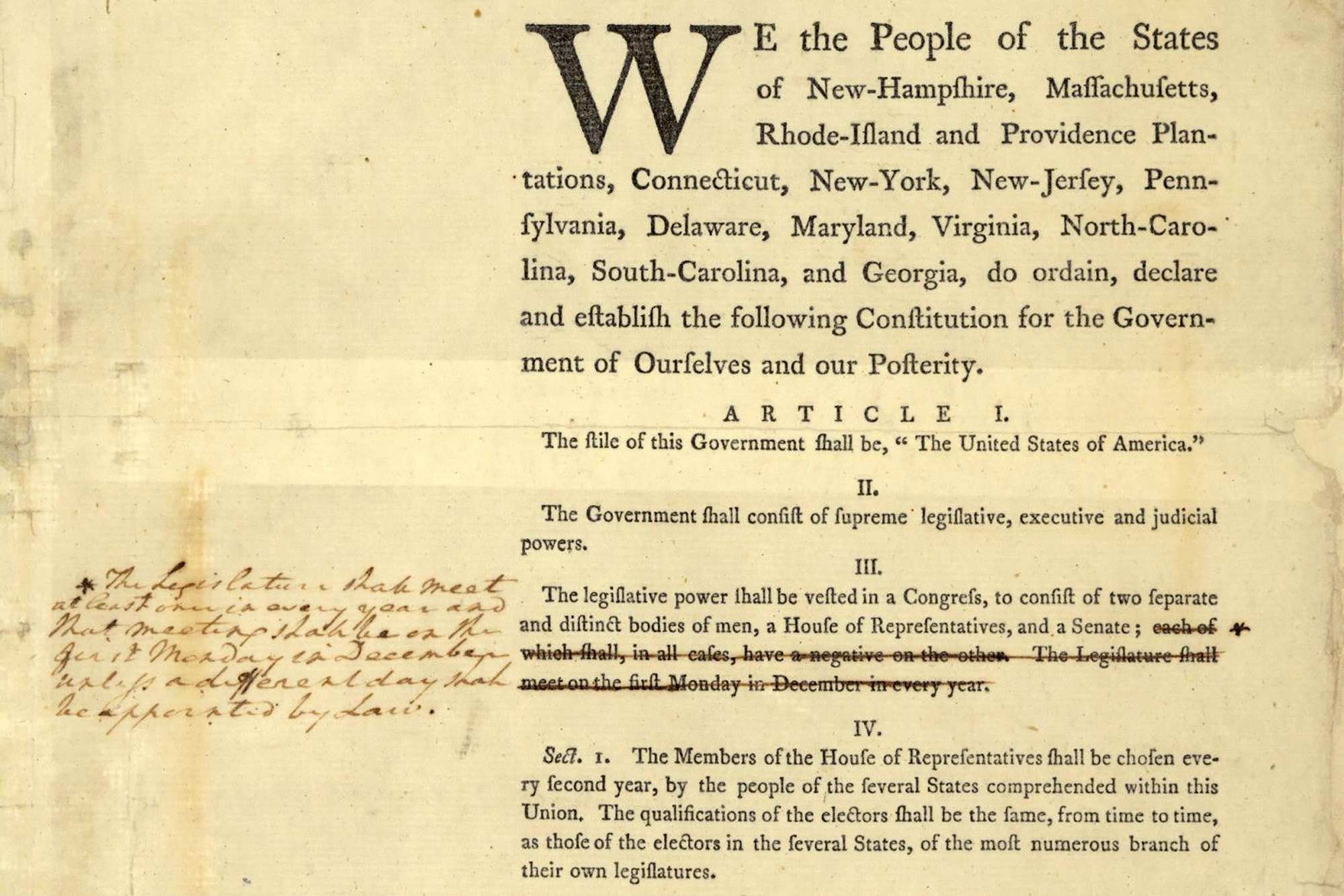

PICTURED ABOVE: GEORGE WASHINGTON’S ANNOTATED COPY OF THE CONSTITUTION (NATIONAL ARCHIVES VIA DOCSTEACH.ORG)

The rule of law in modern democratic societies generally relies upon a constitution — a founding document that reflects a society’s values and offers a framework for protecting and institutionalizing those values. Since the United States ratified the first modern-day constitution in 1787, hundreds of countries have codified their own constitutions (Cuba and Thailand are the most recent, in 2019 and 2017, respectively). Some have succeeded in building strong democracies. Some have not.

Duke Law Professor Donald L. Horowitz — the James B. Duke Professor of Law and Political Science Emeritus at Duke University and one of the world’s foremost scholars on constitution-making, particularly in highly divided societies — has observed the process of constitutional design in a variety of settings over the course of several decades. In his new book, Constitutional Processes and Democratic Commitment, he explores these processes and assesses the ways in which the design process itself affects the document’s ultimate success. Constitutions designed by consensus, he argues, tend to create the strongest commitment to democracy and therefore have the best chance of long-term success.

Elisabeth Perham of Western Sydney University School of Law recently interviewed Horowitz for the International Association of Constitutional Law blog. The following is a lightly edited transcript of their discussion, in which Horowitz shares his experiences observing and assisting in the design of constitutions around the world and explains why a process focused on building consensus produces the strongest constitutions. We share it here with permission from (and thanks to) the IACL blog.

- Watch the full interview here.

- Read more about the book on the publisher’s website.

- Hear a roundtable discussion of the book among global constitutional law scholars convened by the National University of Singapore.

Elisabeth Perham: Hello, friends of the International Association of Constitutional Law (IACL) blog. I’m Elisabeth Perham, an assistant editor for the blog, and I’m delighted to be joined today by Donald Horowitz, who among other things is the James B. Duke Professor of Law and Political Science Emeritus at Duke University, is an author of eight books, has held positions as a fellow or visiting professor, research fellow or fellow at institutions in Australia, Germany, Hungary, New Zealand, Malaysia, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and has advised a number of countries about ethnic power sharing and constitutional design, particularly for divided societies.

Welcome Professor, and congratulations on the publication of your new book, Constitutional Processes and Democratic Commitment. It’s a pleasure to read, and I found it hugely enlightening. As indicated by the title, it discusses how constitutional processes can best be designed to maximize the chances of securing an enduring commitment to democracy. To start, would you mind telling us a little bit about why you decided to write this book?

Donald Horowitz: I’d be happy to. I have, over the course of many years, seen a lot of constitutional processes upfront — beginning in a sort of accidental way in Nigeria during one of their several constitutional processes some decades ago. I happened to be in Nigeria and became a consultant to one of the delegations to the constituent assembly, which asked me to evaluate a proposal made by another delegation for an electoral system to choose a president. They were moving at the time from a parliamentary system to a presidential system and they wanted to choose a president in a way that would not be conducive to ethnic bias in the incumbent who was chosen. They actually had devised a unique way of doing it, of which I thoroughly approved. And what we did was to go over a lot of data in the course of a relatively short time to figure out how it might come out. And so I advised them to do it, and they did. A version of it has been adopted now in Indonesia and also in Kenya.

I also closely observed the Iraqi process in the early 2000s because I was a member of a U.S. government committee that was following Iraqi developments. And I was asked by people in Afghanistan to produce a memorandum in response to some memoranda that they had gotten from American academic lawyers, urging the Afghans to adopt an American system of judicial review for constitutionality. Circumstances there were very different from those prevailing in the United States, and I was happy to produce a more balanced memorandum than the one they had. And finally, just pulling out examples out of the hat, I was involved in the early stages of the Fiji constitutional process that eventuated in a new constitution of Fiji in 1997.

So I have seen a lot of constitutional processes, and how they fail and how they might succeed, and that’s what compelled me to write this book.

Perham: What did you hope to see as the book’s main contributions? And who do you see as the main audiences for this book?

Horowitz: Well, the book makes an argument for consensus decision making. If you go back and think about constitutional processes, or in fact almost any decision processes, there are several different standards by which one can make decisions. One can do it by majority vote. One can make a decision by negotiations in which reciprocity is the prevailing underlying method. Or one can look for a consensus — that is, you and I can look for a way of living together in politics that suits us both. Not because you want one thing and I want another thing, as in a negotiation; or we want the same things but different quantities of them, which is another kind of negotiation; and not because my people have outvoted your people; but because we’ve agreed to seek consensus as the method of proceeding with political life together.

I’ve always thought consensus was likely to do a better job than negotiation or voting. And we know, for example, from studies of deliberative democracy, that consensus as the standard induces people to make better arguments and to make more public-regarding arguments — that is to say, not arguments about what’s good for them, but what’s good for the collectivity. We also know the same thing from jury deliberations where the jury must be unanimous, as for the most part they must be in criminal cases in the United States. Jury studies show that better arguments are made, that minorities get their views attended to more closely and that people listen to each other better when the standard is unanimous decision making. Now, if you read the book carefully, my notion of consensus isn’t exactly the same as unanimity, but it’s pretty close to unanimity, and it ought to elicit the same kinds of good arguments. Of course, you can’t resolve everything by consensus, even in the best processes. So once in a while, you’re going to have to compromise. Once in a while, you may even be relegated to voting. But that’s what the main contribution is.

As to the audience, this is a book I think that’s not too filled with technical material, and so it ought to be able to be read by anybody who’s had a decent education, and specifically it ought to be read or can be read by students, by faculty members, and I’m hoping that it will be read by people who make constitutions and people who advise people who make constitutions.

Perham: As you’ve mentioned, you’ve spent your career working on these kinds of questions around constitution making for severely divided societies around the world. And you’ve focused both on process, as in this book, and on design questions. In the preface you say that you initially saw the questions of process and design as one single subject, but then you decided that they were, in fact, best treated separately, and this book focuses on process. Could you speak a little bit more about why you decided that process and design needed to be treated separately?

Horowitz: Well, I think the process ought to be able to travel well, regardless of what the design is going to be. Undoubtedly, the process will affect the design, but the truth is that there are many disputes about what the right design is, especially for severely divided societies, but also for all societies. Are we going to go parliamentary or presidential, for example? Are we going to go federal or unitary? These are some standard questions that sometimes plague decision makers in the course of constitutional processes, because they just don’t agree. But if they agree on a process, I think they’ll do a lot better in sorting out those disputes.

With severely divided societies, there’s a very big dispute in the literature between those who advocate a consociational regime. That’s a regime in which all groups are included — not just in the parliament or the legislature, but also in the executive branch of the government — and in which groups are said to have a veto, a suspensive veto or maybe a final veto, over policy. I find I’m not a very keen fan of that mode of constitutional design, because I think it’s conducive to a lot of stalemate because of the veto feature.

And the alternative to that is the centripetal model, which features interethnic coalitions of ethnically based parties, which are very common in severely divided societies, and those interethnic coalitions then get together to pool their votes. The only way they can do that is to behave moderately on issues of concern to all groups, and the result is an interethnic coalition that produces some satisfactions for pretty much everybody. I think that’s better. If you superimpose disputes about how to proceed — where I want a consociational regime and you want a centripetal one, and somebody else wants neither, or a straight majoritarian regime — you really won’t get anywhere. So I wanted to lay out a process that could travel, regardless of whatever the substantive disputes happen to be about or what the right dispensation is for a particular country.

By the way, I should also say that this is an argument, it’s not a proof. This question isn’t definitively settled by my book. I just wanted to push the ball down the road as great a distance as I could.

Perham: I thought one of the most powerful things in the book was the combination, in building the argument, of the theoretical insights — which you’ve drawn from, among other places, political theory and constitutional law — and empirical insights from political science presented in combination with many case studies from constitution-making processes around the world. I also appreciated the chapter-long case study, of the recent Sri Lankan process. I found the case studies very helpful, both in illustrating the points to assist in understanding what you were saying and as evidence towards your argument. I’m working on my PhD at the moment, so I know case study selection and methodology is always a vexed question in comparative work, and I wondered if you could speak a bit more about how you thought about these issues when writing the book?

Horowitz: Yes, the book takes off from a remark in another book by Tom Ginsburg, Zachary Elkins, and James Melton, The Endurance of National Constitutions (Cambridge University Press, 2009). And they say, look, with respect to process, we know one thing about it: that if all social groups are included, meaning all ethnic groups as well, or religious groups for that matter, then that’s more conducive to a durable process. And other people have shown that inclusion indeed is conducive to a more democratic outcome. So the question then is: What else makes for a good process, for a durable constitutional or democratic constitutional outcome?

And it seems to me, that’s a question very well worth pursuing, because process choices are terrifically important. And they say, well, we can’t deal with this question because, by one account, there are 18 different processes. And we can’t process the processes by using quantitative methods that are familiar to us. So there’s going to have to be a lot of digging in case studies. I said, “Well, I’ve been involved in a lot of case studies, and those I haven’t been involved in, I think I know which ones have been written up well enough so that one can extract material from them.” But what do you want? Well, we want material on those: If the hypothesis is that consensus should help, let’s get some where there was consensus, and let’s get others where there wasn’t consensus.

By the way, my idea about consensus and constitution making originally comes from Indonesia, because I observed the Indonesian process very, very closely and wrote a book called Constitutional Processes and Democracy in Indonesia, published by Cambridge Press in 2013. The Indonesians practically took no votes. They took one vote, but not on anything having to do with the constitution as such. They waited until they got a consensus. And so if that’s the beginning of the hypothesis, then along comes the Tunisian constitution of 2015, which the best write-ups say was a product of consensus supplemented by negotiation — maybe requiring one or two votes along the way — but with an overwhelmingly favorable vote at the end, which, it seems to me, supported the idea that this was a consensual document, and a consensual document involving two polarized sides: One of them was decidedly, and aggressively, and militantly secular, and the other side started out representing an Islamist party, which in the end, came to be really not an Islamist party, but an Islamic party with a democratic agenda. The two sides fought quite a lot, but in the end they mostly reached consensus. They did have a negotiation or two. In fact, one, has an ironic connection to the thesis of this book. But for the most part, they reached consensus on what they were doing.

It’s not a perfect constitution. And, as you know, there’s been a coup in Tunisia subsequently, and so you might say, “Oh, it discredits the thesis.” But actually it doesn’t, because the coup was made by somebody who was not committed because he wasn’t a member of the constitutional drafting committee. He was actually, for a time, in the expert committee that advised it, but he wasn’t really involved in the constitutional process in a deep way. He eventually became president. He came out of nowhere to be elected president. And the Islamists didn’t want a presidential system, they wanted a parliamentary system.

In any event, so along comes Tunisia, and then I said, “Gee, the Indian constitution, if I recall correctly, was made by consensus,” and indeed when I went back and looked closely at the process for the Indian constitution, it was made by consensus. Again, a few votes, and a lot of positions changed along the way. People argued. Consensus involves argumentation and reasoning in a process of deliberation, which can change people’s minds. And quite a lot of that happened in India.

So I’ve got those cases — Indonesia, Tunisia, India — on one side, and then I wanted to contrast negotiated outcomes and majoritarian outcomes, because negotiation and voting are alternative ways to make constitutions. So there we have the deals in Iraq and Kenya and Fiji, and the majoritarian constitution of Nepal that was made contrary to the earlier consensus-seeking process. So I have those four cases, which are pretty extensively examined in the book in contrast with the three consensual cases. And it turns out that the three consensual cases are not perfect democracies, but they have much better democracy scores by any objective measures than the four that were not made by consensus.

Now that’s not to rule out an endogeneity; it is possible that predispositions govern the choice of process. That’s okay, as long as we know that one process is more likely to produce a result than another. Be that as it may, that was the way I selected the cases: by which ones were well enough written up so that one could really figure out what the essence of the decision process was, and particularly those that I knew something about more intimately, as against others about which we also knew a lot but were made by a different process.

Perham: You’ve sort of spoken a little bit about the influences of working in certain countries and the Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton book, and, of course, you yourself are one of the leading scholars in the world of questions of constitution making and severely divided societies. I also wondered who else’s work was influential on you throughout the course of the project?

Horowitz: I can name a few people, actually. Jon Elster, who is a Norwegian scholar who teaches these days at Columbia University in New York, but previously taught at the University of Chicago and then the Collège de France. He is, I think, the gold standard on deliberation and constitutional processes. I don’t agree with him on everything, but he hasn’t regarded me as an enemy yet, which is a little unusual in academic life! He says, “You should avoid bad processes. We know what’s bad. We don’t really know what’s good. Just avoid what’s bad, and that’s the best we can do. And for the rest, leave the decision makers alone.” I think we can actually do a little bit better than that. I agree with him that we don’t know everything, but we do know a few things.

He also says that we shouldn’t allow legislators to make constitutions, because they will advantage themselves in their later lives. If they’re going to go back to being legislators, they will write a good constitution for the advantage of legislators. The evidence doesn’t suggest that is generally true. I can think of one or two cases where it has been true, but mostly, it’s not true — especially, by the way, if you get them onto the consensual path, because then they’re thinking about living life together in politics. That’s the way I like to think of it anyway. But I do think that his treatments of the deliberation in the American constitutional framing in the 1787 constitution and in the Estates General at the time of the French revolution are quite wonderful treatments.

A more practical person, but also an academic, is Christina Murray, who is emerita professor at University of Cape Town, now with the UN, and is one of the most experienced constitution makers in world. She was involved in South Africa and in Kenya and in a dozen others. Not only does she have good ideas, both in print and out of print, but she also corrects a lot of my errors. A lot of people who write think that they don’t have errors in what they write. I’m willing to presume that I do have them, but I can’t find them. And if you have someone who can find them for you, that’s really helpful, and she’s excellent at that.

I’ve also found, by the way, your mentor, Rosalind Dixon, is very persuasive, especially on drafting questions. And I’ve been involved in one or two sessions with Ros when she had really perceptive things to say about how we should draft this. She figures in the book about drafting long and drafting short, and her observations on that I think are quite cogent. So those are some of the people who are most influential, I would say.

Perham: I’m coming from an early career point of view, but I think this next question is interesting to, well, all of us who write. What were some of the main challenges that you faced in writing the book?

Horowitz: I can think of two kinds. One is at a certain level, trivial, but very annoying. There’s always something missing in the middle of something that you’ve written. So you write a chapter thinking that you’re going from A to Z, and you’re going A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and lo and behold, you’ go back, and it turns out that L, M, N, O, and P are missing, just because your mind skipped over those things. And going back to fill in missing pieces, I think is much harder than doing it the first time. And you do need to go back and fix it up.

But another challenge with this book, as I say, is it has an overriding argument about consensus. But there were a few other things I wanted to say — I wanted to deal with ripeness, for example. Yemen and Somalia shouldn’t have tried to make constitutions because things were too disorderly there. And in fact, the constitutional effort in Yemen only inflamed the Houthi rebellion and also the secessionists in the South, the Hiraaks in the South. So I wanted to say something about ripeness and how to handle ripeness. If it’s not ripe, I think I have a pretty good solution for that: If you have an interim constitution that is not the one you want, but it’s serviceable at least for making the new constitution, use that and stick with that for a while, until the time is ripe for making a new constitution.

Another topic that I wanted to deal with is faithless interpretation. There’s some really great cases of faithless interpretation in Malaysia, though they are now coming out of that and producing much better interpretations by a process that’s fascinating to watch. But reneging — why does the next generation renege? Well, it reneges more often, actually, with respect to bargains that it sees in retrospect as having been unfair than it does on consensus. That’s at least my working hypothesis.

Or timing. Timing in Sri Lanka was always out of joint. They started out right after a good election that was favorable to the new process, but they wasted a lot of time, including in public participation, which is another question that I also wanted to integrate into the book. I’ve always had strong views about that and how public participation was oversold — it’s not useless, but it was certainly oversold in constitutional process studies. They did waste a lot of time on public participation that only taught them something that they already knew, namely, that the public was divided on the question.

Furthermore, they had an internal problem with their experts that I didn’t emphasize very much in the chapter on Sri Lanka. Their experts disagreed with a lot of the procedures that were being used — not so much with the substance, but the procedures that were being used — and they didn’t control the experts very well, and make very good use of them. That slowed them down. By the time they were done, they had a different timing problem — namely, they were running up against an election, in which a president who had been unpopular in 2015 suddenly became popular again, and he was about to return to office. He became prime minister. He couldn’t come back as president. His brother, however, became the president, so you get the idea that it’s a family business. So then their consensus fell apart at that point, and they had to abandon the project.

Those weren’t the only problems. The major problem was that neither the president nor the prime minister at the time, who were from different parties, but had lined up for the 2015 elections, was really committed to the venture. They were both afraid of it, in a certain way. They were afraid of losing some of their clientele to what might become an unpopular venture. So they defected in advance, in a certain way.

So there were many problems. And I wanted to integrate all of these into the book, and I had to do a separate chapter on Sri Lanka. There was no way to do this short of a full engagement with Sri Lanka. The interviews were conducted either by telephone or by zoom, because by then, we were into the pandemic and there was no chance to just drop in to Sri Lanka for this purpose, quite the opposite.

So those were some of the things I wanted to include.

Perham: What’s next for you in terms of academic projects?

Horowitz: Three things, actually. I’m the co-editor of an edited volume on Malaysia’s electoral reform proposals that were put out by a commission that was assigned to do the work during the previous regime that came to power in 2018 but fell in 2020. They produced a quite complete report dealing with many aspects of electoral reform, which are long overdue in Malaysia, ranging from whether to deal with malapportionment, electoral system reform, real change in the electoral system they proposed, changes in the way the electoral commission operates, changes in the way in which legal challenges to election results proceed, and so on. So this is a kind of soup-to-nuts set of proposals, and the book tracks all of those and some others. For example, the role of civil society in producing reform proposals, which then get picked up by the commission, dealing with electoral reform.

The second project I’m nearly finished with: A book on federalism, regional autonomy, and ethnic conflict, because federalism and regional autonomy are frequently recommended to deal with ethnic conflict, sometimes with some considerable success. There are two big surprises in this book: There’s an argument that if you produce a federal regime in an ethnically divided country and there are certain units that are populated by particular groups that are minority in the country as a whole, but a majority in those units — as, for example, in Scotland, or in Catalonia, or in many other countries — you will foster a secession. But successful secessions don’t seem to eventuate from such federations. If you reason about it very carefully, and you look at the cases very closely, this is a big surprise.

The less controversial but maybe more surprising finding is that devolution to units that are inhabited by majorities, whether they are majorities in the country as a whole or majorities merely in those units, works out very, very poorly for minorities in those units. That is, there’s a tremendous amount of violence, oppression, lack of freedom, discrimination against those minorities in many, many countries that have had this kind of devolution. And it’s serious. Why is it allowed to fester? Because it’s a rule of law problem, because most countries haven’t figured out how to cope with discrimination. They haven’t figured out, effectively, how to produce legal remedies for discrimination and how, for that matter, to produce police who don’t discriminate when there’s violence. This problem is pervasive. I’m still documenting it. And I will come to some suggestions, not for how to adopt a rule of law where there isn’t one but how to shore up the rule of law where there are rudiments of the rule of law but they’re not being effectively utilized.

In the meantime, I’ve got another book that I’ve been working on for years, a big comparative book on power sharing in ethnically divided countries and why it’s so hard to do. Power sharing is a big adoption problem, because majorities want majority rule, and minorities want freedom from majority rule. I wrote a brief piece in the Journal of Democracy in 2014 on this very question, but this book is going to be a long book. That’s one reason why I decided that I had to write the process book separately and definitely not incorporate that in it.

I’ll tell you something funny: My book Ethnic Groups in Conflict is an exceedingly well-cited book, but mostly I think by people who haven’t read it, because they say, “I’m looking for a citation where it says such-and-such is the case in an ethnically divided country.” And they say, “Well, Horowitz has 684 pages, it must be in there, so I’ll cite that.” So yes, frequently cited books have two different sides. One, they’re influential on the merits and therefore they’re cited. Or two, they’re presumed to be compendious, and therefore they’re cited. And I’ve always been afraid that Ethnic Groups in Conflict is cited because it’s presumed to be compendious!

Perham: Thank you so much, Professor Horowitz, for your time, and to our listeners and viewers on the IACL blog for joining us, today or into the future.

Horowitz: My pleasure. Thank you.